Why Marvel and DC Should Be Making Superhero Webcomics

Over the past several years, attracting new readers to comics has become the most important question that mainstream super-hero genre has to face. Sales numbers have been falling across the board for quite some time, and DC Comics has even taken the drastic measure of relaunching their entire line with over fifty brand-new first issues in hopes of luring in the readers that they aren't getting today.

But here's the thing: While the super-heroes of the printed page are suffering, there are millions of people in the world reading, loving and supporting comics on the web every day, while the #1 monthly superhero comic barely cracks 100,000 -- if it's lucky. So with that in mind, why aren't DC and Marvel producing webcomics? And the more I think about it, the more it seems like it could be a pretty easy experiment to test out, with almost no risk and the potential for a huge payoff.As for why it hasn't happened before, I'm not sure, but I've got a pretty good guess. I think a lot of it has to do with people making comic books still regarding the Internet as a market that's completely secondary to -- and completely separate from -- printed comics. That may very well have been true at one time, and even fairly recently [Editor's note: yup] but it certainly isn't anymore. Just look at the numbers.

According to ICV2's sales charts, the top-selling comic for May (Fear Itself #1) sold just under 130,000 copies, which, for today's monthly singles market, is an unqualified success. Meanwhile, Penny Arcade is getting two million hits per day.

Obviously, those are two hugely different comics. They're in different formats and they appeal to different audiences, with Penny Arcade aimed at the video game market rather than the super-hero market (such as it is). But the most crucial difference is that Penny Arcade is free. You can click that link above and go peruse the entire thing from beginning to end and it won't cost you a cent. But while it costs you nothing to read that comic, it's turned out to be a pretty profitable enterprise for its creators, to the point where it's allowed them to not only make it their full-time job, but create a sprawling media empire involving the creation of charities and huge conventions.

Obviously, those are two hugely different comics. They're in different formats and they appeal to different audiences, with Penny Arcade aimed at the video game market rather than the super-hero market (such as it is). But the most crucial difference is that Penny Arcade is free. You can click that link above and go peruse the entire thing from beginning to end and it won't cost you a cent. But while it costs you nothing to read that comic, it's turned out to be a pretty profitable enterprise for its creators, to the point where it's allowed them to not only make it their full-time job, but create a sprawling media empire involving the creation of charities and huge conventions.

Of course, Penny Arcade is a complete and utter anomaly that's a thousand times better than any best-case scenario for the premise of "two guys make jokes about how long load times are for PC games." But for our purposes today, none of that really matters.

What matters is the number: two million people -- almost 20 times the number of people who bought the highest-selling super-hero comic on the stands -- and while it might just be a three-panel gag strip, they're already reading comics. This is Point One.

In fact, if there's any indication to be found in the number of times a Penny Arcade strip (or a Shortpacked strip, or a Dinosaur Comics strip) about mainstream super-heroes (okay, let's be honest, about Batman) gets spread around, posted on forums or emailed to your friendly neighborhood Batmanologist, I think it's also pretty safe to say that a large number of these readers are already aware of and like reading stories about mainstream super-heroes.

I mean, really, I'm just going on the fact that the punchline crops up in every single Internet conversation about the character, but I'm willing to bet that the most-read Batman story of the past ten years isn't Hush, it's probably this strip from Scott Kurtz's PVP:

You can even take it a step further: There are entire comics out there, like our pals at Let's Be Friends Again, that are doing quite well that are based on awareness and affection for those characters. Again, there's an obvious difference between these strips and the "official" comics in that the web versions are parodies that often involve a quick punchline, but the fact remains that they only exist and succeed because there are people -- most of whom are not reading mainstream super-hero books -- that are reading comics with these characters. This is Point Two.

So why hasn't there been an attempt to bring these two points together and lead that massive audience to super-hero comics?

To be fair, DC and Marvel have both made attempts at capitalizing on the webcomics market before. DC ran Zuda, a webcomics imprint that focused on original franchises from new creators, for three years, and Marvel's Digital Comics Unlimited service has actually gone a step further by creating original digital content set in the Marvel Universe, although not much of it. But neither one of those initiatives are what we think of when we think "webcomics."

Marvel and DC should do away with the clunky flash interfaces and any sort of paywall and create webcomics in the same format and interface that's used by Achewood or Dr. McNinja. They should use their existing characters that have decades of popularity and brand recognition. And -- this is the key part -- they should make those webcomics "count" by actually setting them in the DC or Marvel Universes.

Marvel and DC should do away with the clunky flash interfaces and any sort of paywall and create webcomics in the same format and interface that's used by Achewood or Dr. McNinja. They should use their existing characters that have decades of popularity and brand recognition. And -- this is the key part -- they should make those webcomics "count" by actually setting them in the DC or Marvel Universes.

In other words, create a webcomic starring one of their popular characters that's treated like any other comic they produce, except deliver it to readers on the web, for free, in stories meant to be read a page at a time. Keep the story accessible enough to draw in new readers, but reference the printed comics in the same style as the footnotes in old comics sending readers to the printed stories while doing the same thing there to send print readers to the web. Make the webcomic as important and valid as the other stories, right down to putting a top-notch creative team on it.

It might seem like a tall order to just start producing stories that are both easily accessible and able to drive readers to a larger universe, but, well, super-hero comics did exactly that for about forty years. I'm pretty sure someone could figure it out.

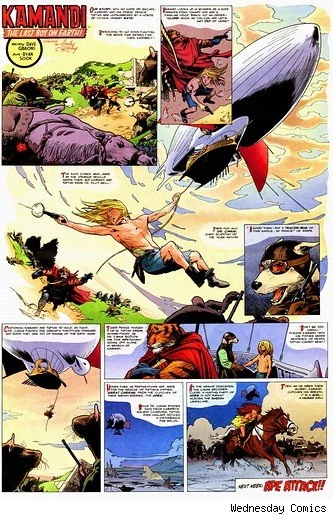

There might be some hiccups in figuring out how to write for the web rather than for single-issue comics, but I doubt it'd be that much more of a challenge than going from 22 pages per issue to 20. And just to keep things in perspective, two years ago DC put out Wednesday Comics, a bunch of giant 12-page stories that were released one page at a time on a weekly basis. The only difference between that and doing a webcomic is that Wednesday Comics was out of continuity and meant to capitalize on the grandeur of the old-timey newspaper page, something no one who is alive right now actually has any nostalgia for. If they could take that risk, I don't see a reason why they couldn't take this one.

Because really, if, for example, DC launched Batman: The Caped Crusader as a webcomic on DCComics.com (with a dedicated URL redirecting to it), I have to imagine that a good portion of the existing comics' audience would at least give it a shot, and I'm pretty sure that the webcomics readers who like the idea of Batman but don't actually want to pay to read his adventures on a monthly basis would be right there with them.

But that leads to what's probably the biggest hurdle for the people in charge, namely the idea that if you're giving something away, you're not making any money off of it. That's certainly true for a lot of webcomics, but in this case, I think it would work out a little differently. If you're an unknown artist doing a webcomic on your own with a character you created that no one's ever heard of, then you have to build your audience form the ground up. But characters like Batman and Spider-Man already have 60,000 people reading their adventures every month -- and those are just the people willing to buy the comics.

Batman alone is a character that's been popular for seventy years, with seven movies and five television shows' worth of time becoming someone the general public is pretty well aware of. Right off the bat there's a huge potential audience, which leads to the first and most obvious way of monetizing it: advertising. Heck, you can even advertise your own stuff. Why bother with just a footnote to Strange Apparitions or Kraven's Last Hunt when you can drop a link to Amazon, Comixology, Midtown or Things From Another World right there alongside the page?

Batman alone is a character that's been popular for seventy years, with seven movies and five television shows' worth of time becoming someone the general public is pretty well aware of. Right off the bat there's a huge potential audience, which leads to the first and most obvious way of monetizing it: advertising. Heck, you can even advertise your own stuff. Why bother with just a footnote to Strange Apparitions or Kraven's Last Hunt when you can drop a link to Amazon, Comixology, Midtown or Things From Another World right there alongside the page?

Second, and more in line with the current comics market, there's the fact that like every other comic, it could be collected and released in paperback. A Mon/Wed/Fri strip produces around 150 pages a year, the perfect amount to collect and release to comic book stores and bookstores. In fact, that's exactly the model being used by companies like Top Shelf, who released the entirety of Paul Tobin and Colleen Coover's Gingerbread Girl online as a webcomic before printing up the collection last month. But with super-heroes, you have the added bonus of releasing what's meant to be an accessible story with your popular characters (many of whom are featured in movies) to a larger market.

Third, and most importantly, so what if it doesn't make any money? After all, the idea here isnt to make something new that's going to be profitable, but to make the existing books more profitable by increasing readership, drawing them in with the webcomic to foster a love of and direct them to the main line titles. In essence, it's all marketing for the other titles, with the potential of reaching millions of new readers. And if even ten thousand -- a fraction of what comics like Dr. McNinja, Shortpacked and others get -- follow from the web to the existing comics, that's a pretty significant change.

Obviously, there's the chance that I'm completely wrong about this and that releasing a high-profile, in-continuity webcomic would have absolutely no impact on the other titles. But again, so what? DC and Marvel already have websites set up, so it's not like experimenting with this idea would add a noticeable amount to their traffic costs. And let's be real here: if Warner Bros. and Disney can't handle an extra hundred thousand hits, they have severe problems they need to take up with their IT department.

Even if it was a catastrophic, worst-case-scenario failure, the only thing they lose is the creative team's page rate and whatever they pay someone to set up the comic -- and if they want to go on the cheap, I can assure you that they can knock that part out on a Friday afternoon. Without collecting it, there's literally no additional cost, and there's no way that's not far less of a risk than releasing a new mini-series or, say, releasing 52 all-new comics at once.

There's nothing to lose and the potential of literally millions of new readers to gain. So why not?

More From ComicsAlliance

![Five Stars: Starting At The End With Jeff Smith [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/FiveStars-Smith.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Take Me to Your Teacher: Trevor Mueller and Gabo Discuss ‘Albert the Alien’ [Webcomic Q&A]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/0ALBERTVOL3_COVER_notitle-copy.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![‘Runaways’ Meets ‘Coraline’ in Cait May and Trevor Bream’s ‘Irregular’ [Webcomic Q&A]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Irregular_Banner.jpg?w=980&q=75)