J. Michael Straczynski: ‘I Would Have Absolutely Zero Right To Complain’ About Unauthorized ‘Babylon 5′ Prequels

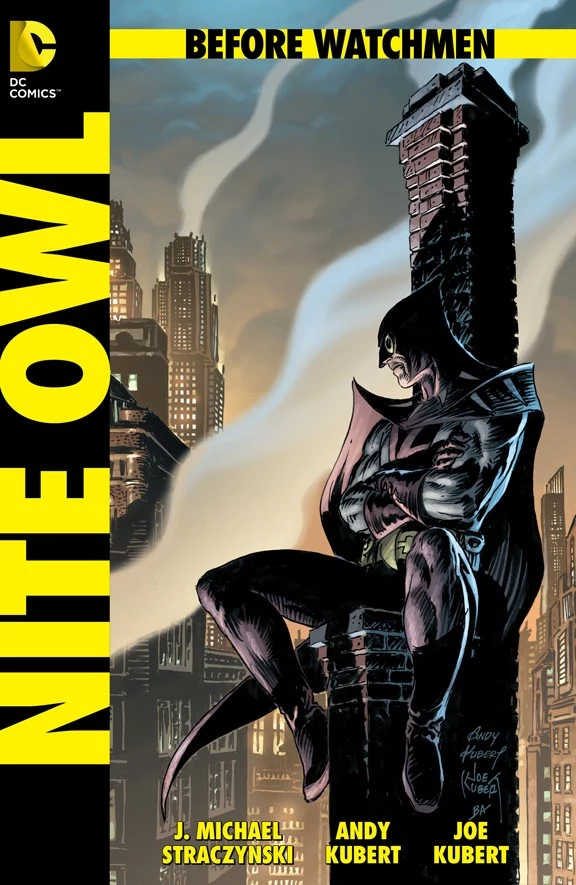

J. Michael Straczynski was the most outspoken participant in yesterday's press tour of DC Comics' controversial new initiative, Before Watchmen, whereby JMS and a host of other high profile talents will create new prequel miniseries based on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen. Owned completely by DC, the classic 1987 graphic novel about outlaw superheroes in an alternate American history is considered by many to be unimpeachable. The dominant discussion in the media and among many pros and fans is that its characters and settings are being exploited by the publisher against the wishes of Moore (but with the blessings of Gibbons). As such, Straczynski offered his own rationalization for proceeding with the work, saying, "A lot of folks feel that these characters shouldn't be touched by anyone other than Alan, and while that's absolutely understandable on an emotional level, it's deeply flawed on a logical level."

In response to Straczynski's remarks, ComicsAlliance readers as well as practically everyone else on the Internet wondered whether JMS would feel aggrieved if the tables were turned and Warner Bros. created unauthorized prequels to his own fan-favorite television saga, Babylon 5, which is owned by WB. Taking to his Facebook page (and establishing a number of caveats), Straczynski ultimately concluded that if he were in Moore's position with respect to Babylon 5, he "would have absolutely zero right to complain about it."The prevailing concern within the comics community is Moore and Gibbons' authorial control over the work and the literary implications of other creators revisiting it, but legally neither Moore nor Gibbons enjoys any control over Watchmen, a consequence of what Moore described to The New York Times yesterday as "draconian contracts" signed in the late 1980s. Per the terms of the contract, Moore and Gibbons were to be granted the rights to Watchmen after DC's edition of the book went out of print (approximately one year later), but the work proved to be so popular that the publisher has kept it available ever since.

Nearly every creator involved in Before Watchmen felt the need to comment on the ethics of the project, but no participant had more to say than the famously loquacious Straczynski, who made his views plain in a lengthy discussion with The Hollywood Reporter:

The perception that these characters shouldn't be touched by anyone other than Alan is both absolutely understandable and deeply flawed. As good as these characters are – and they are very good indeed – one could make the argument, based on durability and recognition, that Superman is the greatest comics character ever created. But I don't hear Alan or anyone else suggesting that no one other than Shuster and Siegel should have been allowed to write Superman. Certainly Alan himself did this when he was brought on to write Swamp Thing, a seminal comics character created by Len Wein.

Leaving aside the fact that the Watchmen characters were variations on pre-existing characters created for the Charleton Comics universe, it should be pointed out that Alan has spent most of the last decade writing very good stories about characters created by other writers, including Alice (from Alice in Wonderland), Dorothy (from Wizard of Oz), Wendy (from Peter Pan), as well as Captain Nemo, the Invisible Man, Jeyll and Hyde, and Professor Moriarty (used in the successful League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). I think one loses a little of the moral high ground to say, "I can write characters created by Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle and Frank Baum, but it's wrong for anyone else to write my characters."

JMS' remarks inspired many to ask whether he would feel the same way if his own most famous work, the science fiction television series Babylon 5, was given the Before Watchmen treatment. The writer acknowledged in a Facebook posting that it was "a fair question" and, limiting his response to what he called the "emotional" aspect and "not the legal stuff - that seems pretty cut and dry," the writer put forth a hypothetical scenario in which he found himself in something approaching Alan Moore's place but one in which he reacts much differently than the Watchmen author.

JMS' remarks inspired many to ask whether he would feel the same way if his own most famous work, the science fiction television series Babylon 5, was given the Before Watchmen treatment. The writer acknowledged in a Facebook posting that it was "a fair question" and, limiting his response to what he called the "emotional" aspect and "not the legal stuff - that seems pretty cut and dry," the writer put forth a hypothetical scenario in which he found himself in something approaching Alan Moore's place but one in which he reacts much differently than the Watchmen author.

How would I feel if Babylon 5 were being made and I were shut out of anything to do with it, despite my desire to be involved? I'd feel pretty crummy about it. But as it happens, that has absolutely nothing to do with this situation in any way, manner, shape or form.

If at any point in the last 25 years, Alan had said, "you know, there's a Watchmen story I'd like to tell," there's no question that DC would have given him both the freedom to tell that story and a check big enough to dim the lights at their offices for a week. And there were frequent overtures for him to do just that. In 2005, DC actually offered to give him ownership of the characters if he'd come back to do more stories with them.

Moore confirmed something to that effect in a recent interview, saying, "They offered me the rights to Watchmen back, if I would agree to some dopey prequels and sequels. So I just told them that if they said that 10 years ago, when I asked them for that, then yeah it might have worked. But these days I don't want Watchmen back. Certainly, I don't want it back under those kinds of terms."

Straczynski continued:

They wanted his involvement, solicited his involvement, would have been thrilled at his involvement. He declined at every point. Fair enough. It's his choice, and it's his right to make it.

So now – apples to apples – let's make the B5 comparison. Let's say Warner Bros. came to me and said, "we want to do more Babylon 5, and we want you to run the whole thing. We'll pay you anything you want, give you a proper budget, and you will have complete creative freedom." (Actually, they made that offer last year, and I said yes enthusiastically, because I love these characters and that universe. At the eleventh hour the distribution system they had been trying to put together fell apart, and so did this, but let's stick to the subject, shall we?)

So let's say that Warners makes that offer, and I said, "No, I don't want it, take your accursed money, your big budget and your complete creative freedom and begone, get thee behind me Satan!" Let's say they came back and said "Okay, then how about we pay you vast sums of money just to consult? How about that?"

"No," let's say I cried, "no, no, a thousand times no."

"How about just to meet with us? Just for an hour?"

"No, absolutely not, nuh-uh, no way, not a chance."

"What if we sweeten the deal? What if we offer to give you full ownership of Babylon 5, legally and contractually, so you own it? How about that?"

"Fie, I tell you, fie!"

Well, where does that leave us?

If Warners offered me creative freedom, money and a budget to do the show the way I wanted, up to and including my completely owning the show, and I said no to that deal, and if after Warners waited TWENTY FIVE YEARS for me to change my mind they finally decided to go ahead and make B5 without me...then I would have absolutely zero right to complain about it. Because it was my choice to remove myself from the process, it wasn't something foisted upon me by anybody else.

Notably, Straczynski's hypothetical does not include a contract dispute analogous to that endured by Moore and Gibbons, who believed they would receive ownership of their work as a matter of course.

Another dimension of the Before Watchmen debate is the apparent disconnect observed by many pundits and readers between Moore's objections to Watchmen spin-offs by other creators and his own prodigious work with other writers' characters. Such books include The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen -- in which figures from Victorian era literature like Captain Nemo and Mina Harker team-up on various adventures around the world -- and Lost Girls, in which characters from The Wizard of Oz, Peter Pan and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland trade sexually explicit stories from their pasts.

Another dimension of the Before Watchmen debate is the apparent disconnect observed by many pundits and readers between Moore's objections to Watchmen spin-offs by other creators and his own prodigious work with other writers' characters. Such books include The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen -- in which figures from Victorian era literature like Captain Nemo and Mina Harker team-up on various adventures around the world -- and Lost Girls, in which characters from The Wizard of Oz, Peter Pan and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland trade sexually explicit stories from their pasts.

Straczynski invoked this argument in his discussion of the "sacredness" of Moore and Gibbons' Watchmen characters:

Some folks have replied to this with "well, Alan says this is different because he's using those characters in different situations." (I'm not vouching that Alan said that, only that this is the most common reply. If he never said anything to that effect I'm happy to be corrected.)

I'm really good with the English language, but I've turned that sentence over several times and I can't parse it in any logical way. What the heck does it even mean? The moment you have Mr. Hyde do anything not in Robert Louis Stevenson's book, it's a "different situation." I think that the argument being made here is that by putting Mr. Hyde in a modern context, then that makes it Alan's and that makes it legally and morally okay.

If that's true, then I invite Alan to try that with James Bond, or Jason Bourne, or any other character where the writer or the estate is still around to fight for the rights of their characters. Legally, yes, you can do what you wish with public domain characters. But one ends up on a slippery moral slope to say that all of these other writers' characters are fair game but Alan's characters are sacred on a moral or emotional basis.

I would suggest that there are just as many people around the world who hold Wendy from Peter Pan sacred, or who might think it untoward that Alan had Mr. Hyde literally sodomize the Invisible Man TO DEATH after the latter serially raped a bunch of girls at a private school. How would Robert Louis Stevenson or H.G. Wells have viewed such a story?

Despite this, somehow, by Alan's lights, that's not just okay, it is right and proper. I'm not saying he shouldn't have done it. Alan's a genius, and if it were in my power I'd set him up with a big distribution system, ten million dollars, and publish anything he wrote, up to and including the phone book.

I'm just suggesting that one needs to be consistent in one's moral stance if one wishes that moral stance to be taken seriously.

Ethics aside, the main literary criticism that's been directed at Stracynzski and his Before Watchmen colleagues comes from the belief that Moore and Gibbons' characters were intended to and should be limited to the scope of the original and most hallowed Watchmen graphic novel, and nothing (or at least, little) else. JMS addressed that perception head-on:

A really good point whose only problem is that it's not actually true. That was certainly never DC's perception of the characters, and Alan himself floated an idea about doing a Minutemen prequel back in 1985.

Alan didn't walk away from Watchmen for artistic reasons, he walked away over contract language regarding ownership issues. It was a contract dispute. In time that morphed into something else, but that was not what happened at the time.

It should be noted that JMS' assertion is at odds with certain remarks made by Moore and Gibbons both then and now. In a statement published this week at DC's The Source blog, Gibbons said, "The original series of Watchmen is the complete story that Alan Moore and I wanted to tell."

Additionally, in 1986 Moore and Gibbons appeared at London's London's UK Comic Art Convention, on a panel moderated by Neil Gaiman, in which they specifically addressed the nature of their agreement with DC as well as their intentions for Watchmen's life beyond its initial form. The discussion was transcribed by The Comics Journal, and an excerpt has been making the rounds on various blogs as part of the Before Watchmen hoopla. The brief exchange would seem to put to put into perspective a number of dimensions discussed above:

From the audience: Do you actually own Watchmen?

Alan Moore: My understanding is that when Watchmen is finished and DC have not used the characters for a year, they're ours.

Dave Gibbons: They pay us a substantial amount of money...

Moore: ... to retain the rights. So basically they're not ours, but if DC is working with the characters in our interests then they might as well be. On the other hand, if the characters have outlived their natural life span and DC doesn't want to do anything with them, then after a year we've got them and we can do what we want with them, which I'm perfectly happy with.

Gibbons: What would be horrendous, and DC could legally do it, would be to have Rorschach crossing over with Batman or something like that, but I've got enough faith in them that I don't think they'd do that. I think because of the unique team they couldn't get anybody else to take it over to do Watchmen II or anything else like that, and we've certainly got no plans to do Watchmen II.

More From ComicsAlliance