Stan Sakai Is Proof That Lettering Can, and Should, Be Treated As Art

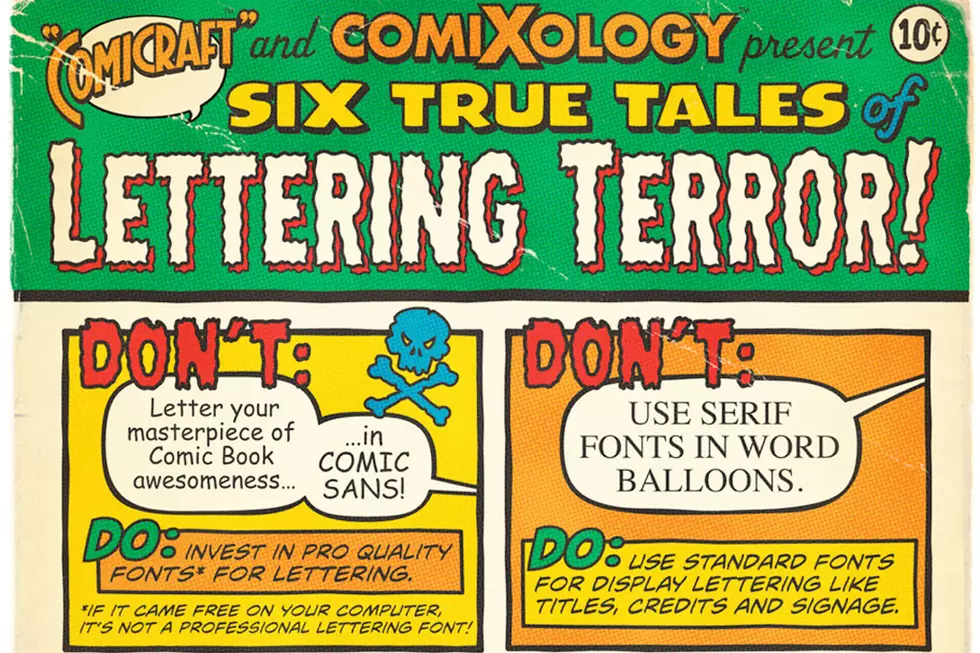

The bulk of lettering in mainstream comics is meant to be invisible. By invisible I don't mean you can't see it; it's more that you don't notice it. In the '90s, Marvel tipped too far in one direction and gave a bunch of characters distinctive word balloons: Iceman spoke in icy bubbles, the Human Torch in flame balloons. It was silly and off-putting. The status quo now is the opposite; most mainstream comics go for a uniform approach where everyone but Deadpool gets the same balloons, and the most interesting things get is caption boxes in interesting colors.

This method isn't a failure, exactly, so much as it is a missed opportunity. Lettering is horribly undervalued in comics, but it has a lot of potential, and when you trip over a comic with great lettering, it really changes how you read. It makes things better, and Stan Sakai's Usagi Yojimbo #144 is a good example of what I mean.In addition to being a good ol' story and history lesson, this issue is one of those comics that makes you realize just how much lettering can add to a comic. Sakai's a master at lettering, with a style that's both distinct and inventive. He knows when to let his lettering be invisible, so it doesn't distract you from your reading experience, and how to use his lettering to hint at something that'll subtly influence how you read his comics.

Sakai doesn't go wild with the letterforms or balloon shapes. He keeps things very simple, and in doing so, gives us space to fill in the blanks with our own thoughts and prejudices. Part of what's so interesting about lettering is how a tiny change can convey a lot. Take a look at this panel from Usagi 144:

It's very simple: A guy finds a tokage lizard lurking around a few barrels. But the difference in their word balloons is fascinating. We're accustomed to circular speech bubbles in comics. They look like regular speech, so we "hear" them as normal speech. But the tokage's balloon is square, and the letters of his "EEP!" are rendered differently than the man's "Wh-who's there?!" It looks different, so it must sound different. That's a decision our minds make on the fly, unconsciously, but examining how we interpret those sorts of decisions can tell us a lot about the art of lettering.

What does it sound like to you? To me, it sounds sharp, and a little scratchy. A normal voice sounds, well, normal. There's a little bit of musicality, and it basically just sounds like a voice. The squared off word balloon and stiffer letters make the tokage's vocalization sound distinct from a human voice, and give it a sharper tone.

One very tiny and almost immaterial thing I love about comic books is the punctuation-free word balloon. It's something that too few comics creators utilize these days. "Oof." has a different impact on your brain than "oof" does. Exclamation points represent excitement. Periods convey a flat tone. Therefore, a lack of punctuation has a sound and import all its own. It should be a tool in the toolbox, rather than an exception.

The exclamation point, as seen in this panel, has long been used as an indicator of surprise. "What are you doing here?" is much, much different from "What are you doing here?!" The exclamation point on its own, though, is something I generally only see in Hideo Kojima's Metal Gear Solid series. It still represents surprise, and has an extremely stressful sound effect to go along with it whenever it appears. But what does it sound like when you read it?

The answer, I think, is that it sounds like whatever you personally think a gasp of surprise sounds like. I used to know a guy who would -- and this is not a lie, even though it sounds like one -- literally say "yikes!" when he was surprised. That's probably what he'd hear if he read this. For me, it's the sound of a sharp intake of breath through the nose with the mouth closed. For others, maybe it's a brief gasp with the mouth open. It varies from person to person, and by giving us room to interpret, Sakai involves us personally in his story. We own these little bits and pieces, and that makes the comic partially "ours" as we read. We know what "!" sounds like.

One technique that Brian Michael Bendis, among others, uses in his comics are static panels to show a reaction or rhythm. They're often free of dialogue, too. The reason for them is pacing. It makes the reader slow down and take in the scene, or allows the writer to control the flow of the story to an even greater degree than normal. Sakai employs a similar technique in the second panel in this excerpt, but via lettering, rather than a statted panel:

The brief ">sip!<" stood out when I first read it. By this point, I was looking to see what magic tricks Sakai was using over the course of the issue, but this still gave me pause. It's elegant, and the deeper you dive into it, the more meaning it holds. The exclamation point makes the sip into a fast-paced action. The man is taking a brief taste of the drink. Without the exclamation point, meaning the sound effect would be rendered as ">sip<", I'd assume that he was taking a longer sip. As-is, I have the mental image of him tilting the cup up and then down almost immediately.

The placement of that balloon is significant, too. It comes not just after his discussion of the inferior soy sauce, but markedly after. It gets a balloon all to itself. That means that it's a separate, but related, action to his previous sentence. That creates a sense of time passing during this panel. Sakai chose to render the point in time when the man sipped from the cup, but the panel actually covers several moments before that specific point in time, too.

In this excerpt, Usagi and the man are both struck by surprise at the same moment, and share an exclamation point. They're obviously not making the same noise, but they are making the same class of noise. What that sounds like is up to us. We decide whether they're just like ours, identical to each other, or two entirely different sounds on the fly. There's no conscious thought here, just instinct.

The scream, of course, is another matter entirely. We're used to spiky or shaky word balloons to show duress or excitement, so I imagine that we all think this one sounds pretty bloodcurdling. Sakai renders this scream as all vowel sounds, and something that would warble and shake right down to your soul.

What does death sound like? I love these little skull balloons that Sakai uses whenever someone dies. They're part sound effect and part storytelling device. It's an indicator that someone has died, but it doesn't necessarily represent a real sound. I think of it as the soul leaving the body, or a dying breath, due in part to the wiggly tail on the balloon. It wobbles and wafts around, like a ghost, or a sigh. The dog here has just died in the arms of his master.

Part of what sent me down this route of looking really closely at a generally underappreciated aspect of comics was thinking about the use of punctuation, bolded words, and other effects in sound effects and dialogue. Bolded words can be used for emphasis or for rhythmic purposes. Some writers use them to show which words are accented in a sentence, while others use them to for effect. Take a look at Dave Gibbons's lettering here from the final chapter of Watchmen, from a script by Alan Moore:

Ozymandias is mocking Dan Dreiberg. You can tell it from the bolded words. Do. Serial. Masterstroke. Outcome. Each of those words holds a slightly different meaning than usual when bolded in this context. He's not just saying these words real hard. He's emphasizing "do" because the proper tense is "done." He's emphasizing "serial" because the very idea of supervillains is ridiculous and out of date. He's emphasizing "masterstroke" because he thinks he's solved everything, and he's emphasizing "outcome" because that's all that matters: the outcome. Ozymandias is arrogant and he views getting his way as an inevitability. That's why, when he's revealing that he's already won, there's no emphasis at all. Ozymandias is speaking in a flat voice when he says, "I did it thirty-five minutes ago." He's not excited. He's not shouting. It's a foregone conclusion, so why get your blood pressure up?

Bold words in comics have a bad rep. They're used for emphasis, but I regularly see people remarking that "no one talks like that!" Depending on who's utilizing this technique, though, it can work pretty well. It gives Frank Miller's dialogue a specifically pulpy pattern, and here, Sakai uses it for genuine emphasis. On top of that, he varies the size of the letters, just to set them apart from normal speech. There's no mistaking Sakai's intent in the panel above, and there's no mistaking the tiger's anger, either.

When you start varying the punctuation used, things get even more complicated and evocative. "ugh" isn't "ugh!", not by any means, just like "welp." and "welp" feel different. Periods lend a sense of finality to the word, while a lack of punctuation feels empty and open.

I like Sakai's grunts and shouts because he uses ones with lots of vowel sounds and hard stops. Case in point, the excerpt here. "GYAHHH!" is a real shout, a genuine yell, and the exclamation point gets across the urgency and effort the swordsman is displaying. On the other hand, the "GURK?!" is a beautiful thing. This character's neck has been opened by his ally, and his exclamation has a hard stop with the K sound. It's very abrupt and final, but the interrobang at the end shows you his surprise without you even having to look at the expression on his face.

These are just a few out of context panels from one issue of one long-running series. Other comics have different gimmicks, styles, and techniques. Lettering is one of those things that, once you start paying attention to it, you'll find it hard to stop. You'll start realizing who it is who enhances a comic, who's not very good, and who does so well that you never even notice that they're doing something amazing. You'll be able to pick out a comic's publisher just by looking at the lettering, deeply appreciate things like Amazing Spider-Man: Shed and Dave Sim's work.

And if you're like me, with handwriting isn't so much writing as it is eldritch runes indecipherable to the eyes of modern man, you'll hear that Emi Lenox, of Emitown fame, actually hand-lettered both of her 400 page graphic novels and take a step back in stunned disbelief.

When lettering is done right, it can add so much to a work. Next time you're reading a comic that you really enjoy, finish it up, bask in its glory, and then take another spin through its pages, this time paying close attention to the lettering. Try to figure out why it works and what it adds to your reading experience.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Enter A World Of (Tiny) Magic With The ‘Masters Of The Universe Mini-Comic Collection’ [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2015/09/MOTU00.jpg?w=980&q=75)