Away From Human Memory: Editing And Composition In Frank Miller’s ‘The Dark Knight Returns’

Recently I read Miguel Corti's experimental comic Watchmen #13. A cut-up pdf created by numbering and randomizing the panels in Alan Moore and David Gibbon's Watchmen, the book is laid out along variations of the original's consistent nine-panel grid. It is a compelling read, one that made me think about the other major superhero comic of the same era. Another book that pursues it's narrative through a strict system of grids.

Created in 1986, Frank Miller's four-issue miniseries, The Dark Knight Returns, is considered a classic of the superhero genre and of the comics medium in general. Inked by Klaus Janson and colored by Lynn Varley, it is not my favorite by Miller -- I have a real love for his prime period as a writer for other artists: Daredevil: Born Again, Hard Boiled, Elektra: Assassin -- but it is a truly masterful piece of comics. The Dark Knight Returns represents Frank Miller at the peak of his powers, transitioning from an experimental period to a stronger narrative one that's been described as cinematic, but that remains indelibly a master work of sequential art.

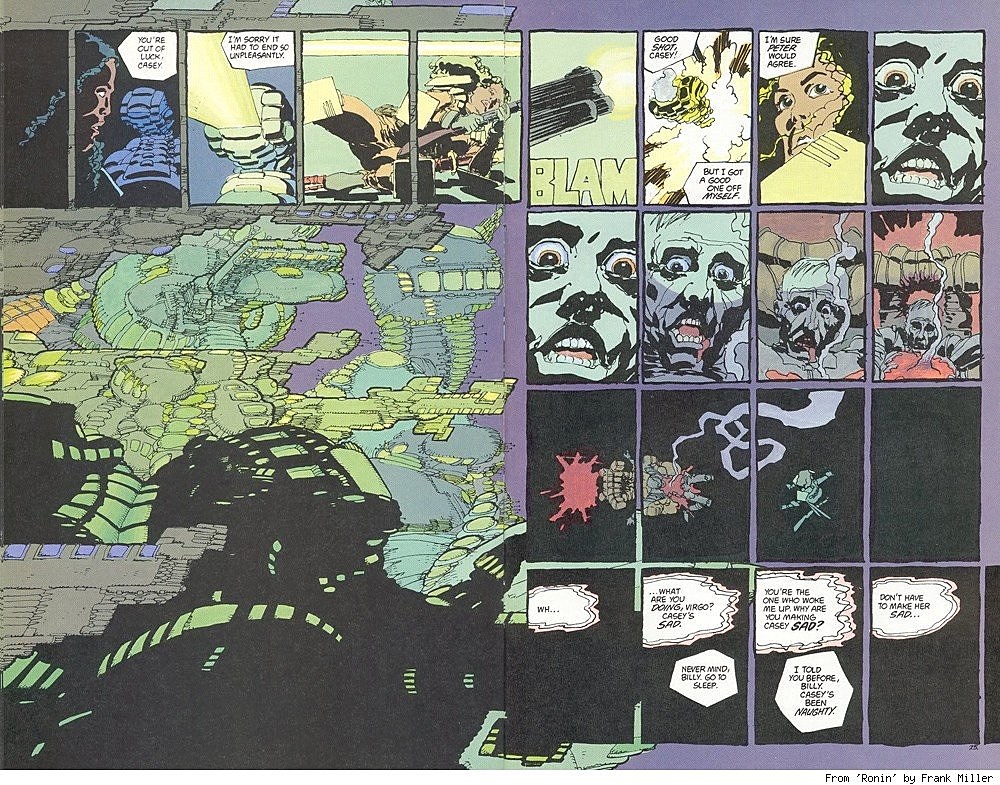

Before beginning The Dark Knight Returns, Miller had devised his own original miniseries, Ronin. Now collected in a single volume, that book was Miller pushing his own boundaries as a storyteller, artist and writer, experimenting with style and technique as much as he was capable of at the time. The transition from Ronin to Dark Knight Returns is one of the most compelling periods to study Miller's output. In Ronin, you are looking at a young artist with relatively unchecked freedom trying everything he can while the powers that be still allow him the chance. Miller's experimentation with layout -- including the 16-panel, four-tier grid that defines The Dark Knight Returns -- makes its first appearance in Ronin. But it is only one of many approaches to the page Miller toys with. The layout shares space with five-tier and three-tier grids, drifting cascades and micro-fragmentary panels carried over from his 1979-83 run on Daredevil.

There is a danger in over-emphasis on "the grid" in analyzing comics storytelling, as a grid is often just the clearest way to convey a story. Jack Kirby's four and six-panel pages are often laid out just to relate a narrative in the easiest manner possible. But with Miller, especially in this period, he uses the grid as a way to control pacing and shot sequencing. Filmic techniques like editing and montage are being used in a very comics-specific manner. In Ronin, the most compelling juxtaposition of shots is always in the action sequences or the conversations. Those scenes are done with an eye towards clarity and emphasis on the moment. The sex scene in chapter four is Miller finding the technique he would use as the template for DKR, the 16-panel grid which dices up small gestures of the characters, emphasizing minor details and slowing down simple actions to a deliberate pace. This abstracts moments by fragmenting them.

The big difference between how Miller uses this technique in Ronin and DKR is that in the former he is processing mostly single scenes. Sometimes Ronin cuts back between two or three scenes, but there remains a page-as-a-whole-unit sensibility to the Ronin page. Which is indeed the prevailing approach in comics to convey setting, geography or tone, or in order to not confuse the reader. But in DKR, Miller starts cutting scene to scene on a single page in very interesting ways.

The techniques used in Howard Chaykin's American Flagg! have a palpable bearing on DKR. Both comics are greatly influenced by television and the way it flattens transitions between moments, but Flagg's real innovations -- and it is truly innovative -- are in things like page layout, sound design through Ken Bruzenak's lettering, and delivering information so fast that the audience only has the choice to keep up or put the book down. The first year of Flagg! is the largest shared influence on both DKR and Watchmen, mostly in that quality of how information is doled out (also, Miller, Moore, and Gibbons had probably seen Taxi Driver and Dr. Strangelove, but we're talking comics here). Interestingly, American Flagg! and Miller's Ronin were also drawn in the same studio, only a few feet from each other.

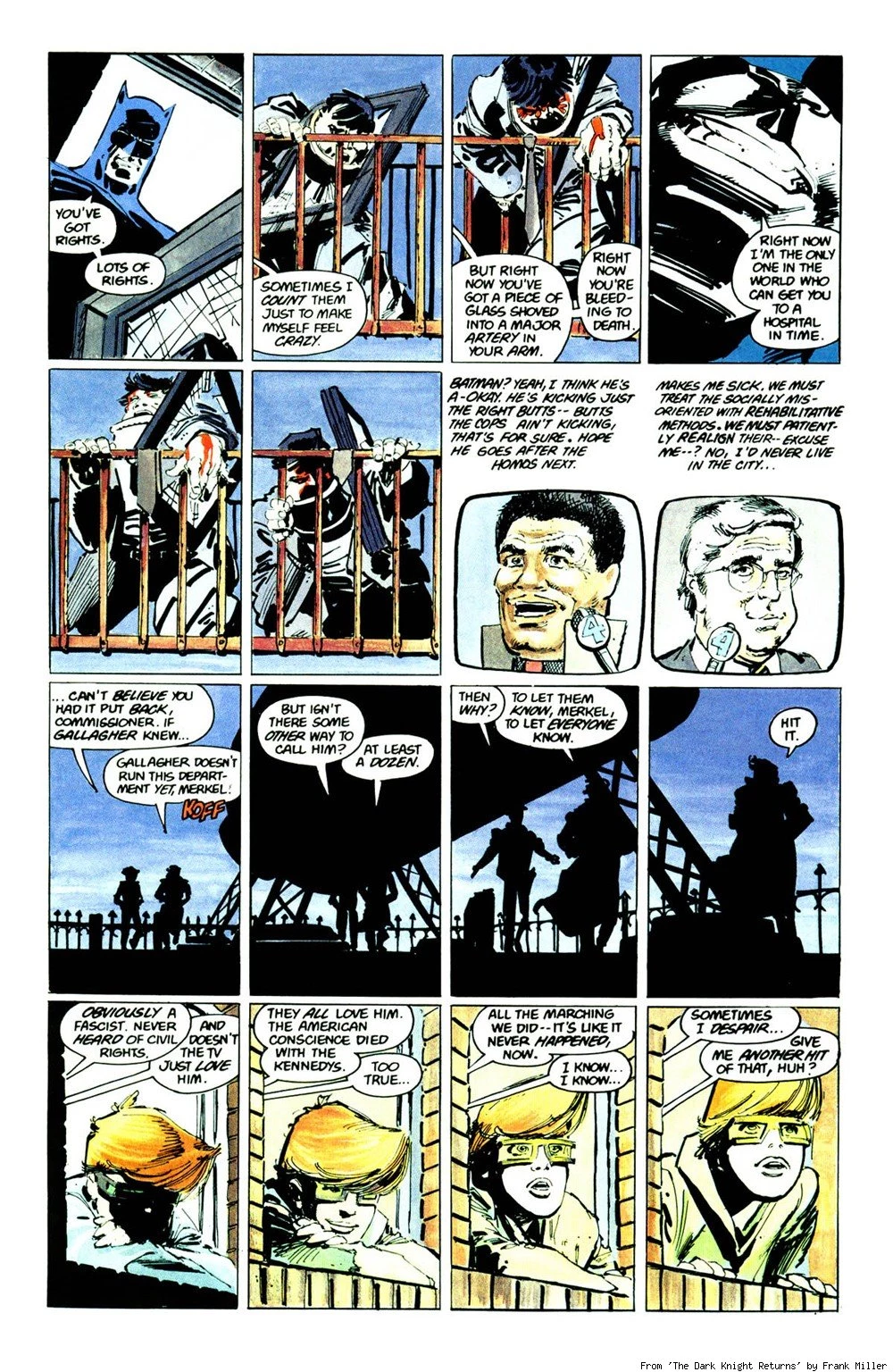

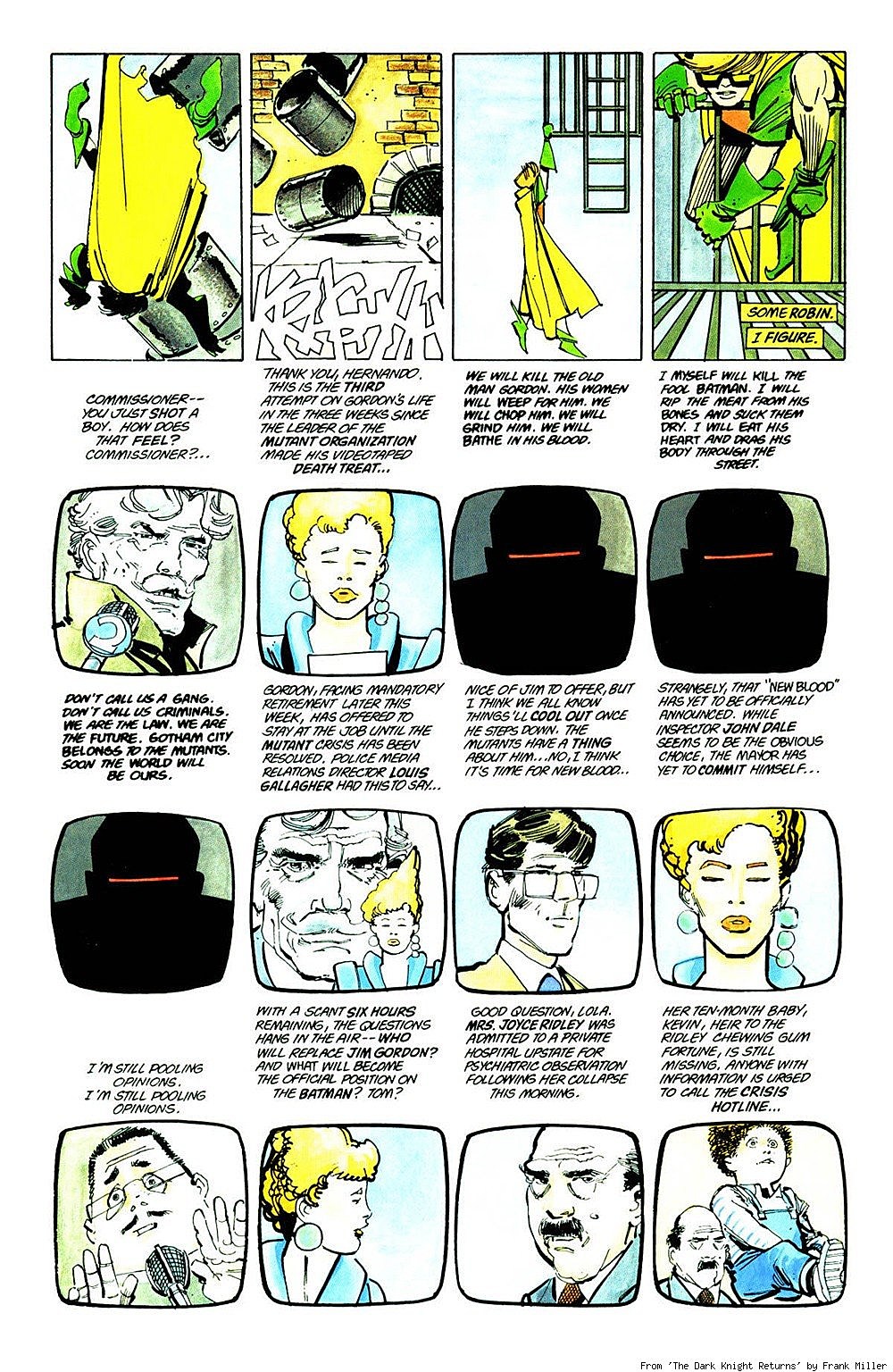

The influence of television is seen in Chaykin's pages through repetition, distortion, and scattershot information overload. For Miller, he uses the TV-shaped panels to constantly comment and complicate the "real" story panels elsewhere on the page, making television a kind of expositional/ironic/greek chorus element in the story. This approach is also a way for Miller to establish extremely quick, non-traditional transitions between narrative threads.

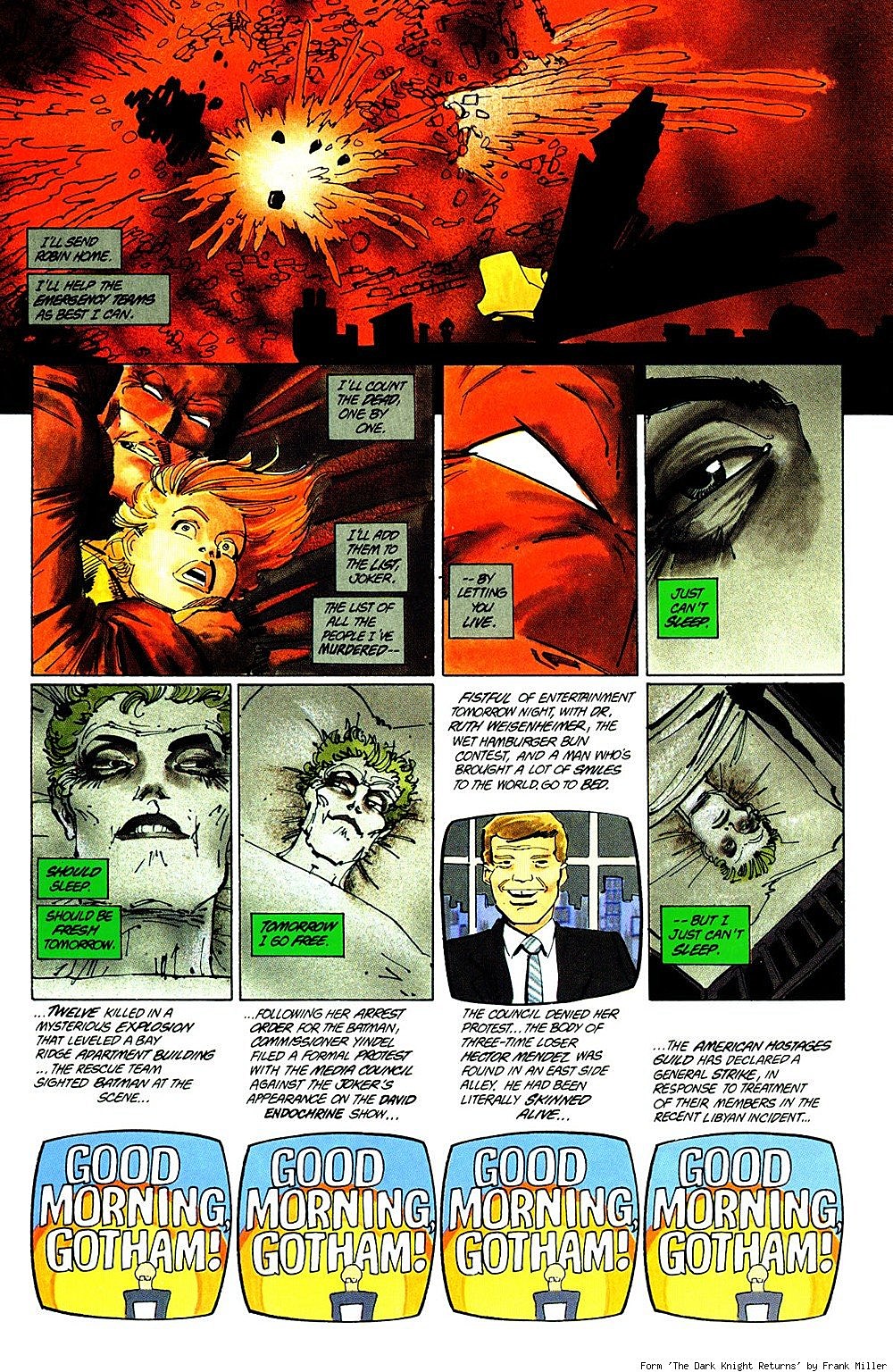

At this stage Miller's skill as a cartoonist was at a level where he could forgo traditional establishing shots and other easy storytelling tools. The sense of geography and continuity in his pages are completely unlike traditionally edited comics. While most of the television screen panels never get more complex than talking heads, the total lack of familiar transitions between them dictates the pace with which the reader is expected to keep up for the rest of The Dark Knight Returns. This combined with the fragmentation and abstraction of Miller's use of the 16-panel grid results in a fearlessness in how he edits his scene-to-scene and moment-to-moment juxtapositions. Sometimes there are pages containing five or six scenes, or characters established for a single panel without explanation, or simple gestures given great weight. Image become motifs in the narrative, a flashback expands brief seconds of childhood trauma into endless slow motion, a cut to a single panel gives a visceral sense of an internal, split-second flash of image as memory.

It must be emphasized that these DKR pages are also incredibly clear and easy to understand. The clarity owes a lot to the percussive quality of the consistent grid approach. The 16 panels and four tiers are used for rhythm as much as they are for structure. If we're describing the panels as beats, those that break into two slots on the grid are cymbal splashes, while full page splashes are gongs. Visually, the base unit of storytelling in the book is established so consistently that panels which the reader might be tempted to disregard in another book have more narrative and aesthetic weight. Larger vertical panels create scale and tension, while expanding horizontally creates scope and depth. This decision calls on Miller to be as simple and direct with panel composition as he can. While there is an expressiveness in the way Miller abstracts details, he never tries to obscure. DKR is full of faces, closeups, and gestures. All are clear, all emphatic. An explosion is an explosion. There are no real establishing shots unless used to convey mood. While it is a film term, this isn't a comic that has "coverage." Every panel, every page, is designed to communicate and forward the narrative, either through direct "here's what happens next" delivery or for nuance. Miller's panels are meant to communicate quickly and clearly, but with flourish. It's an impulse that would eventually lead to the Sam Fuller and Jose Muñoz tabloid approach Miller pursues in the early Sin City stories.

While Alan Moore has spoken of the nine-panel grid used in Watchmen as "cinematic," the montage-heavy approach Miller uses in DKR is a way to tell its story in an even more cinematic manner -- while staying firmly entrenched as a work of comics. The dissection and juxtaposition of moments for emotional reaction is what can be called the most "cinematic" aspect of DKR, whereas using the term to describe Watchmen would mean the slow, nearly austere approach to transitions and zooms into details of the scene at hand. Watchmen is legitimately novelistic in approach. It is an internal story. Miller's cinematic approach is much more visceral, yet also something that revels more in being a comic and using the language of comics to tell the story.

(Incidentally, Paul Verhoeven's RoboCop receives quite a lot from The Dark Knight Returns, specifically Miller's approach to editing, characterization, satire, and media. The way in which expository and non-expository television broadcasts are intercut into the narrative of both works, point-of-view being dissected by bursts of sharply graphic flashback, how closeups are used in fragments to abstract... all of it's there. Strangely enough, Miller's time working as a screenwriter on the RoboCop sequels -- with directors Irvin Kirshner and to a lesser extent Fred Dekker -- seems to recall his own sense of scale and tone, but the films themselves ignore the visual grammar that defined DKR).

The choices made in telling the story in The Dark Knight Returns are as much a part of it as its incidents of plot. The satirical approach to media in DKR is only effective when the constant chatter and flicker of television news is present in the actual telling of the story. The repetition and recursion to moments of the Waynes' murder -- the pearls, the gun, the hand grabbing at the young boy's shirt -- are what create the emotional basis of Batman's character as much as how Miller simply shows the dark figure moving across the page. There is no way to divorce how Miller creates resonance with character from how resonant the character is. This is a story which could only be told this way, and any variation would have changed it completely. Which is what makes The Dark Knight Returns worthwhile -- not for telling the "best" Batman story, not for how it's drawn or how it's written, not for its politics or its place in the canon. Above all else, it is a masterful use of the comic medium to tell a story. Miller tells the story simply and directly, using the most difficult -- and rewarding -- of methods.

More From ComicsAlliance