Talking With Adam Hines, Creator of ‘Duncan the Wonder Dog’ (and a 33-Page Preview!)

We finished our roundup of the year's 10 best comics and graphic novels yesterday with our #1 entry, Duncan the Wonder Dog by Adam Hines. Since we loved the book enough to give it top honors, we decided to dig a little deeper into the 400-page tour de force and talk with Hines about his opinions on animal rights, how he taught himself the art of comics, and his plans for the future. The book is sold out until a reprint coming from Adhouse in March, but we've also got a 33-page preview of Duncan the Wonder Dog after the interview to give you a taste of the book now. Enjoy!

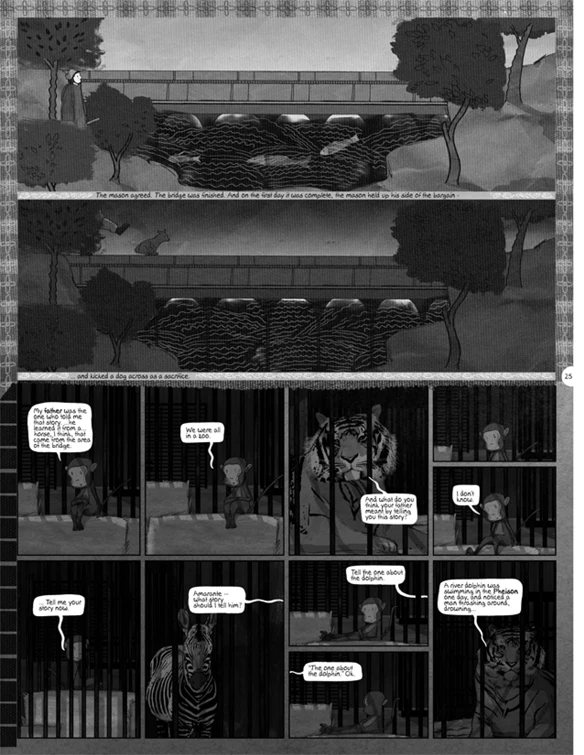

ComicsAlliance: The book begins with two stories unfold simultaneously: a boxing match (between two humans) and a parable told from a tiger to a monkey about a man sacrificing an animal. Was there a connection there?

Adam Hines: Well first, the main reason I had the particular story about the sacrificed dog being punted over a bridge for the benefit of humanity was to connect that to the scene immediately after, where Laika is launched into space and the last panel shows her shuttle crossing a bridge, as another sacrifice. The boxing match was to elude to the coming confrontations, and the obsession humans can have with the superficial brutality of it when surrounded by very real brutality. But a lot of the intellectual reasons are dwarfed for me by if something just "feels right," and it felt right to parallel those two scenes.

CA: There's a mathematical theme that runs through a lot of the book beginning with the references to Pythagoras in the beginning, and the philosophy that the mathematical is not separate from the physical or the spiritual. It was an interesting undertone to a book that was -- for lack of a better word -- extremely humanistic at its core.

AH: Yes, it will continue to play a role in the coming books, and it was important to me to open with that in particular because its going to be a huge running theme for the entire series, about how we see math and what it actually "is."

me: well, the Pythagorean idea is that it is a quality that infuses everything

CA: And I was trying to figure out if the mathematical philosophy was significant in its own right, or because it was emblematic of, I don't know, a general holistic sense of existence.

AH: Yes, and I like that you can think of that almost as the concept of the Universal God, the creator who is found within everything instead of an outside figure. It's meant to kind of shed light on the qualities in animals, and other qualities that we don't necessarily pay attention to or even understand.

CA: Pantheism, sort of?

AH: Yes, exactly.

CA: But the primary theme has to do with the relationship between humans and animals, or the relationship between the world of humans and the world of animals. It was interesting to see the way you reimagined animals as speaking beings.

CA: But the primary theme has to do with the relationship between humans and animals, or the relationship between the world of humans and the world of animals. It was interesting to see the way you reimagined animals as speaking beings.

AH: Yes, it was (obviously) a hard thing to try and depict the subjective world of wild animals and make it feel honest. I pulled back a few times just for the sake of clarity, but I tried to make it seem like some sort of compromise would be almost impossible because they're so distinct.

CA: The idea of anthropomorphism was really interesting to me in the book, because it obviously conjures these really intricate and sympathetic portraits of these animals and their worlds, and brings them to life. And it does it, to a certain extent, by making them more human. Which is why it's effective.

AH: Yeah it was a tightrope act, and one that I don't think I accomplished as well as I could have all the way through. I wanted the animals to be very clearly alien to us, with very little avenues of comparison, but the fact is we do all have the same basic needs, and even beyond that animals play and relax and get angry and yadda yadda. So I'm glad it worked for you. I mean, just making them talk is going to cut out half of their real world "otherness."

CA: What's the difference between the animals in this world and ours?

AH: Animals's train of thoughts are completely unknowable, and just that I made them knowable and relatable I think does the reality a disservice. But in trying to show how "we're all in this together." I hope it justifies the cheat.

CA: I mean, they've varied, also. Or they seemed that way. Like, Voltaire doesn't act the same way that monkeys do. And neither of them act like the birds.

AH: Yeah, in later volumes I'm going to try and expand on the fact that its not really HUMANS and ANIMALS, its every single animal species and their own very unique patterns of life. I think its one way humans in the real world assert our unconscious dominance, is by placing every other species in one canister and calling it a day.

CA: Why are all the animals named after philosophers and mathematicians? Just creating a greater sense of otherness, or something more than that?

AH: All of them Greek/Roman names for reasons that will be expounded on later, but my "gut" reason was that I liked how they sounded: They're recognizably names, but not anything you hear every day. And I wrestled with giving them names at all.

CA: WIthout names, it would have been easier for them to seem indistinct or quickly dismissed, especially since names are a lot of how we see the self. And you have the whole idea that naming a thing gives you power over them, and that it reinforces the power structure we see throughout the book.

AH: It's so important, it really is. Eventually having to give them names is why I had Pompeii give that speech to John in his house about why animals have names and why humans have names. I wanted to give the sense that they are almost assigned names like a natural process of learning how to walk, while for people its a more conscious decision.

CA: I can see the book making a lot of people think a lot more deeply about animals and consciousness and where rights begin and end.

AH: I try to avoid framing the issue as an issue of "rights" since its a concept that humans invented, and so can give it or take it from who we see fit. I always try to look at it as "welfare," since that is outside of us and objective. Are we denying or providing welfare, that sort of thing, instead of what "rights" a horse has, you know?

CA: Yeah, once you create a system of rights that asserts itself as authoritative, your welfare depends to a large degree on how you are framed or categorized by that system.

AH: Yeah, exactly. I don't trust other people's definition of what rights are and how that frames animals in the conversation.

CA: When we met at SPX, I remember you telling me you had no formal art training, which is pretty astonishing. What did you do to teach yourself?

AH: Well, just everything really. I'm not a "sketchbook" guy who always loves to be drawing and is just thrilled to be putting marks down on paper. I have to have a goal in mind, or I just won't do it. So wanting to make the book forced me to learn things as they came up. I knew very little of Photoshop's tools when I started, but now I can pretty much teach a class on it. It's just better for me to make mistakes and learn from them than have any sort of instructor try and hold my hand... Most of the comic artists that I admire have really striking originals, where everything is pretty much plotted out, drawn and inked all on one large piece of bristol, but I just can't work that way. I found very quickly that I liked best to work in pieces, scan everything in and put the different elements together in the computer. I think Spiegleman working like that around The Shadow of No Towers, but he's the only cartoonist who I really respect who works that way, I think.

CA: There's a very multimedia approach to what you do -- including all kinds of textures, covers, library cards, newspaper clippings as sort of interstitial flourishes.

AH: Yeah, that came about from wanting to take advantage of the "openness" of comics. Comics for me is really the ability to do anything you want on any page in a book, and to only draw characters and stories in in a very representational manner seems not to be utilizing it to its full potential.

CA: The story in Duncan is more than just a linear narrative, moving around to a lot of different perspectives and interludes like the nature sequences, and particularly the diary pages which could have even been a whole book onto themselves. What was the intent?

AH: I wanted to always have in the periphery around the main story and these little vignettes to kind of pay "respect" as it were to the "stories" that the book wasn't focusing on. And I like that way of storytelling that's very tangential, where you follow other incidents that may be thematically important but otherwise are completely their own thing.

CA: You worked on the book for seven years; how much of the story did you have in mind from the outset and how much evolved? Were the standalone vignettes something that accumulated around the main story over time or something that unfolded in a more linear way?

AH: I charted the entire series first, deciding what would be contained in each book. Then when I had that pretty much set I wrote the script of the first. The big strokes were always plotted out from the outset. "Here's a scene with Voltaire, and then after I'll have a scene with Jack..." and probably about half of the vignettes. It was only when I was knee deep in it that I decided I wanted even more interludes and tangents, either to give the reader a break or the story a breather.

CA: And they all obviously seem to orbit the same ideas or themes.

AH: I'm clearly a one track mind. I tried to make it seem cohesive, yes... Now that the book is out it's been interesting to hear people's responses. I've heard more than a few, "I had no idea what was going on in the first 150 pages, but then it really picked up!" The tangents for me are the best part of the book! But some people get frustrated and I can completely understand that. I hope for you its more a gentle rubbing than an annoying puzzle. My hope is that people just take it one page at a time... Its very hard for me to see it objectively, since I know exactly why I put everything in there, you know?

CA: What's your perspective on the welfare of animals? Judging from the primary theme of a book series that you're probably going to put decades of your life into, it seems like it's something that's probably important to you.

AH: I would hope so! Yeah, its very important to me, probably the most important thing in my life honestly. I think its such a huge, all encompassing issue that effects almost every decision you make from the moment you wake up.

CA: Has it always been that way? And how does that affect and inform the decisions you make?

AH: Pretty much. Not of course since I was an infant or anything, but I think once I started learning about what the food was and where the clothes came from and what extinction was and on and on it just overran me. As for the decisions: I avoid eating animal products and live a basically vegan lifestyle, but vegan can mean many things, and at some point to simply live in modern society you have take advantage of and use products and services that are around because hordes of animals died. But that line of thinking can lead you to also say that you can't live in a country that was taken over by force, and then poof you have to live on the moon, so its a balancing act between what I can do and what I reasonably can't.

CA: Right. You still have to live in the world. Especially if you want to have any influence on the world.

AH: Yeah, I mean, if I'm being completely honest, could I live in a log cabin by myself and really cut down my negative impact and abuse of ill gotten services? Yes, of course, but then what would that help exactly? A little bit of hypocrisy is justified for me if you can "outweigh" it with change.

CA: This also jumped out at me:"A smart opponent of any system of beliefs will try show, will seek to exhibit that the system in question tolerates moral absurdities."

AH: Yeah, that idea came from an essay I think William Gass wrote. The system of beliefs in this instance is the system will all pretty much subside in, and the moral absurdity of killing so many millions of animals.

CA: You know, my first thought when I walked away from the book, afterwards, was, "Man, wouldn't it be totally messed up if things were really like this?" And then a couple seconds later, "Oh wait, they kind of are."

AH: Haha, yeah. Nothing is really different except they can talk.

CA: Well, you've got... eight more books planned in the series? Do you expect them to be equivalent length and take you the same amount of time per book?

AH: Book One, Five, and Nine are 400, Two and Six are 300. And Three/Four and Seven/Eight will be a combined 300/350, but split between the two slimmer volumes that will come out in relatively quick succession. So it won't take quite as long as some people have been guesstimating. I hope to be done in about 25 years. This one took seven years because it was a lot of planning for the whole series, too. I think I can finish a similar sized installment now in about four years.

CA: Yeah, that's a lot of long view. Do you think you'll do any other comics in between, or just focus on this?

AH: Yeah, I have a few other ideas that would take like a year each? Hopefully? And I'm taking breaks in-between to do other projects.

CA: Did you think the relationship between Voltaire and a human woman might be controversial?

AH: I honestly don't know. It will never get more explicit than it is in this volume. I don't know if comics even have the breadth of attention to get the type of people who would actually be "offended" by it. I think comics readers are pretty jaded and expecting to see weirdness.

CA: There was also definitely a thread of optimism throughout all of it, the idea that "everything seems to aim at some good" or refuting the idea "that nothing can matter if everything ends." That sort of cosmic scope it pulls out to at the end, and then zooms back in to the mayflies, the most ephemeral of all possible lives. The emphasis on the value inherent in life, or wanting to live.

AH: I'm glad you saw that in it. I was worried that it would be looked upon as a bit of a downer, but such a big part of it for me was the notion that, hey, if you're alive, and we're alive, right now, than there's still possibility and there's still hope and there's an inherent good just in that.

33-Page Preview of Duncan the Wonder Dog:

More From ComicsAlliance

![Colinet And Charretier Announce ‘The Infinite Loop Volume 2: Nothing But The Truth’ [Exclusive Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Loop01.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Five Stars: Starting At The End With Jeff Smith [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/FiveStars-Smith.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Take Me to Your Teacher: Trevor Mueller and Gabo Discuss ‘Albert the Alien’ [Webcomic Q&A]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/0ALBERTVOL3_COVER_notitle-copy.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![‘Runaways’ Meets ‘Coraline’ in Cait May and Trevor Bream’s ‘Irregular’ [Webcomic Q&A]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Irregular_Banner.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Nun Greater: Yamino and Ash Share ‘Sister Claire’ [Webcomic Q&A]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/11/unnamed-3.png?w=980&q=75)

![When Everything Is Pink, Nothing Is Pink: Sarah Stern On Color And Creativity [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Cindersong-feat.jpg?w=980&q=75)