‘Ender’s Game’ Meets ‘Hunger Games’ in Douglas Rushkoff’s ‘A.D.D.: Adolescent Demo Division’

In Douglas Rushkoff's new graphic novel A.D.D.: Adolescent Demo Division, published by Vertigo Comics with art by Goran Sudzuka and José Marzán Jr., the kids of the Adolescent Demo Division are living the teen gamer's dream. They're the world's top competitive videogamers; they star in their own reality television show, and they have round-the-clock access to all the media they could ever want. They're told that, once they hone their skills, they'll "Level Up" to the next stage of their incredible lives. It's true, in a way. As they train, the A.D.D. squad discovers abilities far beyond those of normal videogamers -- and that their corporate sponsor has roped them into something far more deadly and real.The comic certainly wears its Orson Scott Card influences on its sleeve. Much like the children of Ender's Game, Team A.D.D. is a group of kids living inside a media lab. They've never known their parents, and the only adults they have contact with are the teachers, doctors and administrators of their school, which is owned by the company NextGen. It's a corporate-run version of Card's militaristic Battle School where the students spend their days training to be the best gamers in the world. It also has Battle School's gender ratio, with just one female gamer amidst all that adolescent testosterone.

The first thing we learn about the A.D.D.ers is that they're also famous. They star in their own reality TV show, and kids line up at the mall to get their autographs. But the gamers, known as Betas, are also too warped and damaged to interact normally with the real world. Lionel, our point-of-view character, is so distracted by the subliminal messages he sees in games that he can't impress upon anyone just why they're so disturbing. His teammate Takai is autistic, capable of communicating only through a wristband voice synthesizer. The same abilities that let Kasinda, the team's sole female member, dodge virtual projectiles also drive her to avoid all physical contact.

Plus, all of the students are hypercompetitive, each hoping to become the school's top gamer so they can eventually "Level Up." None of the Betas know what Leveling Up entails, but in true teenage fashion, they devise plenty of comforting rumors. Once you've Leveled Up, you're reunited with your parents and you get to join the real world, or so the story goes. The facility's adults refuse to confirm or deny the boys' fairytales. They know it's easier to keep the kids calm and contained when they think they're just playing a larger game.

Rushkoff is a media theorist who has focused much of his attention on the role of technology in society, and the concepts hhe introduces are as intriguing as you'd expect are some. Lionel monologues about the way the placement of a logo on an avatar lets a company "brand" kids while they play. He picks apart the way advertisements and other media prime kids for sex, violence and consumerism. The simultaneous homophobia and misogyny that you hear spewed across XBox Live is institutionalized among the Betas, who have little interest in one flesh and blood girl who walks among them. (That, too, reminds me of some of the less comfortable aspects of Ender's Game.)

The comic also deals to some degree with spectrum disorders like autism and yes, Attention Deficit Disorder. As Rushkoff told Wired, the increasing prevalence of those disorders "often gets blamed on videogames and computer use, but I've been wondering since the mid-'90s if it's less a bug than a feature when you're living in a world that wants to program you everywhere you look."

There's also the suggestion that kids raised on media can't recognize real violence when they see it -- and that leaves them vulnerable to manipulation. It reminds me, in the best way, of some of the more cynical corners of the Internet, where people believe that every image is Photoshopped and every slice of life news story is a viral marketing ploy.

But despite all Rushkoff's beautiful ideas about youth culture, Internet culture and media bouncing around the comic, A.D.D. never quite pushes its critique of media and consumer culture far enough. For all those ominous references to subliminal messaging, we never really see what effect these nefarious media schemes have on the normal teenage psyche. In fact, despite NextGen's media-programming capabilities, the outside world seems no more dystopian than our own. Perhaps that's Rushkoff's point, but he doesn't hit it clearly enough.

But despite all Rushkoff's beautiful ideas about youth culture, Internet culture and media bouncing around the comic, A.D.D. never quite pushes its critique of media and consumer culture far enough. For all those ominous references to subliminal messaging, we never really see what effect these nefarious media schemes have on the normal teenage psyche. In fact, despite NextGen's media-programming capabilities, the outside world seems no more dystopian than our own. Perhaps that's Rushkoff's point, but he doesn't hit it clearly enough.

It also fails to make good on its early promises. The reality TV show business is dropped after the first few pages, which is a shame. If we could have seen the reality of life inside NextGen juxtaposed with the way the kids are packaged to the masses, that would have been a nice companion to Rushkoff's other media critiques. Plus, it might have given me some of the Hunger Games-style violence voyeurism I was craving at that point.

A.D.D. might want to compare itself to Ender's Game and The Hunger Games, but the plot more closely reminds me of that other evil boarding school comic, Image's Morning Glories, with its children are born under mysterious circumstances and touch of mayhem and murder. As Lionel and his friends come into their superpowers and begin to understand that their home isn't quite the happy haven of videogamers, A.D.D. becomes a fairly straightforward quest for answers. Certainly there's nothing wrong with a classic escape scene or adults double-crossing one another, but these are tropes I've seen too recently and with a good deal more punch.

I suspect A.D.D. is one of those comics that would have worked better as a continuing series, where mysteries had more time to linger in the background and Rushkoff's ideas had more room to develop and explore their paranoid possibilities. I'd happily read an ongoing comic about these subliminal messaging testers framed around a reality show, topical concerns that could have been explored with more depth than 152 pages could allow.

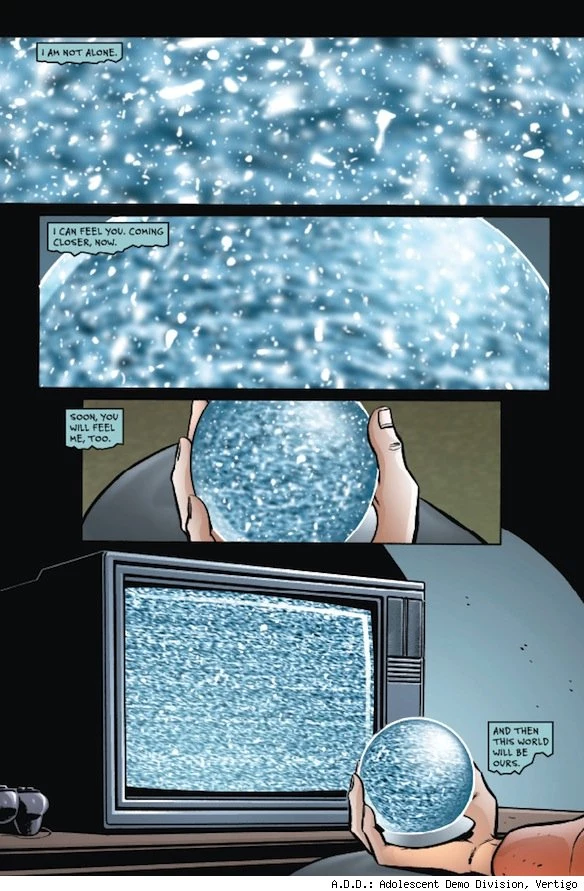

Below are the opening pages of A.D.D., featuring a mysterious character who knows far more about the Betas than they know about themselves.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Vertigo Goes Same-Day Digital, Announces Paul Cornell’s ‘Saucer Country’ [NYCC 2011]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2011/10/vertigonycc2011.jpg?w=980&q=75)