Ask Chris #63: Superboy and Lex Luthor: BFF?

Here at ComicsAlliance, we value our readership and are always open to what the masses of Internet readers have to say. That's every week, Senior Writer Chris Sims puts his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

Q: For good reason, you're not wild about Smallville. But what do you think about the Silver Age Superboy-Lex Luthor friendship? -- @NathanBethell

A: Even if you completely separate it from Tom Welling and Michael Rosenbaum, something that I hope I'll be able to do after years of therapy and a written apology from David Uzumeri, I'm not a big fan of the idea that Clark Kent and Lex Luthor knew each other when they were kids. I think there's a lot of appeal to it, in that it ties in to ideas of destiny and a fall that everyone but the characters themselves can see coming a mile away that lends a compelling note of tragedy to the story, but I just don't think it works for those two characters in the way that they need to work.

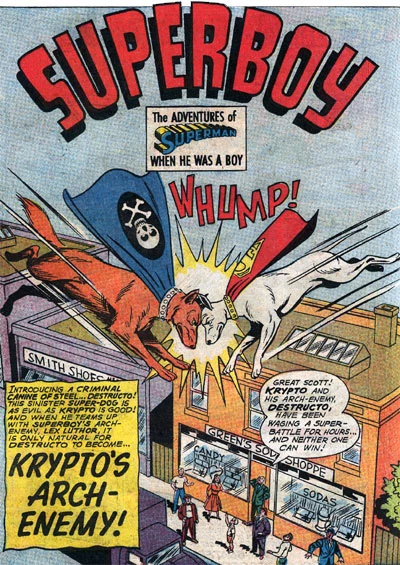

And what's more, I think it points to a larger problem with the entire concept of Superboy.Don't get me wrong: There are plenty of Superboy stories that I like a whole lot that involve Lex Luthor. There's one from 1961 one where you find out that Young Lex Luthor also had a super-powered dog named Destructo that wore an awesome Jolly Roger cape that's a pure Silver Age masterpiece:

But at the same time, I think Superboy as a concept is intrinsically flawed, with Luthor being the perfect example of why. The idea behind it, the desire to see what Superman was like when he was a kid, makes perfect sense, especially when you consider that when Superman's younger self made his first appearance in 1945, Superman comics were being outsold by Captain Marvel Adventures. It wasn't just that the stories were good, either -- although they were -- but that there was an aspect of Captain Marvel that Superman just didn't have: He was a kid who turned into a super-hero.

As much as kids like to pretend to be adults, Billy Batson took that to another level by being a kid who could turn himself into the biggest, strongest, smartest adult ever with a magic word, solving all of his problems. Superman, however, was strictly grown-up, to the point where he had an actual job that required a suit and tie and coworkers. In that respect, it's easy to see why they'd go with the simple route of not only competing with Captain Marvel on his own terms, but doing so in a way that would make Superman more relatable to kids by satisfying the natural curiosity of showing what he was like when he was younger.

The problem was that the answer to "Superman, what were you like when you were a boy?" was "pretty much exactly like I am now, only shorter."

The problem was that the answer to "Superman, what were you like when you were a boy?" was "pretty much exactly like I am now, only shorter."

Aside from the location of the stories, there's just not a lot of difference between Superman and Superboy, and for good reason. Even before the heights of his Silver Age glory, Superman had already been established as a being of Ultimate Good, because really, that's the only way that an indestructible being of phenomenal power isn't also absolutely terrifying. We like Superman because we can like Superman; we trust him because we have no reason not to trust him.

That's a great part of his character, the idea that, as Grant Morrison said, "we made up the story of a man who will never let us down," but it doesn't leave a lot of wiggle room. After all, the last thing you want to do is have a story showing how your all-powerful hero used to be a real jerk, because then you've got a reason not to trust him.

The only thing setting Superboy apart from his grown-up counterpart were the details. He lived in Smallville rather than Metropolis and had a nosy girlfriend named Lang instead of Lane, but other than that, the stories were more or less interchangeable. A big exception came with the advent of the Legion of Super-Heroes, a plot device that allowed for a section of the DC Universe that was almost completely isolated from everything else, where Superboy was on equal terms with a larger ensemble cast. But even then, I tend to prefer the Post-Zero Hour idea of the Legion, where they were inspired to do good in the Universe by the ideals of Superman rather than the guy himself.

My opinion of Smallville -- the town, not the show, although brother, do I have opinions on that -- is very similar to my opinion of Jor-El. As I've said before, once Jor-El puts the baby into the rocketship, we never need to see him again. His part in the story is over. Along the same lines, once Superman goes to Metropolis, we don't really ever need to see Smallvile again, although I do like Superman having a place where he can go to talk to his parents.

That's not to say that Clark Kent's life on Smallville is not an extremely important aspect of his character, because it is. But it's also so perfectly, poetically simple that it doesn't really need a whole lot of explanation. Even the idea that Clark Kent is from a family of farmers plays beautifully into the larger mythology, because what do Farmers do? They grow food. They turn the light of the sun into something people need to live.

It's beautiful because it's simple, but at the same time, you can't really do a Superman story there, because that's not where Superman lives. It's just as important to Superman's character that he lives in a bustling, active city, full of dangers both obvious and hidden, and crowded with people who all need his help. Smallville is a refuge, a place where things are grown, but Metropolis is where things go to work. Smallville's the place where Superman used to live, and a Superman story should never be about what Superman used to do.

But that all points to a bigger flaw: You know how Superboy's story ends. He flies off to Metropolis and becomes Superman, something that was a foregone conclusion seven years before Superboy was created. The goal, then, is to make his early days as interesting as they could be, and much like the Smallville show, one of the ways creators attempted to do that was by bringing in other aspects of Superman's adult life. My favorite example of this is the story where Superboy looks into the future to see his pals in the Justice League like Green Arrow, and sure enough, Oliver Queen moves to town the next day.

Superboy then spends the next 11 pages trying to trick Ollie into using a bow and arrow and then making him dress up as Robin Hood for a school parade, even though Ollie actually wanted to be Wyatt Earp.

There's also an issue where he meets up with a young Bruce Wayne, and another with Aqualad (they're all collected in the Superboy's Greatest Team-Ups paperback from last year, which is well worth reading), and they all stem from the same desire to see what these heroes were like in they were kids. And they also all create a gigantic problem.

Namely, hey Superboy! If you have a Time Viewer, and you also have the ability to travel through time under your own power, and you can also see Batman in the future, maybe you should stop the Waynes from being murdered. But obviously Superboy can't do that, because it's just as set in stone that young Bruce Wayne's parents get killed and becomes Batman as it is that Superboy becomes Superman. They all have a "destiny" that they have to reach because those stories have already been (and continue to be) written.

Now, all that said, I don't think that stories of younger versions of characters like Superman or Spider-Man or Robin Hood, or even flashback stories to their past, are intrinsically bad or without merit. But I do think that if you're setting it in the same timeline that's already established, without a plan for showing a new angle on things, you're not really adding anything. And because Superboy lives in a shared universe where it's not just his stories that have already been established, the more you pull in, the more ultimately pointless those stories are revealed to be.

Which brings us, at long last, back to Lex Luthor. The fact that he's even in the stories is just a testament to how little the Superboy and Superman stories differed from each other -- Superman fights brilliant criminal scientist Lex Luthor, so Superboy fights brilliant juvenile delinquent scientist Young Lex Luthor -- but the twist that they were originally friends adds a whole new layer to both of the stoires. It's the sort of revelation that actually adds to the mythology in a way that doesn't invalidate -- and isn't invalidated by -- the stories it's trying to mesh with.

Which brings us, at long last, back to Lex Luthor. The fact that he's even in the stories is just a testament to how little the Superboy and Superman stories differed from each other -- Superman fights brilliant criminal scientist Lex Luthor, so Superboy fights brilliant juvenile delinquent scientist Young Lex Luthor -- but the twist that they were originally friends adds a whole new layer to both of the stoires. It's the sort of revelation that actually adds to the mythology in a way that doesn't invalidate -- and isn't invalidated by -- the stories it's trying to mesh with.

Namedrop Alert: I was discussing the question with Chris Roberson, the current writer of Superman, and unlike me, he's all for the Superboy/Lex friendship, for the reason that it sets their relationship up in a way that no other interaction can. As he said, you never hate anyone as much as someone you used to like. It makes Luthor's actions more personally directed at Superman; every single criminal act he commits becomes one done from spite, an explicit reminder that Luthor hates his former friend and everything he stands for on a personal level.

It also has the added benefit of making Luthor's redemption a goal that the adult Superman has for more reasons than just "he's a smart guy who could probably help people." Through no fault of his own, Superman failed at turning someone away from a life of crime, and that failure continues to haunt him through his adulthood. It humanizes him, and gives him a goal. In a world where Superman and Luthor were friends, Luthor's redemption becomes Superman's ultimate triumph.

I definitely see the appeal there. I think that's why so many people are attracted to the "Lex Luthor is Leo Quintum" theory of All-Star Superman, because it makes Superman's final act the uplifting of a man so completely devoted to evil that he proudly idolizes Adolf Hitler, turning him good just by virtue of his presence.

But at the same time, while it's an interesting idea and one that could certainly work in the context of All Star Superman as an isolated story, but in the larger context of Superman as a going concern, I think it's a disservice to both characters. Their enmity doesn't need a failure on Superboy's part, and Lex Luthor doesn't need any more reason to hate Superman than just the fact that he's Superman.

Luthor and Superman should be opposites, but more than that, they should be equal opposites. When they meet, it shouldn't be while they're still growing; they should have been honed into the men they are and will be forever. Having them meet as kids takes that away from Lex -- especially with Superboy being the motivating factor that led him to crime -- but it takes nothing from Superboy. It puts them on unequal footing by making Superboy responsible for Luthor as his enemy. There's room for decent story hooks there about resentment and responsibility, at the end of the day it builds Superboy while undermining Luthor's character.

And as a character, Luthor defines Superman by being his opposite. Superman's the Ultimate Good, the best of humanity reflected in someone who came from somewhere else because he was embraced. Luthor, then, should be unrepentantly Evil, reflecting the worst in us by being arrogant, vindictive and petty. He hates Superman because he can't not hate him.

Superman is everything Luthor is not, right down to the fact that Superman disguises himself to live with anonymity, while Luthor -- whether the science-crook of the Silver Age, the ruthless Byrne-era businessman or the Modern Age synthesis of the two that was best done in Superman: The Animated Series -- wants everyone in the world to know who he is. And given a choice, the people choose the man who uses his powers to help them rather than the man who hoards power for himself, the man who flies up to catch them when they fall instead of lording over them from a tower.

That alone is enough to make him hate Superman, and each time Lex fails to destroy his enemy -- something that, before Superman, had never been a problem for him -- that hatred grows, because he's confronted with living, breathing flying proof of his failure. And with it, the knowledge that everything he's done, every crime, every person he's killed, every bit of power that he's clawed his way into possessing holds no value in the face of something that embodies the morality he's spent his whole life feeling superior to. He sees what he could be every day, and needs to destroy it in order to validate his own existence, because the only alternative is admitting that his entire life has been meaningless. He would have to admit he was wrong, the one thing he can never do.

That is the tragedy of Lex Luthor, and the idea that they were friends as children, before he achieved the status that would give their conflict its meaning, strikes me as completely unnecessary

That's all we have for this week, but if you've got a question you'd like to see Chris tackle in a future column, just put it on Twitter with the hashtag #AskChris, or send an email to comicsalliance@gmail.com with [Ask Chris] in the subject line!

More From ComicsAlliance