![Kieron Gillen Chooses the Nuclear Option for the ‘Uncanny X-Men’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2011/11/uncannyxmen1preview2-1320340102.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Kieron Gillen Chooses the Nuclear Option for the ‘Uncanny X-Men’ [Interview]

This week Marvel Comics' newly relaunched Uncanny X-Men hit shelves (and digital stores), with a first issue by writer Kieron Gillen and artist Carlos Pacheco introducing an "Extinction team" of mutant heavy hitters lead by Cyclops in the wake of X-Men: Schism. ComicsAlliance talked to Gillen about why this team has taken a page from Batman's book and decided to use fear as a weapon against their enemies, turning the X-Men and their incredible powers into the nuclear deterrents of a rogue mutant state.

ComicsAlliance: How did you choose your roster for the new Uncanny X-Men out of the huge cast of potential characters?

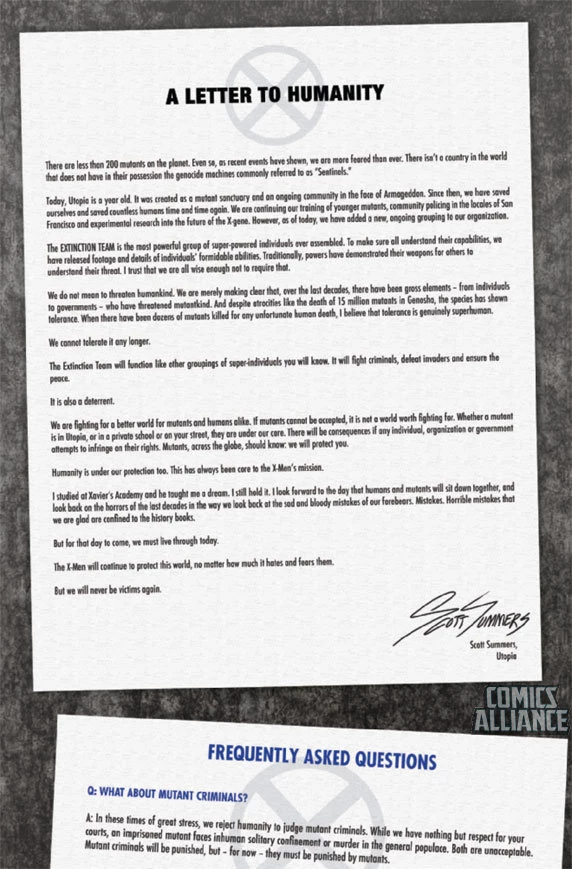

Kieron Gillen: I knew the X-Men: Schism [event] was coming, so my run up till now has actually been setting up the pieces, and the more philosophical elements. My first issue before the reboot focused on Magneto, and there's that Machiavelli meditation: "Is it better to be loved than feared?" I think if you look back whenever my [X-Men] run ends, you'll see that's my theme. I was very interested in the concept of fear. The first issue ends with a letter of Scott's -- a "Letter to Humanity" that's part of the back matter. We'll continue to protect the world that hates and fears us, but we'll never be victims again.

Kieron Gillen: I knew the X-Men: Schism [event] was coming, so my run up till now has actually been setting up the pieces, and the more philosophical elements. My first issue before the reboot focused on Magneto, and there's that Machiavelli meditation: "Is it better to be loved than feared?" I think if you look back whenever my [X-Men] run ends, you'll see that's my theme. I was very interested in the concept of fear. The first issue ends with a letter of Scott's -- a "Letter to Humanity" that's part of the back matter. We'll continue to protect the world that hates and fears us, but we'll never be victims again.

For me one of the major parts of Schism was Wolverine very much playing the idealist. Since Wolverine kind of walks out, they have to shoulder that burden to protect a world that hates and fears them. That includes [Wolverine's] school. It's actually a very paternalist attitude, "Go open your school. We'll go on protecting everyone. It's ok. Don't worry your furry little head about it." Although I kind of agree with Scotty; he sees that they haven't got time to be idealistic, because there are so few of them left.CA: Because this is war?

KG: Or, it's survival. There hasn't been a major threat to the X-Men's existence [in a while] except for the Fear Itself stuff, and it's actually been the X-Men in a position of power, which I think you only realize in retrospect. I was very interested in the idea of the X-Men actually being the government [in Utopia], and seeing how they deal with their refugee situation from Breakworld. It's a very optimistic arc, actually. The easy, cynical story to do would be turning the X-Men into everything they hated. There's so much in the book that is Sisyphean. We'll never get into a position where mutants are loved in the Marvel Universe. It's a book about societal change whose whole core concept includes an element that means we can never actually win. There's a kind of element of defeatism to that, and that's my nagging problem with writing the X-Men. But you write around that, and you can show meaningful change in some way.

CA: I like the idea of the X-Men becoming an institutional force, because it's one thing to be rebels, and a very different thing to become the government. It reminds me of the narrative arc of President Obama, where at first everyone got behind him to fight the power, and then he became the power. And once you're in charge, there are all these compromises you have to make.

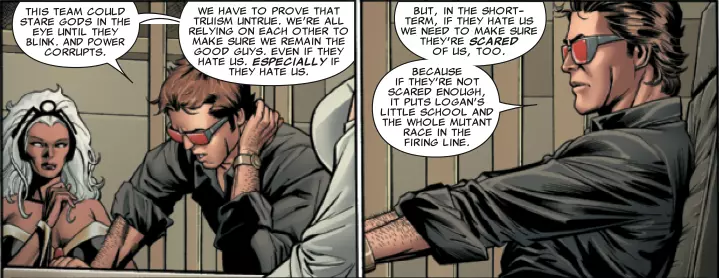

KG: Utopia is basically a state. It's not just a rock in the ocean. These people have faced intense persecution. The Sentinels are these genocide machines, these death camps on legs. This is why this matters. And it's about their survival... One line I use is that this team is a nuclear deterrent. This is a ridiculously powerful team, and mostly [former] X-Villains. No one believes that Iceman is going to destroy New York. Magneto, however...

CA: On the other side, we've got Wolverine set up now as the idealistic teacher/hero in Wolverine and the X-Men, which seems odd on a certain level because he was always the one X-Man who would totally kill people. And the X-Men don't kill people.

KG: Traditionally, the X-Men never kill people... I'm basically a pacifistic kind of guy, but Scott's very much, "Oh, I think we can kill people now." He's reimagined himself as a soldier, and he will kill people, but within sharp lines of engagement.

CA: Did you read that story in Rick Remender's Uncanny X-Force, where the team has to decide whether or not to kill the child version of Apocalypse? Because I feel like there were similar themes going on.

KG: That's the heart of it. If you look across the last few years of Marvel Comics, there's lots of interesting stories about the relationship between adults and children. In Journey into Mystery you have Kid Loki and this whole generational thing, and if you're looking for a theme for the larger Marvel metaverse I might say it's "generations." It might also be because a lot of the writers have had kids.

CA: We've seen Scott moving away from some of the traditional ideas of Professor Xavier's Dream, but I think a lot of the reasons for that have come out of what Xavier did to him. He was essentially a child soldier, and that informs a lot of what he's doing now.

KG: If you turn a boy into a paramilitary, you can't be surprised at what happens in 15 years time, I think.

CA: Magneto's on the team as well, and Scott's approach seems much more like the sort of philosophy that we've seen from Magneto in the past.

KG: Batman's been hanging people out of windows for forty years. The reason he still remains a hero is that he doesn't drop them. If we accept the concept of threats and vigilantism there, it is really different if rather than doing it against poor, random people in the street we use the threat of force against governments who persecute people? Is that a moral problem? Totally. Uncanny is a really big scale superhero comic, but it's murky. It really could go wrong.

CA: Do you mean it could go wrong for the characters, or on a more meta level with your actual writing?

KG: Both. In the context of the story, they're playing up to the worst fears of mutants to give mutants enough time to resolve their situation. There's a line in the first issue where Scott says, "What's the difference between Iraq and North Korea?" And it's that Iraq didn't have weapons of mass destruction. But he's comparing them to North Korea and Iraq! And they're called the Extinction team. I'm very explicitly increasing the sense that Utopia is a rogue state.

CA: You've talked about Colossus before, and how he took on the mantle of the Juggernaut because he is a character who is willing to sacrifice himself, and being willing to become something that dark is the greatest sacrifice he can make. Is this something similar?

KG: Yes, and I don't think people quite get what a big thing Colossus has done to himself. The idea of the Juggernaut has been around so long it's almost like it's just another superhero. It's not. It's demonic possession, like The Exorcist, and I'm trying to bring that stuff more to the fore. To me, the X-Men are these heroic action fictions with these enormous threats made meaningful by the soap opera. I want it to feel like an X-Men book. It has to feel like an X-Men book.

I generally believe heroism is about sacrifice. If it doesn't cost you anything, it might as well be holding the door open, and that's not heroism; that's politeness. Superman saving the world is basically politeness, as far as I can see. It doesn't cost him anything. I know that's the opposite of the Grant Morrison position, which -- I guess -- is the reason I'm writing X-Men. They've always meant more to me than Superman. You find character by their decisions in difficult situations, and that's the energy that drives the X-Men. Plus the belief in a future worth fighting for... I think you can look at the enormous amount of post-apocalyptic futures [in fiction] at the moment, which are fundamentally throwing your hands up in the air and giving up, and it's indulgent. There's an indulgence in post-apocalyptic fiction.

CA: Well, it's often infused with this feeling of giving up. It's actually easier to give up than it is to keep fighting against enormous odds, no matter how tired you are.

KG: As a reader, one thing that always moved me -- an easy way to make me cry is completely and utterly flawed and doomed heroism. If I even think about the scene in We3 with Bandit and the Doctor... I'm tearing up right now. It entirely kills me.

CA: The idea of heroism requiring bravery seems to come back to this idea of of fear that you keep circling. Why is the concept of fear so interesting to you?

KG: It's something that's always been in the X-Men... The intimidatory nature of fear, and could this curse be a blessing? For all the X-Men's most defining characters, the power is also the curse. So if the curse of the X-Men is being feared, can we use that?

CA: We've seen the X-Men engage in PR moments in the past in hopes of gaining public trust and support by saving people. Are we going to see incidents that are the reverse of that?

KG: There's specifically a note in the first arc where they do something incredibly heroic and powerful, and the implicit difference between when the Fantastic Four does something this and when the X-Men do this becomes quite clear. Even when they're being heroic -- if the X-Men sent Galactus packing, I don't think they'd be cheered like the Fantastic Four, just because they're the X-Men. You've got Scott going, "We're always going to be reported badly; is there any way to make that a good thing?" In the Cold War, America wasn't particularly fond of the U.S.S.R., but they didn't particularly want to to start a war with them either. That's the heart of what makes my run unusual, I think.

CA: You're writing a new #1 issue, and obviously that's intended to bring in new readers and lapsed readers; what's your pitch for those people who might be coming in without any sense of the recent history?

KG: Every first issue needs to be its own pitch. You've got a lot of eyeballs on it. One of most regular questions in my interviews about the issue has been, "Did feel intimidated doing a new #1?" And actually, no I don't. I felt intimidated in the last issue, because that was like trying to put a thematic bow on 40 years of history and the characters and the work that's been done on them. Doing the first issue is just a lot of work. There are so many craft-based problems: introducing the concept of mutants, the X-Men as they currently are, all the characters and powers, San Francisco -- oh, and the villain. There's so much you've got to get into it... Previously I chose to focus each arc on a number of characters... I introduce each one and why you care about them. Or hate them.

For example, in Fear Itself I actually spent quite a lot of time on Juggernaut in the first issue. I could have introduced him in one page, but I didn't want him to show up and assume that everyone's been reading him for 50 years so they'll know, "Oh, it's Juggernaut, we're in trouble now." No, you can't assume that. I want my wife to be able to read this. That's the absolute, complete minimum we should be doing. That's what I'm bringing forward into the relaunch I can't change where comics are or digital distribution or anything like that, but I can at least try to make a comic that people can actually read... We ought to make people want to read all the books, and we're in a shared universe; but at the same time, if you're only buying Uncanny X-Men it's completely understandable.

CA: You used to do music and video game journalism. Do you miss it now that you're full-time in comics?

KG: A little bit. As a working creator there's a limitation... You don't want to pick fights, but there's stuff where if you start doing critical theory, it becomes picking fights. So that's what I kind of miss. I still do bits of games criticism. I do little bits of music journalism. Give me another 12 hours in the day and I'd still be doing it. I'm very into to the contextualization of culture. I talk to my own critics not to say, "You've got my view wrong!" but to generally say thank you. I'm always very pleased when I see someone hammer out 10,000 words on something I wrote... Being a journalist for as long as I was -- you write a review, post it, and within hours you have 800 people calling you a c*nt just for having an opinion and giving something an 8/10 rather than a 9/10. And that makes you tough. I came into this knowing that people would hate me. Being an X-Men writer is worryingly like being the X-Men at times like that. Especially with the X-Men, you're never going to make everyone happy because there are so many characters and so many favorites. You just try to tell a good story and hopefully it'll go over well.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Bond After Brexit: Kieron Gillen Declassifies ‘James Bond: Service’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Service_McKelvie-feat.jpeg?w=980&q=75)

![You, Me, Dancing: The Impact Of Gillen, McKelvie And Wilson’s ‘Phonogram’ [Music Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/01/Phonogram-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)