Pretend They’re People: The Fifty-Year-Old Answer to Marvel’s Diversity Problem

Writing a book on feminism in popular culture requires a surprising amount of research. Most days you’ll find me reading in a library or a café, propping open books with my cell phone and copying out quotations. Eventually I’ll turn the whole mess into another chapter of my rapidly growing study on the positive development of female superheroes in Marvel comics.

It’s not a position often taken; most studies of mainstream comics denote how the objectification of women and the presence of antiquated stereotypes remain more consistent than acts of transgression against them. Comics continue to fail the Bechdel test, and to put women in refrigerators.

It remains a bleak time for the female comic audience.

And the same is true for the minority or LGBTQ reader. The recent debacle with Hercules is merely the latest of Marvel’s many ghastly faux pas; for every two steps forward, it seems to take two steps back: it publishes more female titles only to end the majority of them with Secret Wars, and it tantalizes us with Hercules only to promote the status quo inside of continuity.

It is easy to lose faith in the publisher’s ability to reform from within, when — with the exception of recent works like Ms. Marvel — much of the evidence suggests ineptitude.

But — and I hope you’re paying attention here — Marvel has had the key to equal, positive representation for over fifty years now.

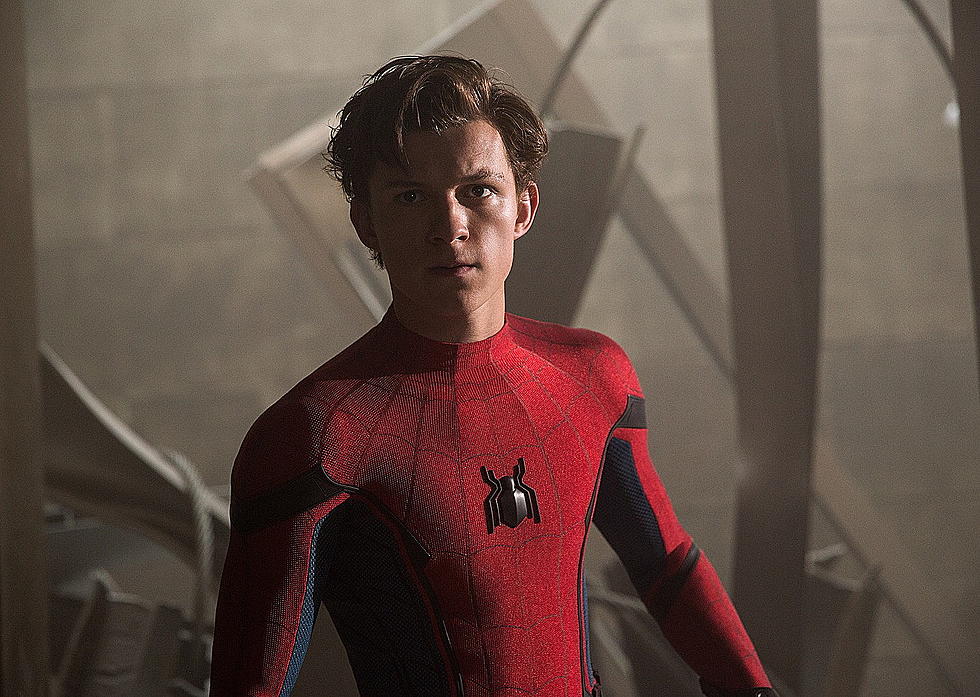

I stumbled across the answer while reading Paul Lopes’ Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book, published back in 2009. Like many things Marvel, the solution comes straight from Stan Lee. In Demanding Respect, Lopes explains how Lee created an entirely new breed of superheroes in the 1960s, including the amazing Spider-Man.

No longer were superheroes merely two-dimensional depictions of American perfection; suddenly they were allowed to have, as Lee described in a 1971 interview with the New York Times, “New ways of talking, hangups, introspection and brooding.”

They became humanized, exhibiting idiosyncratic identities that were brand new to the genre. “I talked to Jack Kirby about it,” explained Lee later in the interview. “I said, ‘Let’s let them not always get along well; let’s let them have arguments'.” For the first time ever; “Let’s let them talk like real people and react like real people.”

Lee humanized the superhero of the 60s, and Marvel never looked back.

This is the answer. This is how Marvel can write better, more inclusive stories.

In fact, an ideology just like Stan Lee’s is already having a significant impact on improving the representation of women in Marvel’s comics. Two months ago Kelly Sue DeConnick said something remarkably similar in a “Thank You” edition of the Women of Marvel podcast. (Episode 52, June 2015.)

Sana Amanat, editor of the exceptional Ms. Marvel, had turned the conversation in the direction of problematic female characterization. “When people ask that question ... obviously that question that we all hate, ‘How do you write a good, strong, female character?', you just want to shake the person,” she said. Although the question may be well-intentioned, it denotes a powerful and consistent misconception within the genre.

“My pat answer,” quipped DeConnick, “is, ‘Pretend they’re people’.”

It is jarring when you consider her words as they relate to women, and as they could be related to other marginalized racial and sexual groups. “Pretend” they are people? It seems obvious that we ought to treat every individual as a person, but the field remains ripe with double standards and hypocrisy, not to mention tactics that perpetuate heteronormative power by putting transgressors “outside of continuity.”

(If this tactic interests you --- or enrages you --- consider reading Michael Goodrum’s article “’Oh C’mon, Those Stories Can’t Count in Continuity!’: Squirrel Girl and the Problem of Female Power,” which was published in Studies in Comics Volume 5 #1. It explores the way that Marvel used a similar tactic with Squirrel Girl originally, and theorizes that this is yet another way that Marvel has kept the majority of power — within continuity — in male hands.)

The American male — particularly the white hetereosexual male — is too often treated as a sort of cultural “norm.” In relation, any female, minority, or LGBTQ person becomes an 'other'.

“My husband is also a comic book writer and he’s never once been asked, ‘How do you write a strong male character?’” said DeConnick.

“Hercules' sexuality was not something [Dan Abnett] considered,” Axel Alonso told Comic Book Resources in a recent interview in light of the controversy over presenting the character as straight. “[H]e was unaware of any hints out there that Hercules was anything other than heterosexual.” Sound familiar?

The message here is that a lack of conversation about Hercules’ sexual history made writers assume that he was heterosexual. This should be as alarming as the fact that undescribed racial identity has been assumed to indicate whiteness.

(Rachel Kinney studies this phenomenon in her article “‘But I Don’t See Race’: Teaching Popular Culture and Racial Formation. Although it’s hard to misrepresent a racial identity in sequential art, Kinney depicts how often readers assume characters in literature are white when they may not be. This is a form of racism.)

Why do we normalize the hetereosexual white male and segregate women, racial, and sexual minorities?

I don’t know, but we shouldn’t. And Lee’s fifty-year-old assertion is the perfect predecessor to inform equalization today. We are already applying it to female superheroes; now we have to treat all of our characters like real people, whatever type of people they may be.

“The thing is that there are as many expressions of femininity as there are women,” said DeConnick in the same interview. “And they will know that she is a woman because she’s a woman. Don’t worry about it. Write about what she wants, write about what is important to her.” She treats all of her characters like people, and the effectiveness of her writing reflects the effectiveness of this approach.

Alonso says that the Marvel catalog is already set to diversify, and hopefully the publisher will move forward aware; Marvel has always had the answer, straight from Lee’s mouth: “Let’s make them talk like real people and react like real people,” rather than, in DeConnick's words, like pin-ups, porn stars, stereotypes or men “in drag.”

Let’s do a better job of 'pretending' they’re people, and — for god’s sake — let’s include them in the main Marvel Universe.

More From ComicsAlliance