![Surrender Yourself To The Siren Song Of Mark Siegel’s ‘Sailor Twain’ [Review]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2012/11/sailortwainognmain.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Surrender Yourself To The Siren Song Of Mark Siegel’s ‘Sailor Twain’ [Review]

In the late 19th century, about the time during which Mark Siegel's new graphic novel Sailor Twain, or, The Mermaid of The Hudson is set, American critics and thinkers started talking about "the Great American Novel," in response to England's dominance of English-language literature.

The Great American Novel, it was believed, would be one that captured and contained the spirit of the country in terms of its craft, its theme and its subject matter. Over the decades, plenty of novels have been identified as Great American Novels (and candidates for the Great American Novel), books that have become part of our literary canon, including Moby Dick, The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, whose author shares a surname with the title character of Siegel's book.

Could the Great American Novel actually be a Great American Graphic Novel...? The argument could be made for Siegel's Sailor Twain. In size and scope and narrative structure, it's truly a novel, albeit in comics rather than prose. It is comics, a truly American story-telling form that in the 21st century is almost as mainstreamed as prose fiction. Its themes and subject matter are various, and will take a bit more explanation, but include cultural clashes and synthesis of other, foreign cultures into something new, the tensions between sexual temptation and creative pursuits on the one hand and societal constructs and duty on the other and the struggle for equality between the genders.

In size and scope and narrative structure, it's truly a novel, albeit in comics rather than prose. It is comics, a truly American story-telling form that in the 21st century is almost as mainstreamed as prose fiction. Its themes and subject matter are various, and will take a bit more explanation, but include cultural clashes and synthesis of other, foreign cultures into something new, the tensions between sexual temptation and creative pursuits on the one hand and societal constructs and duty on the other and the struggle for equality between the genders.

And the setting and surface details are about as American as can be.

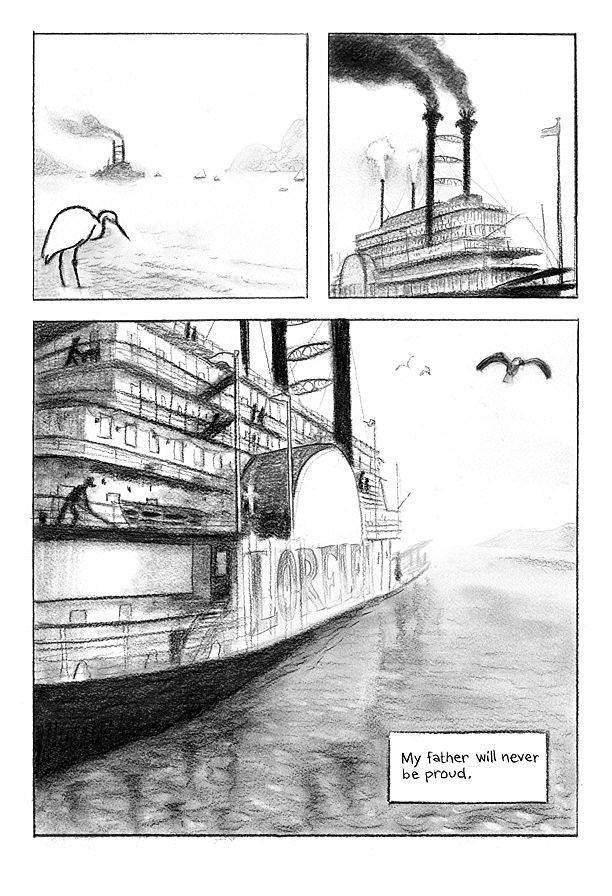

In 1887, the steamboat Lorelei travels up and down the Hudson River, under the command of its dutiful, punctual, professional Captain Twain ("That's not his real-" he begins to explain, when a passenger asks him if he's related to the writer, although a couple of mysterious stowaways on the ship taunt him by leaving out copies of Huckleberry Finn). This Twain would also prefer to be a writer than work aboard a riverboat, although his medium is poetry, and he had to put it on the back-burner while he worked the river, earning money to support his wife, afflicted with a malady that keeps her in a wheel chair.

Also aboard the ship is its owner Lafayette, who recently lost his brother and more recently still began to act rather mysteriously, pursuing a half-dozen love interests with a feverish intensity, dropping letters in bottles into the river when he thinks no one is watching and exchanging letters on the subject of mermaids with a C. G. Beaverton, a reclusive American writer no one has ever seen in person.

When Twain finds a badly wounded mermaid in the river, and secrets it in his cabin in order to nurse it back to health-and, in exchange, she magically inspires his poetry-he gradually begins to unravel the mystery of what became of Lafayette's brother, why Lafayette has been behaving the way he has and what the two men share in common.

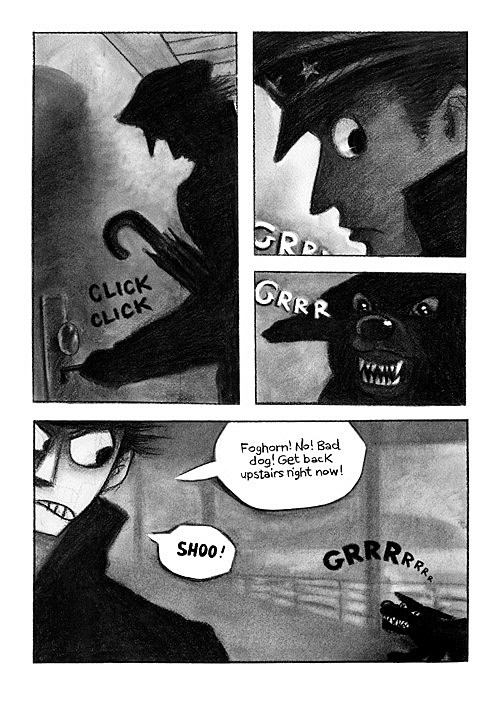

Siegel's black-and-white artwork is rendered not with the traditional pencil and ink of most comics and graphic novels, but in charcoal, making for thick lines and a cloudy, gauzy look perfect for a dark and mysterious river, the coal-smudged crew of a 19th century steamship, and the murky, stormy goings-on of the Lorelei and the lives of the men upon it. Additionally, the medium allows for whites to appear particularly luminescent, by virtue of the rich and layered darkness of the blacks (The pale skin of Lafayatte's seventh lover, for example, appears to glow in a darkened cabin).

His character designs tend toward the cartoonish, with his Twain having huge, saucer-like eyes and a triangle nose that give his face a Muppet-like appearance and his Lafayatee a big, long, Cyrano de Bergerac-like nose. Sometimes exaggerated shapes aside, these characters' bodies and clothing are rendered realistically, as is the meticulously created steamship and the detail-heavy (and apparently quite thoroughly researched) settings.

His character designs tend toward the cartoonish, with his Twain having huge, saucer-like eyes and a triangle nose that give his face a Muppet-like appearance and his Lafayatee a big, long, Cyrano de Bergerac-like nose. Sometimes exaggerated shapes aside, these characters' bodies and clothing are rendered realistically, as is the meticulously created steamship and the detail-heavy (and apparently quite thoroughly researched) settings.

The mermaid has a story, of course, a story presented as a story within the story, and it has the feel of a genuine mythology, although this being the still-young, barely-a-century-old United States of America, it is of course an invented mythology. But so thoroughly has Siegel created and recreated his cast and their era, that it feels and reads as real as anything else in the book.

Invented mythology, the filling-in of cultural needs with a new rituals and beliefs based on old ones bur tailor-made to suit the new and young country specifically, is but one more particularly American trait of Siegel's incredible book.

I suppose ultimately it will be up to future critics, literary scholars and canon-keepers to decide if graphic novels are up for consideration when it comes to the title of The Great American Novel. For now, I feel it's safe to, at the very least, declare Siegel's graphic novel both American and Great with a capital "G."

More From ComicsAlliance

![We Read To Challenge Ourselves: An Interview With Mariko Tamaki [Pride Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/06/PrideWeek-Tamaki.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Love, Art, Memory, And Reality: Scott McCloud Discusses ‘The Sculptor’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2015/01/McCloudSculptorHeader.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![‘Zita The Spacegirl’ Creator Ben Hatke On Writing For Young Readers (And Not Boring Their Parents) [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2014/12/HatkeHeader.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Comics, Prose, And Virtual Realities: Cory Doctorow Discusses ‘In Real Life’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2014/11/irl-hed.jpg?w=980&q=75)