![‘Casanova: Avaritia’ #2 Hits Like a Punch to the Stomach [Review]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2011/10/casanova-gabrielba-personal-top-1318311799.png?w=980&q=75)

‘Casanova: Avaritia’ #2 Hits Like a Punch to the Stomach [Review]

It's tough to write about Casanova: Avaritia #2. I liked the first issue, particularly a great innovation regarding the lettering and thought balloons, but the second issue was just... tremendous. I enjoyed the art just as much as ever, if not more so, but this issue felt like it was Matt Fraction's time to shine. And shine he did, with a story that featured a man who was more okay with murdering trillions than he is with murdering one person over and over, several variations on a single scenario that come with the impact of shotgun blasts, wanton murder, and a game-changing revelation that somehow ended up being about the creative process -- a final punch to the stomach that really and truly impressed me. Where do you start talking about Avaritia #2, and how do you end without ignoring some vital aspect of the book? To be honest, I have no idea. I can't.

So I won't. With genuine apologies to the (seriously fantastic, and possibly unbeatable) art team of Casanova, I'd like to talk about Matt Fraction's contributions to a fantastic single issue.

Casanova Quinn went from super-spy to the greatest murderer humanity ever devised. After the blood-soaked events of Casanova: Gula, Cass has been tasked with one job: eliminating from the timestream any trace of Newman Xeno, leader of W.A.S.T.E. (a terrorist organization that stands for... "We're all so terribly excited," perhaps, or maybe it's "We always start things early"). Xeno is public enemy numbers one through infinity, a villain bad enough that if you happen to take out an entire timeline while getting rid of him, it's worth the cost. He's that big of a deal, and those other timelines aren't real like we are, are they? No. They are not. They're hypothetical. Which is fortunate, because no one knows who Newman Xeno really is, so in order to get to him you really do have to murder entire timelines.

As a result, Cass's new job is being dropped into a new timeline, locating a small device, and pulling that device's trigger. The result? A spatiotemporal holocaust. Billions of lives are snuffed out in one shot, and then Casanova returns home. Repeat this process over and over again and you have a body count in the trillions. Up to a certain level, that's easy. Casanova's victims are mostly faceless in their trillions.

Past that point, which is where we find Casanova at the beginning of Avaritia #1, and the unthinkable number of dead that Casanova has racked up is high enough to have its own gravity. That wears on him, until his devil-may-care attitude twists into something else. The exuberance that he once had is gone, replaced by poison, and he's venting nihilism hardcore.

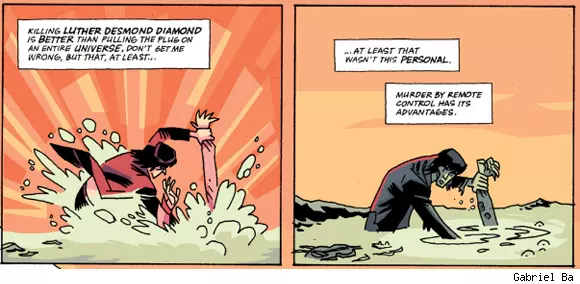

Between #1 and #2, however, Casanova's mission changes. He discovers Xeno's identity, a musician named Luther Desmond Diamond, and the new objective is to murder Diamond in every possible timeline, just in case. The scale is smaller than the destruction of worlds, but the toll it takes on Casanova is somehow larger. He laments the personal nature of the murders. You can talk yourself out of faceless deaths. But killing one man over and over and over? That isn't abstract. It's too real. And the fact that Diamond's essentially helpless -- that doesn't make it any better.

The shift between the abstract and the concrete is an interesting one, in part because of the way it changes how Casanova views his job. It makes his feelings worse, but the continual pursuit of one victim over and over has a funny side effect. Spend enough time with someone and eventually, you'll get to like them. Spend enough time with someone while preparing to murder them? That attraction will get all tangled up with guilt and result in something... different.

Ages ago, Grant Morrison and Sean Phillips Steve Parkhouse (sorry!) created a comic called Best Man Fall. It was in the first volume of The Invisibles, and it concerned the life of a single guard. The guard died in the first issue of the series. He was cannon fodder, the type of nameless character who gets killed and made fun of by the hero. Best Man Fall spun the camera from the hero to the guard, and we saw his life. We saw his wife, his childhood, his fears, and his hopes. By altering the point of view, Morrison and Phillips added depth to the series and forced the reader to confront how they look at cannon fodder in stories like these. On one level, it's okay, because they're faceless. But when you zoom in, everyone has a face.

Fraction and Bá took the idea of a Best Man Fall and applied it to Casanova, rather than us. Over the course of the issue, Casanova repeatedly interacts with Diamond. The contact humanizes Diamond for Cass, and he goes through an experience like the reader does in Best Man Fall. The difference is that Casanova Quinn is fictional, and can therefore do something about the cycle of pain.

Love The Ones You Hurt

"Personal" is a fuzzy word when applied to comics. Sometimes it simply means work that's emotional -- a Hulk story that's about how sad he is, rather than how smashy he is. It also applies to stories that are smaller in some way; Spider-Man may protect a child from bullies in personal stories, rather than protecting Mary Jane from the Green Goblin. There are a few more definitions of "person: in comics, but it is usually applied to stories that seem to feature either some sort of explicit connection to the author's thoughts or are semi-autobiographical.

It's tempting to try to map Matt Fraction onto Casanova Quinn, and to be honest, it's pretty easy to do exactly that after some fairly reasonable conjecture, but that wouldn't give you a full picture of the comic. Fraction clearly bled all over these pages, and while he's copped to a few lines in the issue as being explicitly autobiographical, it's more interesting to look at how Fraction's experiences shaped the comic. In other words: Mind-reading is pointless, but reading tea leaves? Much more interesting.

Matt Fraction is a creative guy. He works in a creative industry creating new stories with old characters. He's one of the top writers at Marvel right now, but more important than all of that is the fact that he's a writer. So when I realized that there was an undercurrent of creativity (expressed via dreams, comic books, stories, interviews, music, and more) bubbling throughout this issue and climaxing toward the end, I sat up and paid attention.

Luther Desmond Diamond is a creative guy. No matter the timeline, it seems like he's making music, writing comics, or something. And toward the end, he's given an organic chance to talk about his creative process. When he does so, he explains how he writes songs through an elaborate metaphor. He talks about he's no good at the one thing he's actually good at, so he lives the stereotypical rock star life until the art comes. "The art will come later or I'll just f---ing kill myself I guess," he says.

This is personal. Personal, for me, works best when it's expressing something that is specific to a single person, but general enough to be easy to relate to. Anyone who is good at something -- whether that something is drawing comics or fixing up cars -- knows what it feels like to feel bad at it. The best have to sit and stare at a blank page, or an engine that's making a funny noise for no reason, until they figure out how to approach the problem. It's a slippery goal to hit, and the fact that you're so good at it makes you feel even more acutely like you're so bad at it. If you really were that good, you could solve it instantly. Bang out that hit song in twenty minutes, diagnose the engine knock on your first try, and write your book in fifty thousand word bursts. But no, that's not how creativity works. That would be nice, but: no.

Casanova: Avaritia, and really Casanova in general, is a very big comic. There are a lot of ideas in here, from Kirby and Steranko-esque spy organizations to high technology to homages to cool movies to outright adaptations of songs. It's pleasingly dense, but none of that would matter if you couldn't relate to any of the characters, or at least recognize them as being rooted in real life. Luke Skywalker's a farm boy in over his head. Spider-Man is you. There's always going to be that core that we can relate to. That's why we believe in them and enjoy the stories. So for Fraction to drop this white hot rock of "Yeah, I am a human being, after all" into the story for Newman Xeno... well, that's huge.

Avaritia #2 is a stunning issue from top to bottom. The art clicks on all cylinders, from Casanova's earnest expression and black eyes late in the book to the shoot-out at the comic convention. The lettering and writing were just as good as ever. But the way it shifts into being even more personal than usual, on several levels, is impressive.

Buy it digitally or at your local comic shop. Either-or is good, but trust me: you want to be reading this series.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Touch Me, Touch Me: The ‘Sex Criminals’ Mixtape [Love & Sex Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/02/Sex-Criminals-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![All The Creator Spotlight Panels To Check Out At San Diego Comic Con [SDCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/07/Creator-Spotlight-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)