Ask Chris #109: The Movie Industry’s Kill-Happy Super-Heroes

Here at ComicsAlliance, we value our readership and are always open to what the masses of internet readers have to say. That's why every week, Senior Writer Chris Sims puts his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

Q: Why is it when superheroes are translated to movies or TV, "no killing" seems to be the first thing out the window? -- @jason1749

A: I've reviewed a lot of comic book movies here at ComicsAlliance, and the casual attitude towards super-heroes killing is one of the things that always gets on my nerves about the translation to movies. It's hard for me to get past even in a movie like Captain America where it's arguably justified by the war-time setting, and for Batman '89 or Superman II, it's the breaking point that completely ruins the movie.

As for why, it really just comes right down to the differences between comics and movies, and how they've evolved in pop culture. I think the problem has its root in the fact that The Hero With a Code Against Killing is really only a common element in super-hero comics. In other media, adventure stories tend to be a lot less strict about their heroes' morality. Even the pulps, from which super-hero comics were directly descended, were defined by characters who were prone to blowing away their enemies with smoking pistols and the occasional zeppelin.

I think the problem has its root in the fact that The Hero With a Code Against Killing is really only a common element in super-hero comics. In other media, adventure stories tend to be a lot less strict about their heroes' morality. Even the pulps, from which super-hero comics were directly descended, were defined by characters who were prone to blowing away their enemies with smoking pistols and the occasional zeppelin.

But even though the pulps were a profound influence, comics evolved differently. I've gone into this before with a specific focus on Batman (surprise!), who essentially started out as a Bob Kane and Bill Finger's fan-fiction for the Shadow. The dark costume, the millionaire secret identity and the pistols that he packed in those early appearances are all there, to the point where Clark Savage (The Man of Bronze!) and his Fortress of Solitude are actually not the most blatantly lifted elements that formed the foundations of the DC Universe. As comics moved into their own direction and the heroes solidified into unique creations, though, one of the elements that came to define the genre was the code against killing.

A lot of people who haven't actually read a lot of Golden Age super-hero comics tend to assume this was the sinister, meddling influence of the Comics Code. That was certainly a factor later on, but it's not the case at the beginning. Batman's change from gun-toting vigilante to non-killing super-hero actually hit the comics a full ten years before the Code was put into place. It's more likely that it was just a shrewd business move to appeal to a younger audience -- and to reassure the parents who were actually buying these things that their characters were solid, upstanding role models and not a filthy commie plot to corrupt America's youth.

There's another good reason for it, too. Unlike most other genres in other media, super-hero comics aren't generally designed to be finite. Even when they are, that's no guarantee that someone won't eventually try to wring a little more cash out of them by exploiting the property anyway, but that's something you can read about elsewhere. The point is, a successful comic isn't usually supposed to end. Unless it's specifically built with an ending in mind, it's supposed to keep going for as long as people want to pay money to read it. And when your protagonist kills his enemies, it's pretty difficult to have a recurring villain.

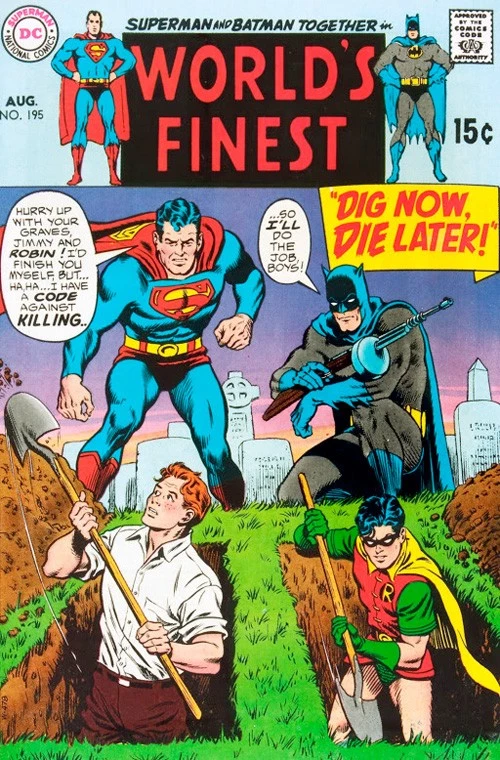

Regardless of why it was introduced, comics embraced the idea of heroes that didn't kill and made it work phenomenally well. Batman's entire story evolved over the past 70 years to be a rejection of and a battle against murder, and he's not the only one to have that sort of development. It's a particularly strong element of Superman's character as well, and it's one of the key factors that makes him heroic. Even if you dress him up in a friendly costume and give him a nice smile, the idea of an all-powerful alien being coming to Earth and throwing his weight around is inherently frightening. If he kills people -- even bad people -- then that sets him up as someone who considers himself to be above us, willing to make the decision to dole out punishment as he deems necessary, and he becomes downright terrifying. He becomes an executioner, something to be feared. But if his character is built around a rejection of killing, a code that shows that he respects life, that immediately recasts him as a protector and a guardian, someone whose presence is comforting and reassuring.

Once it was a part of Batman and Superman, it became a standard part of the genre. Most of the more violent characters of the Golden Age didn't last, and the ones that did were toned down by the Comics Code. It was even refined for the Marvel heroes when they hit in the '60s. Spider-Man is, after all, a character who is explicitly defined by the desire to use his power responsibly to keep people from being killed. I mean, there's not even a metaphor in that one; it's written right there on the page. Even later, when protagonists who did kill were introduced, like the Punisher and Wolverine, they were often defined by being exceptions to that rule.

Here's the thing, though: That's only true in comics.

Movies are a completely different beast. For one thing, they're built differently. Even the ones that are made with a sequel (or trilogy or saga or whatever) in mind tend to be geared towards telling a complete story in and of themselves. They're crafted to include a sense of finality that leaves the audience satisfied, and -- unless the story involves ghosts and the busting thereof -- it doesn't get much more final than death.

That's especially true of Action Movies, and that's where you really hit the snag. Even now, when Batman and the Avengers are making literal billions of dollars at the box office, super-heroes aren't as defined as a film genre as they are in comics. Instead, they're just a subset of the Action Movie genre, which has its own language and conventions and tropes, just like super-hero comics do. And part of that language is that, more often than not, the bad guys die at the end.

A lot of times, that's how you know the movie's over: The good guys win because the bad guys die, and usually a lot of smaller, less important bad guys die along the way. It's not a bad thing, either. For me, it's every bit as ludicrous to imagine Batman gunning down his enemies as it is to imagine John McClane not killing Hans Gruber and his band of exceptional thieves. Indiana Jones is no less heroic because he shoots that dude with the sword in the marketplace. There's nothing about their actions that conflicts with how they're created, and the world in which they live.

The problem is that that's not how most super-heroes are built. It's a world that they're brought into, and more often than not it's by people who want to make a action movie rather than a super-hero story. That's also why elements are changed in the name of making things more appealing to a wider audience, which has been trained to recognize the standard elements of an action movie rather than the standard elements of a super-hero comic. And that, of course, usually just means dumbing things down and trying to make things that were designed for a never-ending series fit into a very finite structure. That's why you get stuff like the Joker being the guy who killed Batman's parents in Batman '89. In an Action Movie, the hero has a personal vendetta that can only be settled by killing his enemy, so Batman and the Joker end up with a relationship that's exactly like the one John Matrix and Bennett have in Commando.

Still Jeph Loeb's finest work, by the way.

With all that said, it's not always a bad thing when a super-hero kills in a movie. The one movie that really does it well? Iron Man.

I really love the scene where Tony Stark builds his armor and goes to hunt down the terrorists who imprisoned him at the beginning of the film, because it manages to work in the context of both the traditional Action Movie and the traditional Super-Hero Story. It's a great bit of classic revenge film thrown in there, the culmination of Stark clawing his way out of being imprisoned and returning to overwhelm them with his technology, in the form of a machine that he built specifically to kill people. That's what the Iron Man armor is at that point, and why it's outfitted with face-seeking missiles. It's a very brutal, very personal conflict. In an action movie, this would be the climax.

But it's not. It happens right in the middle of the movie, because Tony Stark's story in that film isn't based around revenge. It's about his transition from being the kind of self-obsessed narcissist who wants revenge into being the kind of hero who will sacrifice himself for others. His journey isn't a quest for vengeance, it's becoming someone who wants something more than that.

What's really brilliant about this scene and the way Jon Favreau presents it is that we get there before Iron Man. We see these dudes raiding a village and taking kids away from their parents, so we have a context that casts them unequivocally as bad guys. But Tony Stark only has the context of his experience, and the fact that they're messing around with his stuff. At that point in the movie, he doesn't care about rescuing the civilians; it's just a nice coincidence that they happen to be in danger when he shows up to kill the bad guys. But at the end of that movie, we have a Tony Stark who actually can look beyond himself. That's how the story's told, and it works really well.

Unfortunately, most other super-hero movies don't have that level of craftsmanship behind them, and most other comic book characters aren't former weapons manufacturers who lend themselves pretty well to that concept. But hey, it's a start.

That's all we have for this week, but if you've got a question you'd like to see Chris tackle in a future column, just send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #AskChris, or send an email to chris@comicsalliance.com with [Ask Chris] in the subject line!

More From ComicsAlliance