Ask Chris #112: Where Were You On The Night Batman Was Killed?

Here at ComicsAlliance, we value our readership and are always open to what the masses of Internet readers have to say. That's why every week, Senior Writer Chris Sims puts his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

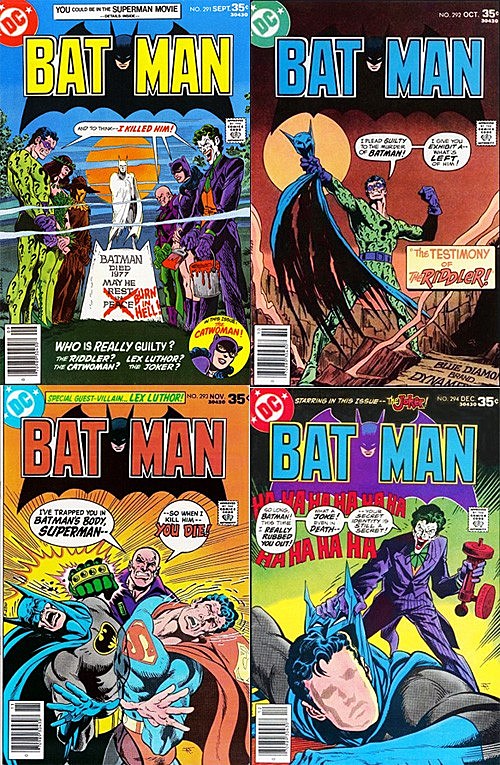

Q: What's the story behind the cool cover to Batman #291? -- @phillyradiogeek

A: Normally, I prefer to take on questions that allow me to yammer about themes and elements of the fictional tapestry and why Batman rules to questions about the events of a specific issue, but this is an interesting case for two reasons. For one, while it's not an important story in the context of the character, it is a pretty significant early example of how comic book storytelling developed. And for another, you're right: that cover is awesome.If you're not familiar with the issue, here it is in all its Jim Aparo glory:

It's a pretty striking image -- so striking, in fact, that DC used it as the cover of the relatively recent Strange Deaths of Batman paperback, when it was reprinted in collection of stories where Batman did not in fact die as a tie-in to Batman's more recent non-death in Final Crisis. Uh, spoiler warning, I guess? I mean, I don't think anyone's going to be too shocked to find out that Batman didn't actually die in 1977, but you never know.

So considering that Batman doesn't die in pretty much every other Batman comic, what makes this one so interesting isn't the story, it's how that story is structured. "Where Were You On The Night Batman Was Killed," by David V. Reed, John Calnan and Tex Blaisdell kicks off in this issue as a four-part epic -- one of the earliest examples of the long-form, multi-issue story that would become the standard a few decades later.

It definitely wasn't the first. I've written before about how the modern long-form style of comic book storytelling has its roots back in what Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were doing on Fantastic Four, but this story was coming during a transitional period where that was becoming the standard for comics. Marvel's style of ongoing soap operatic adventures had revolutionized super-hero storytelling, and while DC had hung on to their classic Silver Age style of eight-pagers with the occasional "Three-Part Novel, Complete In This Issue" for a while, they were rapidly moving that way, especially in the Batman titles. In 1976, they even hired Marvel writer Steve Englehart, and while he worked on an awful lot of DC's titles, his run on Detective Comics with Marshall Rogers -- where they created an ongoing thread that tied a together a year's worth of stories -- is probably his most famous work.

"Where Were You," though, is a little different. Even though it's designed so that each part has a more-or-less complete story, they're all united by a highly focused theme that makes them a single story. But for David V. Reed, even this wasn't exactly brand new territory. The previous year Reed had written another multi-part story called "Underworld Olympics '76," in which a bunch of international crooks went to Gotham City and started competing in organized heists with points in order to determine who was the best at crime. Unsurprisingly, doing this in Batman's hometown didn't work out too well.

But while "Underworld Olympics" just feels like a longer version of a Silver Age story, "Where Were You" reads in a lot of ways like a blueprint for the modern event. It's built around the (alleged) death of a major character, all of his major villains are involved, there are guest stars, and it probably goes on a little longer than it should.

As for how it all works out, that's actually pretty interesting too.

The story opens with the premise that Batman has been killed -- which for 1977 is a pretty bold move -- and instead of being about tracking down the culprit so that they can be punished for their crime, the premise is that everyone wants to take credit for it because whoever can claim they killed Batman will be a pretty big deal. As a result, all of Batman's foes get together at a rich crook's estate so that they can hold a trial and determine who the real guilty party is.

As much difficulty as I have believing that Signalman is an "illustrious cut-throat"...

...that's a pretty great setup.

It's essentially a reverse murder mystery. Each suspect presents their story of how they killed Batman, and the prosecution -- played, of course, by Two-Face -- then finds the contradiction in their story that proves that they couldn't have been the actual killer. It's the same sort of detective story setup that we've seen, but shown in a way that adds and twists just enough to the existing formula to make it feel interesting, and provide some really cool moments where we see how each villain's opposition to (and hatred of) Batman is a little different. There's a lot of personality on display that makes for a great read.

Unfortunately, Calnan and Blaisdell aren't quite up to the task. They manage to pull out some really solid stuff from time to time, and I'm particularly fond of Catwoman's bereaved widow act in the first part....

...but they're remarkably inconsistent. Beautiful panels with great acting and detail are right next to stuff that looks like it was done as fast as humanly possible to meet a deadline, and the overall effect is jarring. If this story had been drawn by Aparo or Rogers or Ernie Chan, there's no doubt in my mind that it'd be remembered far more fondly as a classic of the era.

Also, Calnan and Blaisdell tend to give Batman these odd-looking bunnyrabbit ears that do him absolutely no favors.

They do have their moments, though, and so does Reed, especially in the third issue. The first two are formulaic to a fault, involving Catwoman and the Riddler both telling stories that hinge on a fact that they get wrong, like Catwoman claiming that she booted Batman off her floating jaguar cage and left him to drown, Titanic style, when in fact the wood that the cage is made of is too dense to float. But in that third one, Lex Luthor shows up, and things get awesome.

Luthor's story is great, largely because it's a Superman story that just happens to involve Batman: Using maser beams fired from space, he rips Superman's mind out of his body and puts it into Batman's obliterating Batman's mind in the process, and then takes advantage of Superman's disorientation to beat him to death with his bare hands. It's brutal stuff that's a great reminder of how Lex combines his scientific knowledge with that base, jealous savagery born from his hate.

And rather than being based on an obscure factoid, the "solution" to Lex's story is actually a twist in the classic style: Superman and Batman just switched places and made Lex think he was winning while they were busy laughing their asses off at him:

The expressions in that panel, Superman barely keeping himself from cracking up while Sweaty Lex works so hard to do some killin'? Some of Calnan and Blaisdell's best work.

The other thing that makes that issue great? The outfit Lex wears to the trial:

Son is fierce.

I mean, there's also the fact that Lex considers doing the impossible and actually murdering Batman to just be an insignificant consequence of his real plan. That's the perfect summary of his character: for him, it's entirely about beating Superman, and if he has to make "Kill Batman" step one of that plan, then by God, he's going to do it. Mostly, though, it's the outfit.

Needless to say, the person actually did commit the murder is the Joker, needlesser to say is that the victim wasn't actually Batman at all, and needleast to say, Two-Face is actually Batman in disguise. So why the bizarre, extremely improbable (even for Batman) facade? It's all revealed in the fourth issue, where things actually get a little disturbing.

The way it goes down is that the Joker's getting ready to pull off some crime when -- due to the insanely high crime rate in Gotham City -- Batman stops another, completely unrelated crime in the exact same place, without ever noticing that the Joker's hiding nearby watching it. The next night, the Joker goes back to finish his job, only to find that Batman made it there before him. Then, the Joker manages to win the ensuing fight, and then he melts Batman's face.

It's shockingly graphic and, if you happened to be a kid reading Batman comics at the time, I can see it being genuinely terrifying. And on that front, it actually goes hand-in-hand with what follows.

But since that's not Batman, the question is who exactly that was, and it turns out that that's what prompted the entire story. With all of the ersatz Batman's identifying features eliminated, the only way to find the killer was to pretend that it was the real Batman, and prompt whoever the killer was into showing himself instead of letting someone else take the credit. Hence, the false report of Batman's death, the trial, and Batman's dedication to making sure he got the actual killer.

And the reason he does all this is that it's very personal:

All of that stuff, the price of Batman's heroism, the guilt that he feels for being personally responsible for the victim showing up at the scene of one of his exploits, the lengths to which he's willing to go to make sure that this person isn't just another (literally) faceless victim, the desire to make sure he has the right killer -- they're all very modern ideas. This story may not be as well-known as anything by Englehart and Rogers or O'Neil and Adams, but it's just as much of a turning point in how Batman was presented. There's a transition even in the story itself, from the simple whodunnit format of the first two stories to the Silver Age grandeur of Lex Luthor's issue, to the creepy, horrifying and exaggerated scenes of the Joker.

So that's the story behind the cool cover, and like I said, it's a nice example of how storytelling was evolving.

Unless, of course, you meant that you wanted the story behind the Superman movie contest, in which case -- as Matt Wilson was kind enough to point out -- the guys who won ended up playing football players at Smallville High.

That's all we have for this week, but if you've got a question you'd like to see Chris tackle in a future column, just send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #AskChris, or send an email to chris@comicsalliance.com with [Ask Chris] in the subject line!

More From ComicsAlliance

![Bizarro Back Issues: Beware The Dragon God! (Oh Don’t Worry, It’s An Octopus) (1981) [Fantasy Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/10/Spectre01.jpg?w=980&q=75)