Brian K. Vaughan And The Ongoing Story Of Post-9/11 America

In common with a fairly significant chunk of the comics community, Brian K. Vaughan was in New York on September 11th, 2001, and witnessed the tragic events of that day first-hand. Sublimating his experiences into his art, Vaughan penned Ex Machina, a modern masterpiece that used an alternate version of 9/11 to explore America's relationships with its heroes. But just as the long-term effects of September 11th are still palpable, Vaughan has continued to explore the anxieties of post-9/11 American throughout his work.

If I were asked to make a list of the ten best debut issues of all time, Ex Machina #1 would probably be near the top. It's one of those comics that grabs you right off the bat with the cleverness and possibility of the concept -- a retired superhero turned Mayor of New York City -- delivered with an intriguing structure, super-sharp dialogue, characters with strong points-of-view, and of course the muscular elegance of Tony Harris's inimitable Art Deco superheroics.

What really nails the impact of that first issue, though, is the last page.

That final, jarring image shows the World Trade Center re-claimed from history; half-alive, with one tower stubbornly intact, the other memorialized by a column of light. It's still one of the ballsiest moves in comics: released just three years after 9/11, Ex Machina probed a wound that was still raw. This wasn't a firefighters' or victims' fund comic with splash pages of Doctor Doom crying over a pile of rubble; this was an iconic image revised, and the most traumatic event in recent American memory used as fodder for a superhero comic.

Of course, you can be ballsy when you're that good. Throughout its 50 issues (and four specials), Ex Machina explored the realities of politics, the public's relationship with its heroes, the ongoing fear of terror, the responsibility of journalism, the corrupting influence of power, and the upside-down world of New York after the fall, using the superhero comic as a delivery system to express the vital concerns of the age.

It was in such a perfect, succinct testimony on the state of politics and power in the country post-9/11 that Vaughan had no critical need to come near the territory again.

But the effects of 9/11 are still being felt today, rolling across the years like seismic waves, and Ex Machina wouldn't be the last time Vaughan dived into them. In fact, it wasn't even the first.

Vaughan contributed a story to 9-11 Vol. 2, DC's half of the comics industry's contribution to relief funds, but even before that, the terror attacks had a direct impact on his work.

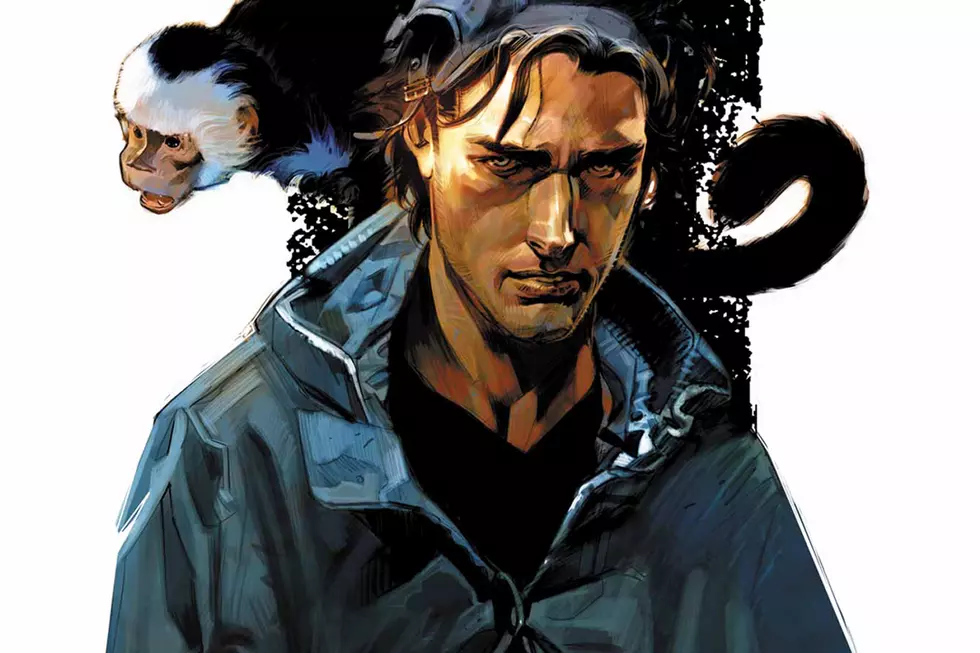

Y: The Last Man with Pia Guerra, which launched two years before Ex Machina, was actually still in the development stages on September 11th, 2001. In fact, artist Guerra was supposed to start working on the first issue that very morning. Obviously, production was pushed back, and even though Vaughan was comfortable enough to engage the event head-on in Ex Machina, he elected to remove a reference to the Taliban from the first issue of Y: The Last Man.

In the original script, Agent 355, the Culper Ring spy who protects Yorick, was introduced on a special mission in Taliban-occupied Afghanistan. Vaughan cut the Taliban and altered the setting to Jordan, a no-brainer when you consider the higher plane of sensitivity in the days following the attack. But Vaughan and Vertigo might easily have felt some rush of prophecy - like so many others did -- and left those elements in, to reap whatever special significance conspiracy fans might have chosen to bestow upon it. (There are people who think The Matrix predicted 9/11.)

Unlike most post-apocalyptic fiction released around 2000, Y: The Last Man wasn't an expression of millennial anxiety; it was constructed to use the form of a millennial fear to explore the similarities and differences between the genders. But with one of those fears scratched into reality on Vaughan's immediate horizon, his perspective understandably changed.

The biggest impact that 9/11 had on the book, oddly enough, were the vagina jokes. (There were a few, right? Or am I just having a creepily specific false memory?) Apparently, Y: The Last Man was originally going to be one long, drawn-out bummer, because according to Vaughan, "on 9/12, there was a lot of dark humor, and I got to incorporate that into Yorick, that lightheartedness-as-coping-mechanism. And that kept Y from being a dour book."

Having a more thorough understanding of the human response to disaster, Vaughan was able to mold incredibly real characters that spoke directly to a culture-wide awareness that hadn't previously existed. Yes, the book is re-examination of gender relations and identity issues in a new social context (which, according to an essay in Graphic Novels And Comics In The Classroom, some interpreted as directly-related to racial identity post-9/11), but I don't think that's necessarily the reason why anybody really cares about it.

Y is beloved because of its characters, and the ways in which we see them cope and react in a world turned upside-down; a struggle that was suddenly much more familiar to us.

In the years following September 11th 2001, Vaughan continued to explore the long-term effects in his work. Three years deep into the Iraq War (and three years after George Bush declared it over in his "Mission Accomplished" speech), Vaughan penned Pride Of Baghdad, inspired by true events. In April 2003, four starving lions who had escaped the Baghdad zoo were shot by American soldiers. Pride of Baghdad, illustrated by Niko Henrichon, offers an appeal to basic human sympathy, and of course the most effective way to do that -- especially in comics -- is through the abuse of cartoon animals. Americans care way more about cartoon animals than they do actual people.

In Saga, with Fiona Staples, Vaughan makes less direct reference to post-9/11 conflicts, but the connections are there. In numerous interviews, including one with ComicsAlliance, Vaughan has mentioned that the relationship between Landfall and the Robot Kingdom mirrors that of the United States and Saudi Arabia, an uneasy but mutually-beneficial relationship built on commerce.

Even if that connection weren't made apparent, the relationship between Landfall and Wreath would still be an evident metaphor for the struggle between America and predominantly Muslim countries (pick one). Landfall is technologically superior, fully modernized, and entertainment-obsessed; the people Wreath are a faith-based, family-oriented culture who are referred to as terrorists. So when Alana falls in love with Marko in the prison camp, it's the metaphorical equivalent of Lynndie England falling for one of the guys whose dicks she was so charmingly pointing at. (Yeah, I'm not linking to that picture. You'll have to do the work on that one.)

I've read more than a few opinions that interpreted Saga as a "sci-fi Romeo & Juliet," but that's a lazily reductive summary of a story that addresses a very real problem that scores of people struggle with every day. In Saga, like in Y and Ex Machina, the genre is just the delivery system to explore significant real-world issues. Namely, how the hell do you raise a kid in a world that seems constantly at war?

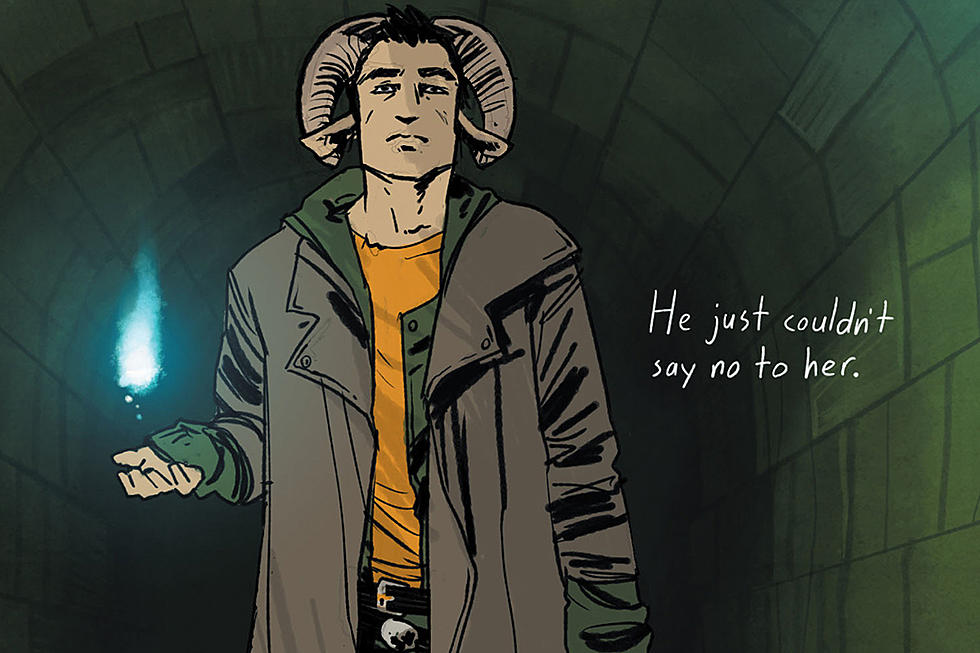

There are also parallels with post-9/11 realities in The Private Eye with Marcos Martin. Though the book is primarily concerned with Internet privacy as it relates to our personal lives, there's an undercurrent of criticism in how it relates to nationalism as well. In the context of the future that Private Eye portrays, "The Flood" is their 9/11; a traumatic event that triggers a definable change in popular American identity. As a result of "The Flood," personal privacy is the chief concern of the nation, and within the country's borders, the Internet is entirely disabled.

That seems very much like an inversion of what happened after September 11th, when the chief concern of the nation became security, and privacy took a back seat, whether we wanted it to or not. The Patriot Act, Sprint wiretaps, PRISM, and every other perversion of our rights, claims 9/11 as its justification, and our collective response has amounted to little more than begrudging acceptance.

The citizenry of Private Eye have completely shut down the internet inside American borders, literally walling themselves off from the rest of the world (and after 9/11, did you happen to hear anyone discussing that very idea completely without irony, or was I the only one?) and surrendering the most powerful tool to affect social change in human history. It's a culture that's traded ignorance for privacy, much as we brokered privacy for security. Implicit in the villain De Guerre's criticism of their isolation is a commentary on what American citizens are willing to allow.

Maybe.

I have no special insight on Vaughan's life or how he expresses himself, and the point of this article is emphatically not: "Hey guys, Brian K. Vaughan was in New York on 9/11 and he can't get over it, isn't it great!?" (But please feel free to use that as a pull quote, Image.) I despise the certainty with which critics unlock the secrets and expose the hidden meaning of any creative endeavor without at least once acknowledging that we're all just guessing. Every critic/reviewer/annotator's byline should include a pic of them exaggeratedly shrugging. I gleefully acknowledge it: maybe my awareness of Vaughan's presence in New York on 9/11 had me chasing a faint thread through much of his work, interpreting broad statements to be specific ones; maybe I just had a decent idea for an article and saw what I needed to see in order to write it; just because I believe that our relationship with the Middle East, racial politics, and the state of American privacy have all been affected by 9/11 doesn't mean that Vaughan or anybody else has to.

But Vaughan has frequently said that his comics come from questions that he feels the need to answer, and more often than not those seem to be questions germane to larger conversations of our national identity. He's a writer for his times, and the last thirteen years have been some very confusing ones. When it comes to the realities of post-9/11 America, Brian K. Vaughan isn't going to have the answers, and he might not even be looking for them, but he has articulated numerous concerns about our collective state nonetheless. I have no idea if it's intentional or not; I just find it interesting that he's asking all the right questions.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Comics’ Sexiest Female Characters (From A Queer Perspective) [Love & Sex Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/02/hg_featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)