Celebrating The Mad Vision Of William M. Gaines

Horror. Crime. Science Fiction. War. Suspense. Oddball humor. Incisive writing. Eye-popping art. These are the elements that made EC Comics irresistible to readers of the 1950s. Their titles were produced by some of the finest creators the comic industry has ever seen, a who's who of boundary-bursting, wildly innovative talents: Wally Wood, Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis, Will Elder, Johnny Craig, Frank Frazetta, Al Feldstein, Al Williamson, Joe Orlando, John Severin, Graham Ingels, Bernard Krigstein, and many others.

And when the bubble burst, and EC's line of comics fell before a squalling mob of censors, Senators, sinister psychiatrists and simple-minded puritans, one series managed to escape, transform itself into a full-size black-and-white magazine, and go on to turn American culture upside-down with its cleverly absurd approach to humor.

Through it all, there was one constant figure lurking behind the scenes: publisher, co-editor, troubleshooter, troublemaker, and visionary William M. Gaines.

William Maxwell "Bill" Gaines was born in New York City on March 1st, 1922. His father, Max Gaines, was one of the pioneers of the American comic book, releasing one of the first color comic-strip reprint pamphlets in 1933, and founding and publishing All American Publications in 1938 (which would eventually merge with National Publications and become what we know as DC Comics).

Young Bill was by most accounts a sensitive and intelligent child, and had no interest in following in his father's footsteps. He had a keen interest in science, and after high school, attended NYU and planned to make a career teaching chemistry. Meanwhile, Max sold his interest in All American, and founded a new company, Educational Comics, which specialized in "Picture Stories" on topics like American history, great scientists, and the Bible.

However, in 1947, the elder Gaines was killed in a speedboat accident, and Bill left school to take over the family business. What ensued is the stuff of legend. Over the next few years, Bill converted the floundering company from Educational Comics to Entertaining Comics, experimenting with different genres (Western, romance, action, crime, funny animals), and gathering together a simpatico group of editors and creators.

At the beginning of 1950, he and editor Al Feldstein introduced a pair of of creepy narrator characters for some stories tucked into the back of their crime comics, and two issues later, the Crypt-Keeper and Vault Keeper took over top billing. Crime Patrol and War Against Crime were converted into The Crypt Of Terror and The Vault Of Horror, and Bill Gaines began to realize that he didn't just have to chase trends --- he could find success by producing comics that he actually cared about.

The "new" EC Comics was now properly off to the races, and Feldstein, Gaines, and new editor Harvey Kurtzman took their stable of creative talent and expanded in every direction. Tales From The Crypt. The The Haunt Of Fear. Weird Science. Weird Fantasy. Shock SuspenStories. Crime SuspenStories. Two-Fisted Tales. Frontline Combat. And a couple of humor books called Panic and Mad. These new titles were a world away from the company's previous output. They were aimed at older audiences, and pushed the envelope in terms of content and presentation.

Sales skyrocketed. The creators reveled in their newfound freedom. Gaines realized that he was creating something successful. And EC titles began to outsell their competitors.

But dark clouds loomed. A noted New York psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham, had been publishing anti-comics articles to great acclaim, writing for magazines such as Reader's Digest and Ladies' Home Journal, and his 1954 publication of Seduction Of The Innocent, a full-length book on the connection between comic books and social ills, made him the flashpoint for a nation already teetering on the edge of Joe McCarthy-inspired paranoia.

Anti-comic actions had previously been scattered, isolated events. Now, churches, scouting groups, schools, and charitable organizations around the country were hosting comic bonfires. And as EC was constantly pushing the envelope, Bill Gaines was caught right in the crosshairs of public opinion.

In the spring of 1954, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held a series of hearings on the effects of comic books, and Gaines decided that he needed to testify and stand up for his livelihood.

It didn't go well. Gaines was suffering from a cold on the day of his testimony, and was under the influence of various medications. He showed up, read a prepared statement, fumbled when pressed for clarification, and stumbled his way through answering some very pointed questions from the presiding senators.

By the fall of 1954, a coalition of publishers formed a new trade group, the Comics Magazine Association of America. After some short deliberation, they instituted a new series of strict guidelines for their product, effectively self-censoring in hopes that the government would leave them alone. Rules included bans on words like "terror" and "horror" in titles, restrictions on visual depictions, and a note that all authority figures must be portrayed with respect --- in short, rules that may as well have been written specifically to address EC's house style. And while the Comics Code regulations came with no legal authority, the fact that the publishers in question also controlled newsstand distribution meant that Gaines had little choice but to comply.

EC floundered along for a short time, launching a "New Direction" line of less-controversial comics, including Valor, a book about heroism through history; Extra, a book about intrepid journalists; M.D., a book about doctors; Aces High, a book about aviation and air combat; and Psychoanalysis, a book about…well, yeah.

But within a few months, all those titles had folded. And Gaines had made one last-ditch effort. He was focusing all his attention on the one that survived, a humor series that he converted into a proper black-and-white magazine in an attempt to circumvent the Comics Code and provide a new challenge for editor Kurtzman. And while that may have been a gamble brought about by necessity and desperation, it also proved to be the move that solidified Bill Gaines' place in history.

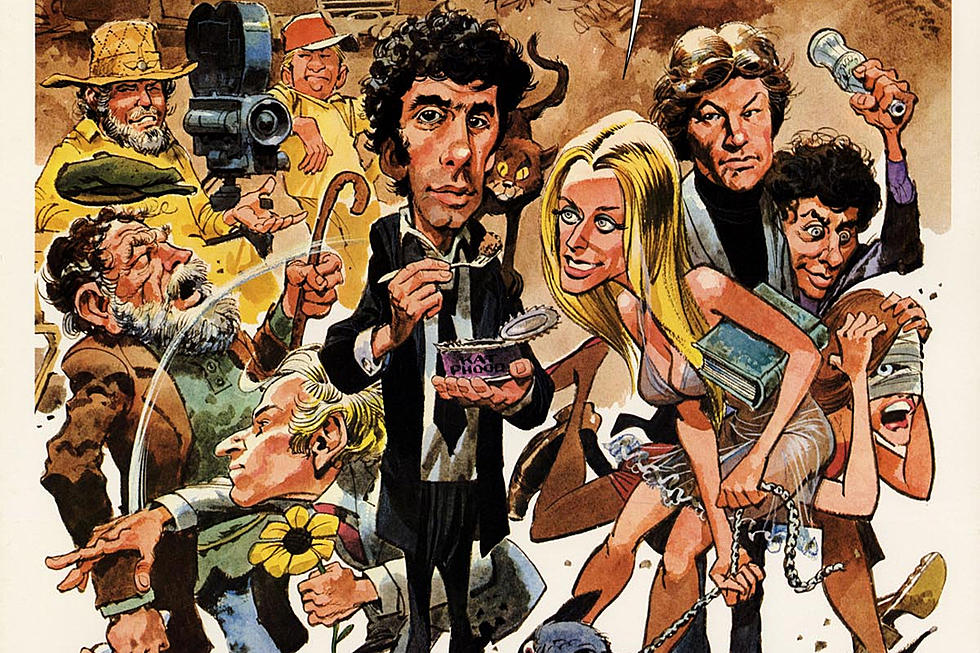

The new Mad Magazine was, to put it mildly, a sensation. And though Kurtzman left for greener pastures shortly after the revamp, Gaines and Feldstein steered the ship wisely, lending Mad an air of irreverence that sent shock waves through popular culture, and has influenced nearly every comedian and humorist in its wake. Most importantly, Mad's creators realized that by poking fun at the powerful, they themselves were worthy of skewering, creating an air of wild but never-vindictive chaos that permeated each and every page.

Over the next four decades, Gaines presided over Mad's "Usual Gang Of Idiots", a loose consortium of contributors that mixed longtime EC creators like Jack Davis and Will Elder with newer figures like Al Jaffee, Dave Berg, Mort Drucker, Antonio Prohias, Duck Edwing, Frank Jacobs, Tom Koch, George Woodbridge, Dick DeBartolo, Don Martin, and oodles of others. The magazine sold like hotcakes, spun off a pair of successful record albums, a series of paperback books, an off-broadway show, a board game, and a never-aired TV special.

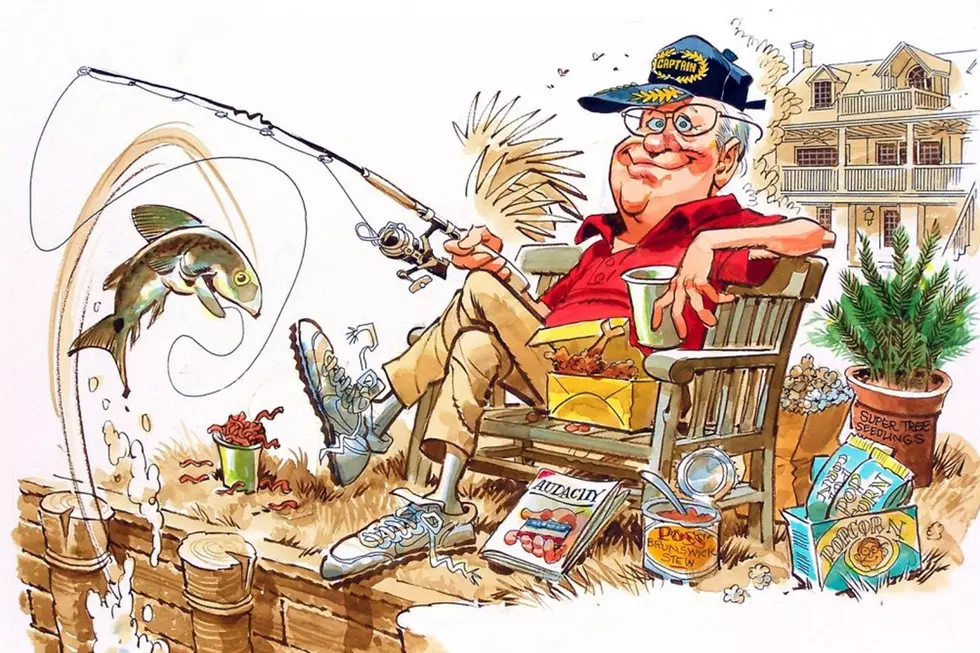

Gaines also developed a reputation as a generous-yet-particular boss, one whose individual vision for Mad was clearly-defined, but not always comprehensible. He would penny-pinch whenever possible, yet spring for outlandish employee dinners and elaborate staff vacations. He spent extra for lower-grade paper stock, to ensure the magazine maintained its identity. He maintained an entirely freelance staff, but earned a reputation for prompt payment (usually cutting checks immediately upon delivery of an assignment).

And though he passed away in 1992, his vision is ever-present. The Comics Code finally ceased to operate in 2011, after years of rollback. Horror, suspense, comedy, science fiction, and other genres have reestablished themselves as important pillars of the comic industry, after generations of superhero domination. Mad has spawned two separate successful TV shows, and the magazine continues to thrive, providing a forum for the funniest and sharpest talent the industry has to offer.

So today, we celebrate Bill Gaines' birthday, his innovations, and his legacy. We note his impact on comics, and on all of popular culture. And we suspect that wherever he is right now, he's probably laughing at us for spending so much time talking about him.

More From ComicsAlliance