Chip Kidd and Dave Taylor Build an Ideal Batman Story in ‘Death By Design’

This summer audiences are seeing two very different takes on the Batman character and his story that rather radically depart from the one that appears in DC Comics' regular publishing line. The company released Batman: Earth One, an original graphic novel by Geoff Johns and Gary Frank, which tells an alternate origin story more grounded in reality and intended to appeal to a more casual bookstore audience, as opposed to weekly comic shop customers. And Warner Bros. released The Dark Knight Rises, which wraps up director Christopher Nolan's incredibly popular film trilogy about a masked vigilante in a world free of superheroes and their narrative conventions.

A third alternate and similarly accessible take on the character was recently released, however, that hasn't received anywhere near as much attention as the other two -- but it deserves to. Chip Kidd and Dave Talyor's graphic novel Batman: Death By Design, which sets the Dark Knight in a world reminiscent of Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and where aesthetics and adventure combine in uncommonly explicit fashion.

Kidd is an accomplished book designer who's probably best known to comics readers for his work for DC Comics, including the often imitated logos for All-Star Superman and All-Star Batman and Robin, The Boy Wonder, and art books Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to Their Limit (with Art Spiegelman) and Mythology (with Alex Ross), as well as some mildly controversial projects like Bat-Manga and Shazam!: The Golden Age of the World's Mightiest Mortal.

Kidd's also a writer, having produced a pair of novels -- The Cheese Monkeys and The Learners -- in addition to his non-fiction writing, and those are two skill sets that synthesize quite perfectly in his Death by Design.

His partner on this particular work, Kidd's first full-length graphic novel, is artist Dave Taylor, who previously drew Batman in the 1990s, mainly in the monthly series Shadow of The Bat. The method and style Taylor adapts here, however, make the visuals appear to be the work of an entirely different artist.

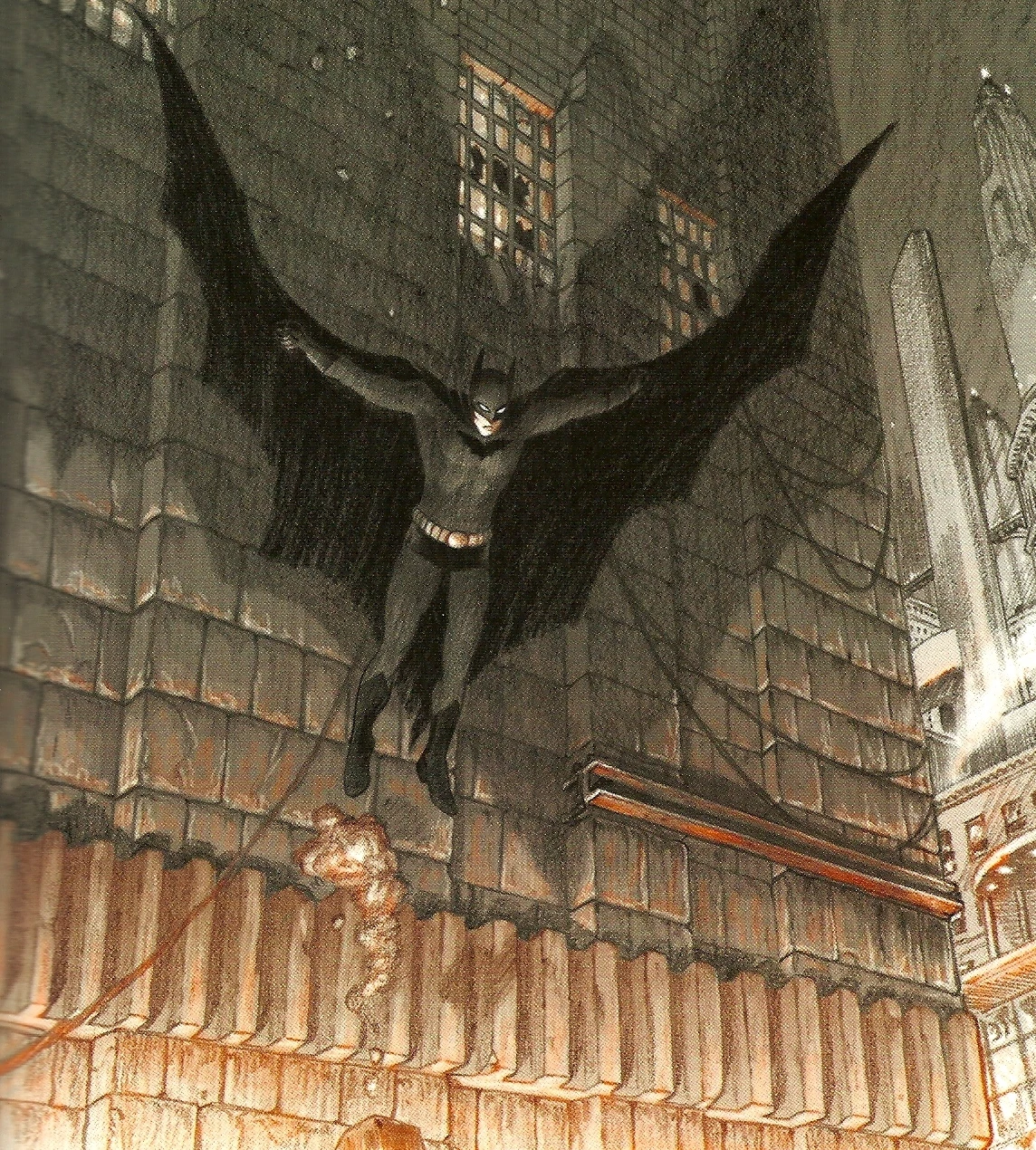

Their Batman, like the character in Earth One and Nolan's movies, is his own Batman, with his own look and his own world. His costume is heavily informed by the one his first artists drew in the Batman's first appearances, right down to the cut of his trunks, the shape of his ears and edges of his cowl; they even include a panel where his cape flares up to simulate the erect bat-wings of the very first Batman comics images of the 1930s.

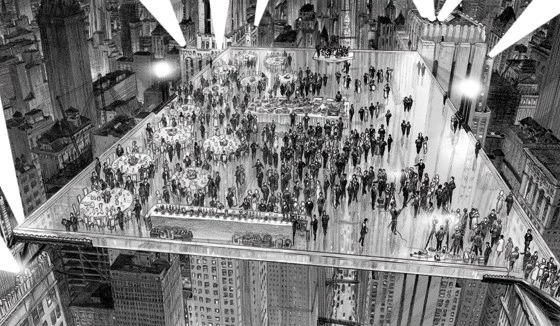

As is appropriate given the title, this is a Batman narrative almost completely defined by its design and aesthetic sensibilities, to the degree that I'm having trouble thinking of a Batman anything as thoroughly and completely visually detailed as this since the Tim Burton Batman films. Perhaps Batman: The Animated series, with which the book shares an ambiguity regarding its setting in history. As in the animated series, everything looks as if it's taking place in comics' pre-war Golden Age, but modern technologies like computers and futuristic concepts like a hologram projector and a hand-held personal force field generator exist -- they just look like they were designed by Madison Avenue ad men circa 1942.

Familiar faces appear in Death by Design, including Alfred and The Joker, plus a single panel of The Penguin and references to Harvey Dent and Commissioner Gordon. The Joker is a rather unique take, with blackish gums, black-red lips, luminescent pale blue hair, and purple neckwear, but otherwise completely drained of color like so much of the book. The other characters look more or less standard, although every character, new and old, is dressed in 1940s Hollywood costumes.

The story is a fairly standard murder mystery type, of the sort that might have been eight-pages in a Golden Age comic but fleshed-out characters and filigreed fantasy-history make Death by Design novelistic in length.The crumbling Wayne Central Station, commissioned by the late Thomas Wayne, Batman's father, is about to be demolished in order to make way for a new Wayne Central Station. The new building is to feature an ultra-modernist architectural design. Architecture expert Cyndia Syl, who wrote her thesis on the original Wayne Central, wants to save the building because she believes it's an architectural treasure, one created by an eccentric Gotham architect who has since gone into hiding.

Meanwhile, someone seems to be trying to kill Bruce Wayne and a union boss responsible for the shoddiness of the original station. A mysterious, banshee-like figure who looks like a Republic serial mystery man and calling himself "Exacto" appears to warn of impending doom. An architecture critic investigates the strange goings-on. And The Joker is on the loose, doing Joker things.

Kidd's plot is straightforward but engaging in its old-fashionedness, as he puts Bruce Wayne/Batman in the interesting position of being the bad guy and the good guy simultaneously, depending on the point-of-view of the character he's dealing with. While there are attempts at murder, there's not a whole lot of black-and-white good and evil in Death by Design (with the exception of The Joker); the characters basically see things in different ways, and Batman's journey isn't merely beating up the bad guys, but coming around to seeing things one way after having started out seeing them a different way.

What really elevates the book beyond a pretty good, much-better-than-average Batman story, however, is Taylor's artwork, and the degree to which he and Kidd have built the book's world as a cohesive whole that all fits together and works the way a world actually might, all while looking like its own place and distinctly different from our own. Taylor said the entire book was done in pencils; "penciled" with blue pencil and "inked" with graphite, and with no lines erased. Shading and bits of coloring were later done with computer. As such, the grit of the pencil lines and the grade of the paper form the raw materials of everything you see, from the detailed architectural drawings of buildings and the fabric of Batman's tunic.

Death by Design is not quite black and white, although it looks awfully close, with most scenes having only highlights of a third color. A daytime business meeting, for example, will be set in black and white save for some golden sunlight shining through a window and reflecting off select objects in the room; or the aforementioned Joker's splashes of color, singling him out from a crowd. The subtle, restrained coloring allows the pencil lines to remain visible and to define the artwork. Unlike most comics art produced with computer-coloring over pencils, the colors here never absorb the line artwork itself.

Additionally, there are so many more darks in the scenes in which Batman appears, with his black cape and cowl, that there's a sharp, visual division between Batman scenes and Bruce Wayne scenes, and between nighttime action scenes and daytime plot-advancement scenes.

Compared to other new Batman stories available this summer, Death By Design certainly seems to be the least flashy and the least ambitious in terms of reinventing the wheel that is Batman, but it also seems to be the most potent in terms of getting at the most basic appeal of the character and exploring it: the striking bat-costume wrapped on a man running and jumping through a classic urban setting. And, unlike the films and video games that now make so much money as to make the comics themselves seem incidental (if not downright irrelevant), the book does so with the character as he was originally conceived -- as a drawing on a piece of paper

Batman: Death by Design is on sale now in finer comics shops and bookstores.

More From ComicsAlliance