ComicsAlliance’s Best Comics of 2010: #1 — Duncan the Wonder Dog

The relationship between people and animals is often complicated, and has always been complicated since the first moment of domestication, when we made an animal more to us than just a living vessel of protein. What could we do? It followed us home. Given enough time, animals have a habit of making their way into our affections, despite the fact that we frequently slaughter them for food, sport, or resources.

It gets even more complicated when they can talk.

Duncan the Wonder Dog, the best graphic novel of 2010, explores a world that is in many ways like our own, except that animals can understand and speak human language, a change that affects our society through: a) more complex relationships between owners and pets, b) an increasingly violent animal rights movement lead by animals themselves, c) exponentially more upsetting slaughterhouses, or d) all of the above.

The answer is d). It is also a lot of other things.

A few more facts about Duncan the Wonder Dog: It the first published work of Adam Hines, a virtual unknown who has had no formal art training whatsoever. It is 400 pages long, took him seven years to complete, and is the first book in a nine volume series that he plans to spend the rest of his life creating.

Ask an editor at most comic book publishers how appealing that pitch sounds, and you'll probably hear that it reads like a textbook example of the hubris all too common in amateurs whose reach exceeds their grasp. It's the comic book equivalent of sitting down to write your first piece of prose and declaring that you're planning to compose the Great American Novel.

Except that Adam Hines just did it.

Duncan the Wonder Dog is a virtuoso debut, a display of talent so sudden and fully formed that it requires a strange sort of wunderkind brilliance, like a child speaking for the first time in complete sentences. Hines has the careful, patient hand of a master, packing each page with pitch-perfect dialogue and characterization, expert world-building, and formal experimentation, each panel as carefully placed as a mosaic tile. Its intentions are so vast and ambitious that it seems destined to fail, but instead it succeeds wildly.

Many of the characters we meet throughout the book never appear more than once, but the recurring cast includes Voltaire, the fiercely intelligent gibbon who demands – and receives – a seat at the tables of power in business and politics; Vollman, the arrogant, glad-handling bureaucrat who is all too ready to compromise animal rights for political points; Pompeii, the thoroughly psychopathic monkey terrorist who detonates a rather large explosive in a university library in California, and Jack, the embittered detective who reluctantly takes charge of the bombing investigation.

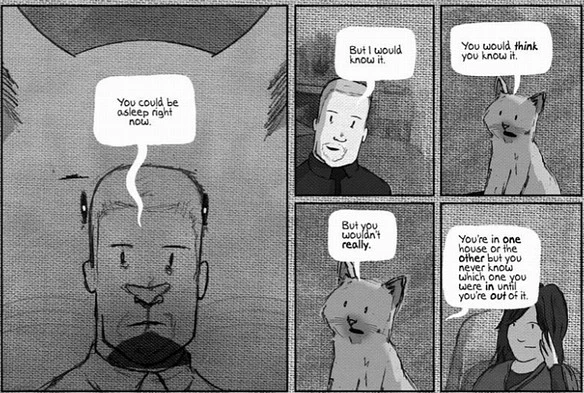

After the bombing, a man in a bar asks a monkey what he thinks of the whole thing. The monkey replies, "I think humans have only two points of entry to veracity," the monkey replies. "When presented with any number of options, half of you would choose to believe one because one of them could be true, and the other half would abstain from making any decision at all to avoid fault. One or the other. And these two points – believe truth and avoid fault – form a ray that cuts through all of human development. I don't think many animals could imagine living like that. You say to a human that the sun is either up or down, and that human will nod his head in agreement. Two points of entry, and you're done."

That is the human story, but that is not the only story.

Duncan the Wonder Dog is not so easily divided, by design. Its story is not a straight line, but rather something more circular, an elliptical, shifting narrative that moves between the human world and the animal world, but is most concerned with the places where they overlap and defy easy categorization. The very idea that life can be interpreted and codified through simplistic dichotomies is portrayed as a very human point of view, created by people who believe that truth is a singular thing and that it is not only knowable, but that the entire world can be divided along its axis into correct and false, right and wrong.

There are many points of entry in Duncan the Wonder Dog: fables, allegories, diaries, stories within stories. There is a sense of collage that permeates the pages, in the most literal way: ticket stubs, library cards, clipped newspaper columns, maps, diagrams, measuring tapes, entire pages of textures, and most frequently, the wordless landscapes that appear between vignettes, or maybe as vignettes. And then there the flexible reed of the art itself, which sways from sweetly cartoony monkeys to photorealistic tigers within the same panel.

While others could argue to the contrary, and have, the result for the patient reader is cohesive. It accumulates the story in the form of ephemera and lets it sort slowly into patterns, like a planet that learns the shape of its world by orbiting it.

The book begins not with a bomb, but rather another very definingly human display of violence: a boxing match, and one that actually happened, between Rocky Marciano and Ezzard Charles.

As far as metaphors go, a boxing ring is not a bad one for explaining how our world is different from the animal world, namely how it is both systematic and vaguely hypocritical in its attitude towards violence. The point of boxing is for two people to beat the hell out of another for the entertainment of others, but because we are civilized, we create rules like ropes to govern the violence.

Human rules about violence – like our rules about war – can be comforting, in a way, because they make that it make it feel like something organized and systematic rather than random or cruel. They make it part of something comprehensible, maybe even something that seems fair, and often, we congratulate ourselves for it -- how civilized we are in in the midst of our uncivilized acts.

You can hear that pride in the voice of the radio announcer after the boxing match when he lauds two fighters, his voice floating over the radio to a man sitting in a living room:

"Not once all the way through there an unpleasant demonstration... The men, both Rock and Charles, were sportsmen-like with each other -- as sportsman-like as I have ever seen -- I don't remember Ruby ever having to separate the two fighters -- and all-in-all I think it was one of the most brutal, yet professional heavy weight fights we have had in the annals of the pugilistic games."

"Brutal, yet professional." What better way to describe us, as a species?

There are a couple of difficulties in addressing the issues raised by Duncan, and appropriately, they all reflect our total self-absorption as a species. The conceit of the book is essentially a thought experiment: If animals had the capacity for human language, how differently would we see them? How much more difficult would it be to treat them like walking cold cuts? While Hines does an admirable job of trying to make the culture and the interactions of the animals distinct, ultimately what makes them seemingly worthy of better treatment is that he literally humanizes them; he transforms them into beings that are more similar to us.

The second problem is one of vocabulary, because our lexicon is so suffused with the idea of human supremacy that it's nearly impossible to talk about the idea of sentient beings or the concepts of dignity and respect for other living creatures without saying the word "human." Our "humanity" is what makes us empathetic to others, while debasing others is "dehumanizing." If the way we treat an animal is "inhumane," doesn't that just mean we aren't treating it like it's human? Isn't that what animals are?

From a historical perspective, the story of how people treat animals in the world of Duncan is a familiar one; it's the story of how we have treated countless groups of people that that we deemed insufficiently similar to ourselves. While the book isn't specifically focused on drawing comparisons to slavery, civil rights, and genocide, the anthropomorphism of the story makes it pretty much impossible to ignore.

We see it in echoed the small indignities and slurs that Voltaire suffers, despite his relatively exalted position in human society, and the everyday reminders of powerlessness in the lives less fortunate animals, like the fisherman tells the bird it works with that it has to deliver all the fish it catches today without eating any: "I'm one of the only fishermen who will work you without a snare, but I can put one on if I need to." There is a brief but powerful panel where we see the Venn diagram where the human world and the animal world lie over each other, like transparencies: the bird curling into itself, while a shadow version lunges forward into the light, wings extended.

There are funny moments too, in the transition to a world of talking animals, like the scene where filmmaker making a nature special follows a group of primates along a coast trying to get footage of their mating season, and ends up getting an earful from one of the males who has had just about enough of the stalking. "All the women are pregnant, you missed all the action, you giant perv, just so move on up the coast," he shouts.

The contrast takes on a terrifying tenor in a scene at a cattle stockyard that feels ripped straight out of a horror movie, as two men alternately abuse and cajole a cow in a flatbed truck, trying to convince it to walk towards what they deny but we nonetheless assume is a slaughterhouse.

The workers finally pull the cow off the flatbed with brute force, breaking its leg. When the men they report the injury to the foreman, they grumble at the inconvenience of having to phone in the incident, and process the cow through the proper channels. This is the difference between us and them: We have a system, and it has rules. We aren't animals, after all.

When the appropriate official arrives at the stockyard to deal with the cow and its broken leg, he does so by shooting it in the head. "I coulda done that," says the stockyard worker. "No, you couldn't," says the official.

"Slaves be submissive to your masters," quotes the terrorist leader Pompeii from the Bible to a hostage shortly after killing his wife and child but shortly before hitting him with a tire iron. "Inside joke, you don't get it, you're not on the inside."

Pompeii is a leading member of ORAPOST, the radical group behind the university bombing, and the living personification – for lack of a better word – of the madness that happens when you force nature into boxes, the frenzied, furious heart of a caged animal raging into the tiny body of a female Barbary macaque holding a machine gun. She is terrifying.

Pompeii hates humans with an incandescent, jagged hatred, but inside that rage is a secret, and it is her most terrible one: She is not so different anymore. By engaging the human world, even with violence, she has already been changed by it; she is already more like humans that she would ever want to recognize.

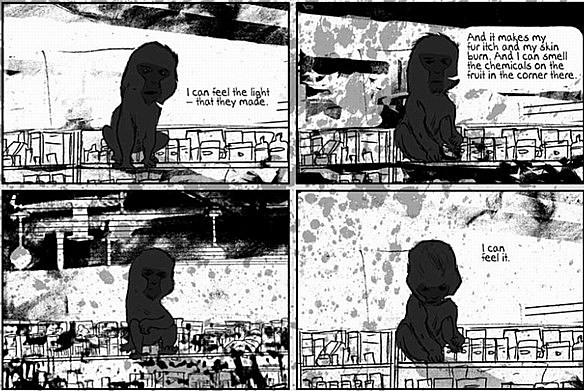

After murdering a family, Pompeii sits in their suburban home and read the diary of the mother, which details their moving – if still unequal – relationship with their dog, Bundle. When Pompeii finishes, she burns the diary. It is not a point of entry she wants to hear. She, too, has started to see the world broken like a tile into only two points of view, and it is slowly driving her insane, like the endless buzz of a fluorescent light. "This isn't a prison," she says to herself towards the end of the book. "We can leave any time we want." But there she is anyway, a tiny, anthropomorphized monkey screaming in the middle of a convenience store she has successfully locked herself inside.

There is an unspoken question in most speculative fiction, and in Duncan, it is "how horrifying would it be if we lived in a world like this?" The answer, which is worse, and also a question, is "what if we already do?"

Another review of Duncan criticized it for not being angry enough about animal rights, which was useful to me because it helped crystallize exactly what is so successful about the book: It is not a polemic; it is an exercise in empathy. If it is about anything, it is about perspective, about how many perspectives there are, and how all of them overlap and interact with each other like vibrations from a tuning fork. It is a story that is like every story, and every story is the definition of empathy: Imagining for a while that you are someone else. The world of Duncan is only as upsetting as you are empathetic, but then that is true of our world as well, and of any injustice that is not your own.

As a species, humans are dazzlingly creative beings, and as such we do not simply live in the world; we create our own through sheer force of will, in ways both real and imagined. One of the things that we say separates us from the animals is our power of imagination, our ability to see things not only as they are, but as they could be. And also, the ability to see things not only as they are, but as we wish to see them.

As such, the best way to reach into our hearts is to show us a mirror, and ask us to love ourselves in the form of something else.

The problem with the story of people is that it is often a lonely and frustrating story, at least from a broader perspective. If we believe we are the world, then it can never be any bigger than us. We make ourselves stars, rather than constellations, meaningless and singularly bright, sunk to the bottom of the the dark sea of absolutely everything else.

It is a strange, existential loneliness, and one that we choose, the way Jack chooses emotional detachment as a way of coping with the horrific bombings he has repeatedly investigated. He sits at a bar in one scene and catalogs a series of random memories: A beautiful woman in a sweater dress. Cutting his hand on a broken light bulb. The time a crying baby sounded like an injured cat. The moments are monoliths, as disconnected as he is, with no larger or more cohesive story: "He tried to find a through line for all of this, a way to connect these disparate moments, but he couldn't."

Very possibly, some people will feel this way about Duncan the Wonder Dog. They should try harder. We should all try harder.

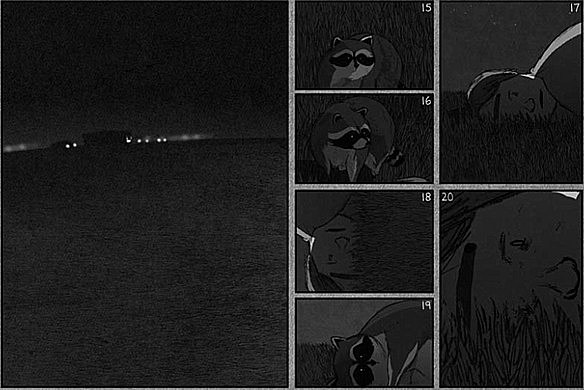

Hines slides us behind the eyes of one scene after another: a man begging for his life in a field, a flock of birds hung with empty speech bubbles, a raccoon who finds a human body on the ground and tilts his head to look in its eyes. Hines pulls in on the smallest moments, a ladybug lighting on a man's hand and then disappearing, and the world expands inside them; he pulls back to a black page with a single tiny sun, smaller than a dime, circled by an even smaller planet. We see the world, and then we see perspective. Everything scales both up and down, especially stories.

There is suffering, but there is also something bigger than that, a context that is larger and longer, and it connects us. It is a story we do not like to tell because we do not like stories that are bigger than us, or the statues we make to ourselves. We want to believe that the entire world is circumscribed in our skin.

"That's the difference between you and us," hisses Pompeii at one point. "It's the process that matters, not your whining. And for all your stinking fears of permanence all that will be left is your meaningless struggle carved in rock."

Near the end of the book, one chimpanzee tells another chimpazee a story – the last story, and the biggest one:

"The sun will burn out and this planet will turn into a frozen ball of ice. Everything and everyone will die, and more than that, there won't be any evidence that anyone was here at all. There are some that say that because of this certainty, nothing anyone does can ever really matter. They say nothing can matter if everything will end."

But what have we learned? That is only one point of entry. That there are more stories in each day, let alone all of them, than sun up or sun down.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Sold-Out ‘Duncan the Wonder Dog’ Now Available for True Digital Download [UPDATED]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2011/01/duncan-ipad.jpg?w=980&q=75)