Cash Rules Everything Around Eddie Campbell in ‘The Lovely, Horrible Stuff’

Money. Money, money, money, buzzing around in the news, whirling past your eyes and into your gas tank at light speed while the pump excitedly displays your negative winnings like a slot machine from the Bizarro Universe. Unless you're very rich, money has to be on your mind more than usual. It's been on Eddie Campbell's mind too. And being the fertile, inquisitive and well-informed mind that it is, it eventually just had to result in a new book. The Lovely, Horrible Stuff coming from Top Shelf Productions this May dives Scrooge McDuck-like into the topic of cash and comes up with pockets full.Across a long career of portraying his own life in autobiographical (or semi-autobiographical) comics, Eddie Campbell has tangled with the subject of money before from time to time. The earliest Alec strips, were all drunken escapades and relationship drama, where trips to Europe seemed to be paid for with couch money. But he "Alec" went on to have a wife and family, his sobriquet disappeared, and "Eddie" suddenly had to deal with financial reality. Over the last ten years, money has become a more frequent topic for the Scotsman, and the freewheeling Kerouac chaos of early Alec was replaced with the minutiae of self-employment and family life. To an even more engrossing affect.

With typical anecdotal ease, Campbell chronicles the rises and pitfalls of living off of intellectual property, ruminates on the very concept of compensation, and explores the impact money has on family relationships. As usual, it's sly, funny, and meandering without ever losing course. Campbell is perhaps the most natural storyteller in comics, and makes manic little leaps through tales, always maintaining the reader's rapt, giggly attention.

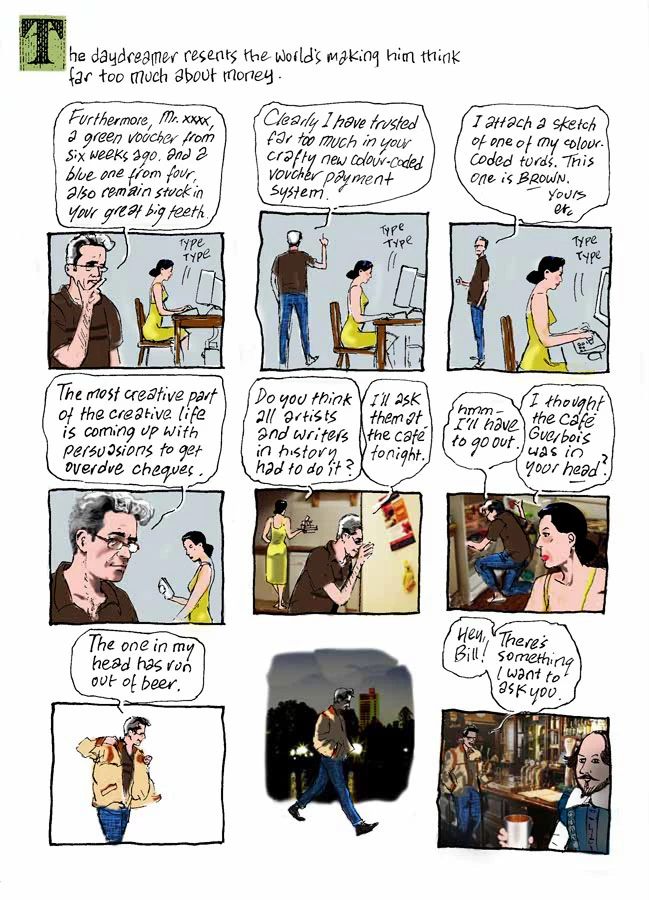

In his comics, Campbell has tended to wear his cheapness proudly, but in The Lovely, Horrible Stuff, he goes into greater detail. Campbell's philosophy regarding money is a simple one: money equals time. Time for the artist to delve into his own head for months at a time and return with something new, which would earn the artist more money, giving him more time, and so on. Intellectual property is something Campbell keeps coming back to, and the financially wobbly tightrope it can be, filled with dizzying peaks and stomach-churning lows.

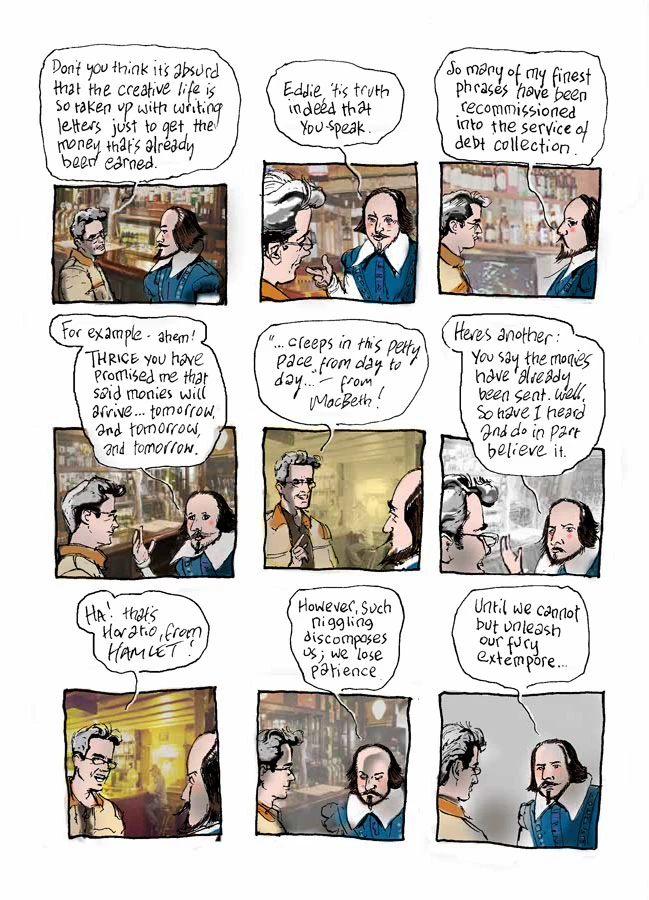

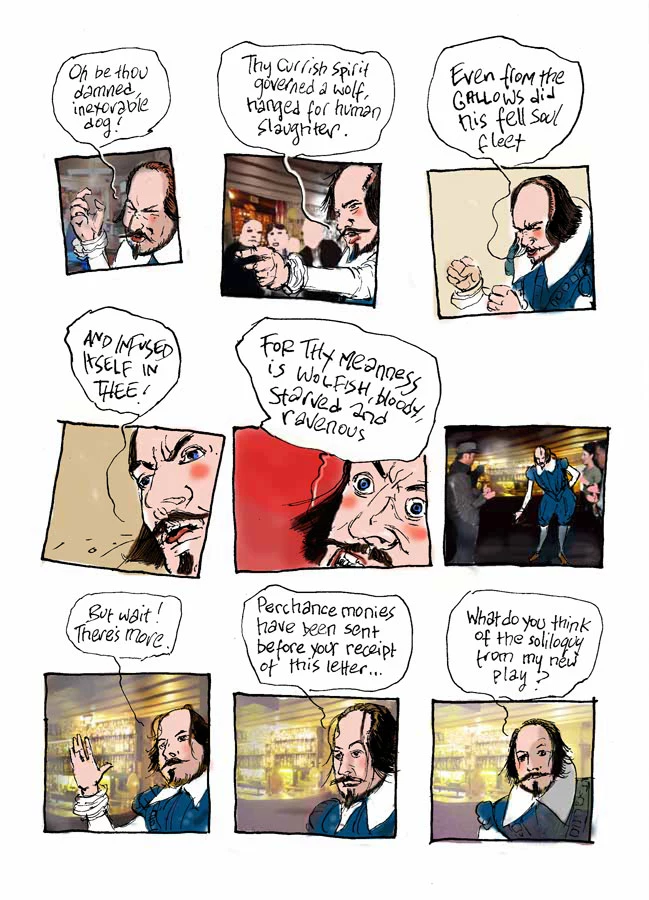

Like How To Be an Artist, there are some comics industry behind-the-scenes moments that are as dumbfounding and entertaining as the industry itself. As a self-publisher, Eddie dictates hilariously pointed and borderline-sociopathic letters to late payers; as a freelancer, he has to go through the nightmare of forming a corporation just so he can write and draw Batman: The Order of Beasts. At one point, Campbell is deep in development on a television show based on After the Snooter and family life, only to have it yanked out from under him by the 2008 financial crisis. It's comedy in the greatest Shakesperean sense. The bard even makes an appearance, dictates his own barbs to the faulty, and headbutts a television producer. Literature!

The two stories that dominate the book, though, have little to do with the creative life. In a time when the tightrope is bounding skyward, Eddie makes the uncharacteristic move of lending a large sum of money to his father-in-law. It doesn't work out, of course, and the end result is the effective estrangement of his wife's father from the family. Even after all of the frightfully honest work in Campbell's biographies, the candor he uses in relating the story feels like something new. Campbell recognizes the similarities between himself and his in-law, and braces himself for the possibility that his own stubbornness will one day find him in the same position.

The last portion of the book tells of Campbell's vacation to the Micronesian island of Yap, and its unique system of discerning wealth. For hundreds of years, the Yapese have used carved stone discs to denote wealth, ranging from a foot or so across to more than ten feet. And though the rai can be used to buy things, it doesn't necessarily have to change hands; it stays displayed outside the carver's home. Campbell hints at something really interesting here: in a way, the money itself is like intellectual property. It's a product of creativity and imagination; as long as it exists, it represents a source of income, and though the owner of the stone changes, it will always be recognized as the creation of the carver. It can even be used to buy another tribe's dance, another intellectual property.

As a writer, Campbell has always been freakishly natural, and he continues to progress. The Lovely, Horrible Stuff is enjoyable on so many levels: the mundane daily grind, the wacky family life, encyclopedic dissertations and history lessons, and riotous moments of un-reality all thread together in his easy, poetic voice. As an artist, the man has probably never been more relaxed. After working in black and white for so long, he appears to be deeply in love with color now, utilizing bright photo backgrounds and watercolor like never before. He shifts from loose sketches to hard realism to kooky explosions of icons without ever breaking his easy rhythm.

While writing about the island of Yap, Campbell spends a few pages ruminating on fables and legends, perhaps he's aware of how parable-like his own life has become. Over the course of thirty-plus years, he's recounted mad adventures and, whether he intended to or not, passed valuable lessons on to his readers. Generous with his wisdom but quick to point out how unwise he is, he is both the storyteller and the story, entering the fourth decade of his career with a book on money that's lively, poignant, and never dull. Tight as times are, The Lovely, Horrible Stuff is worth every hard-earned penny you can find.

Read a 7-page preview of The Lovely, Horrible Stuff:

More From ComicsAlliance

![Comic-Con: The Publisher Booths [SDCC 2013]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2013/07/sdccpublishingboothsmain.png?w=980&q=75)

![‘Nemo: Heart of Ice’ Is ‘The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen’, Streamlined [Review]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2013/02/nemoreviewmain.jpg?w=980&q=75)