Making It Plain: U.S. Rep. John Lewis Discusses His New Civil Rights Graphic Novel, ‘March: Book Two’

With the publication of March Book Two this week, U.S. Rep. John Lewis and collaborators Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell continue to tell the tale of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s from a personal, relatable perspective.

In the year and a half since the publication of March Book One, the graphic novel has won awards including the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, and has become a classroom teaching tool for students in elementary school all the way up to college age. It's a remarkable work by and about a remarkable man, and ComicsAlliance was lucky enough to speak with Rep. Lewis about why he chose to tell the tale via graphic novel, the book's depictions of violence, forgiveness, and much more.

ComicsAlliance: Those of us who didn't live through the civil rights movement of the '60s and only know about it from history books and TV haven't gotten a lot of personal perspective on it. That's one thing that March has. One of the things I was really struck by were personal stories of yours about being worried about getting back to school in time to do the things you needed to do at school, or eating at a restaurant for the first time, or going to New York for the first time.

What drove you to want to include those little personal elements of the story in the book, along with these huge historical moments?

John Lewis: More than anything else, it was my desire, along with Andrew as co-writer, to make the book as human as possible. To tell the story, the personal story. I'm saying that I don't have any extraordinary gifts. I'm just an average Joe who grew up very poor in rural Alabama. I was someone who didn't like what I saw and came out of the influence and teaching of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks. I wanted to do something about it. It was important that I went to Buffalo, NY the first time when I was 11 years old in 1951. My first time eating in a restaurant was in Nashville, Tennessee, as a student being segregated in restaurants at lunch time. The first time having Chinese food when I came to Washington DC, the first time in 1961, to go on the Freedom Ride.

It tends to humanize the book but also to get the readers, especially young people, to know what I felt and what I experienced as a child, and what we did. We grew to accept nonviolence as a way of life and as a pursuit. We did not deviate from this philosophy. We went to be beaten, to suffer, to go to jail. When we went on the Freedom Ride, we were willing to die for what we believed in.

CA: You mentioned young people, and one thing that's happened since the publication of Book One is it has become a teaching tool. It has become something that has been used in classrooms as a way to teach about this period of time and what took place.

JL: We're very pleased that teachers and libraries are using the book. Several universities have made it required reading for freshman students. People are teaching March in schools in more than 40 states. But you go to a place like Michigan State University, they made it required reading for more than 8,500 freshman. Georgia State made it required reading for more than 3,000 students. Marquette made it required reading for their freshman.

CA: Did you have that expectation as you and Andrew and Nate were collaborating on this? That the book would be used this way, beyond for leisure reading?

JL: We wanted as many people as possible, but especially young people to pick this book up and read it, to be able to say, this is the way another generation was able to accomplish something.

You go to a book signing and people bring their little children, and I've seen it on more than one occasion: When you sign the book, a child will take the book and go and sit down some place by themselves at a table, and read it. Then they'll walk up to us and say, "I just finished reading the book," and they ask, "When will Book Two be ready?"

I think many people -- in elementary school and middle school, high school age and some in college -- they want to know, and it's easy and simple to read. With the artwork and the words, the book is made plain. It reminds me of what Dr. King's father would do when he was preaching sometimes at the church in Atlanta. When Dr. King would be preaching, his father would say, "Make it plain, son. Make it plain."

So March Book One and Book Two have the capacity to -- with the writing, but also the artwork -- to make it plain to make it simple, to make it complete. That's what you have to tell, not just part of the story but the whole story.

CA: Book Two in particular doesn't shy away from at all is some rather disturbing depictions of violence. These are things that really happened, and I understand why those things are there, depictions of people being smashed in the head with batons and various things. The Freedom Riders' bus being set on fire. What discussions did you, Andrew and Nate all have about how to depict the violence to make sure people a sense of what really happened but maybe not to go too far with it or seem to be too graphic?

JL: We didn't want to shy away. We didn't want to hide anything or sweep something under the rug or in some dark corner. It's real. We used the N-word. We had some discussion about it, but it was important to make it plain, to say what happened, describe it. In Montgomery, when we arrived for the Freedom Ride, I was hit in the head with a Coca-Cola crate. That's what happened. I was there for a while with a bloody head. Apparently, I lost consciousness.

We wanted to tell the complete story, the whole story. I think for some people, it's painful to see the images and to read the words, but I think the three of us felt it was important to complete it and not to sugarcoat anything or leave something out.

CA: When I spoke to Nate at Comic-Con back during the summer, he told me one scene that really affected him greatly is a scene that happens in Book Two where a mother is encouraging a young child to attack someone's eyes.

JL: Yeah.

CA: One thing that I certainly felt reading Book Two was just this feeling of anger at these people from 50-plus years ago. How do you depict these folks without making them fully evil? I know that you really advocate for forgiveness and forgiving people. People change. But just seeing what these people did is so horrifying.

JL: You still have to have the capacity and the ability to take what people did, and how they did it, and forgive them and move on.

We had a young man several years ago, in February, 2009, who had beaten us at the Greyhound bus station in Rock Hill, South Carolina. He came to my office with his son -- he was in his seventies, son was in his forties -- and said, "I wanted to meet you. I wanted to apologize. Will you forgive me?" I said, "Yes." His son started crying. He started crying. They both hugged me and I hugged them back and I saw him three other times. That's the ability and capacity to recognize the dignity and worth of every human being. That's what we're trying to do in Book One as well as Book Two.

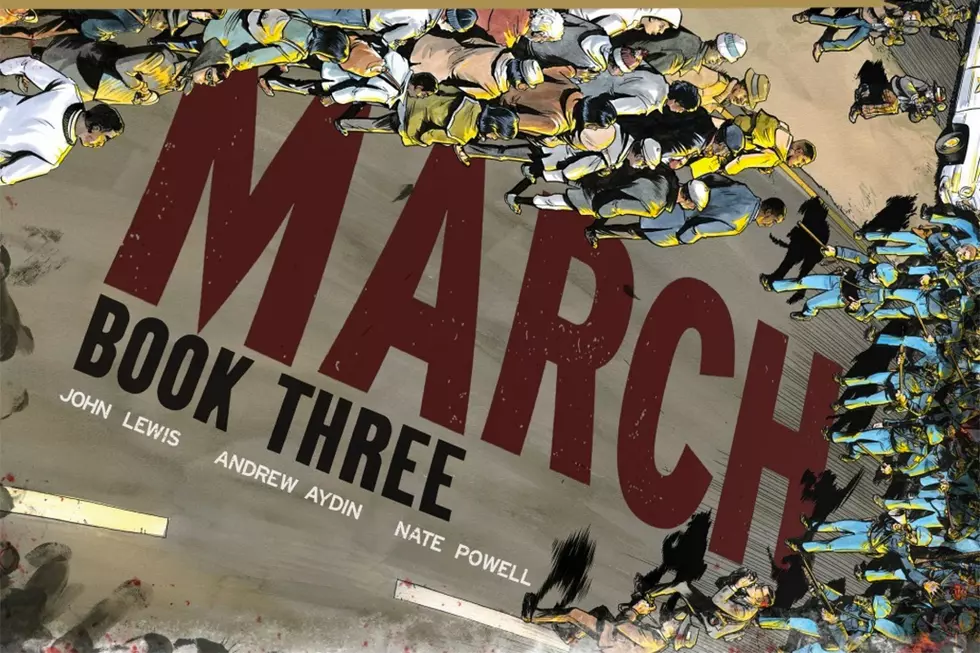

CA: The events that took place in Rock Hill are in Book Two. Is the plan for Book Three, then, to circle back to how you did forgive some of the people who did these horrible things? Book Two culminates at the March on Washington with your speech and Dr. King's speech. It's this big moment of soaring rhetoric, but the book actually ends with the church in Birmingham exploding, which shows that it's not over. There's still so much hatred.

JL: Yes. After the March on Washington, we moved on to Selma and [the] Mississippi Summer [Project]. I know what happened, something better did emerge with the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the election of President Barack Obama. It's story that will continue to evolve until we get to a better place, and until we get to what Dr. King called "the essence of a beloved community," where we see each other as one family, as brothers and sisters living in one house, the American house. The world house.

CA: I wanted to ask, since you brought up President Obama, what made you decide to frame the events of the story with those interstitial scenes of you attending President Obama's inauguration? Why did you want to intercut these events from 50, 55 years ago with the inauguration?

JL: Andrew saw me speaking and talking to young people the morning of the inauguration. There was a mother and her children who came by the office, and I was telling a story of civil rights movement. He felt that it shouldn't just be limited to the people coming into the office. He said I should tell these stories to others and that's what we started doing, trying to just tell stories and I remember the day of the inauguration in '09. The president, after he delivered his inauguration address, signed an envelope with his likeness on it. He wrote, "Because of you, John, Barack Obama." Then I saw him in '13 and he said to me, and he remembers it so well apparently, "It's still because of you, John." I said, "Thank you Mr. President."

CA: Congressman, what's your background in terms of reading comic books and reading graphic storytelling? Have you been a fan of comics through much of your life, or is a lot of this new to you?

JL: I grew up with six brothers and three sisters. I grew up in a household and a neighborhood in rural Alabama where people told stories. We didn't have that much money to buy comic books, but the paper that we would get on the weekend had comics. We would read that. I have a younger brother who loved comics. Even when he got up as an adult, he would watch, when we got a television, he would watch cartoons and we'd just laugh and carry on. He got excited about it.

What really turned me on I think was Martin Luther King, Jr.'s The Montgomery Story that I started reading. It was drawings of people doing stuff, of Dr. King speaking, Rosa Parks sitting down, people organizing the bus boycott. I saw people doing something that was action.

CA: I think that once you finish Book Three you might have a second career on your hands. You, Andrew and Nate might want to sit down and think of another graphic novel series to do because, March has been really good.

JL: That's a good suggestion. I'll talk to Andrew about it. Thank you.

March Book Two goes on sale this Wednesday in comics shops and bookstores from Top Shelf.

More From ComicsAlliance