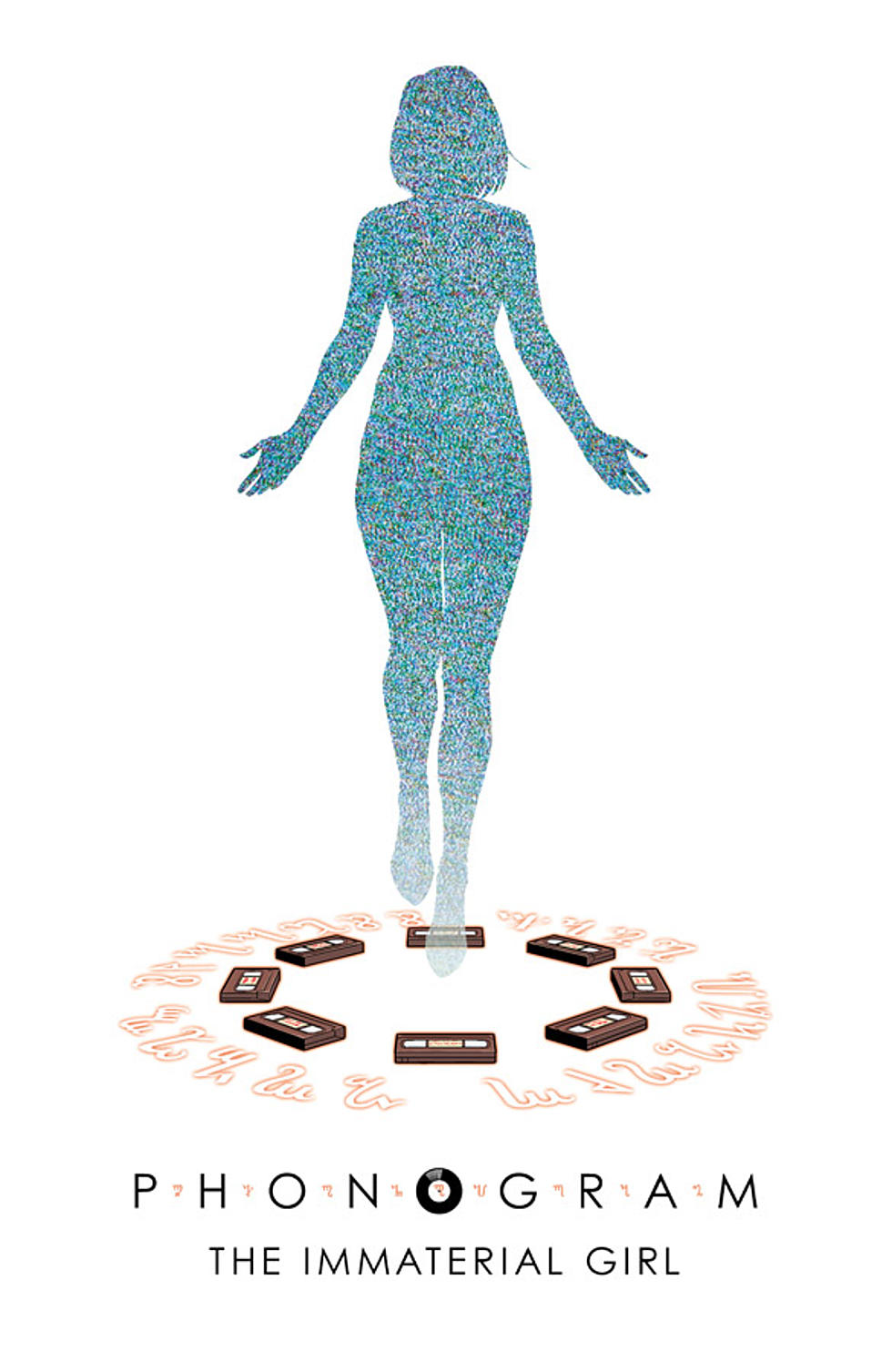

The Bleakness + The Delight in ‘Phonogram: The Immaterial Girl’

Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie are probably now best known for their Image series The Wicked + The Divine, set in a world where popstars are gods. Their other Image sieres, Phonogram, is set in a world where music is magic. The two books have a similar premise, and deal with some of the same ideas and themes, but they attack them from completely different angles.

While The Wicked + The Divine is about making art, Phonogram is about consuming it. The former is about being young and deciding to give up your life to music, but Phonogram – and The Immaterial Girl in particular – is about living with the consequences of that deal. Not burning out in your early twenties, but fading away into middle age, with a great record collection instead of a family.

That might sound a bit miserable --- and there is a 'but' coming eventually --- but it has to be said that Phonogram: The Immaterial Girl really does know how to stick the knife in.

The immaterial girl of the title is Emily Aster, a phonomancer – someone who draws magical power from music – who stripped away half of her personality to become something simpler and happier and more attractive. From a Smiths B-side to a Madonna single, to put it in Phonogram terms.

As anyone who's read Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, or a comic with the Hulk in it, will be able to tell you, trying to repress half your personality rarely comes without consequences. In this case, Emily's emo alter ego wants her life back, mostly so that she can destroy it. Both figuratively, by brutally dismantling Emily's friends and peers, and physically, through self-harm. And actually, that's a pretty good metaphor for what the comic does to the rest of its cast.

At the edges of Emily's story, we get to see some of the others characters the series has accumulated over the past decade: David Kohl, Gillen's semi-autobiographical stand-in from 2006's Rue Britannia; His friend and occasional sidekick Kid-with-Knife, a hip hop fan without much use for this music-is-magic nonsense; Lloyd and Laura, representing the younger generation of phonomancers we met in the second series, 2009's The Singles Club.

It's nice to see these familiar faces again, but The Immaterial Girl isn't afraid to be critical of its cast. And chances are, at least one or two of those criticisms will land close enough to the bone that reading them hurts. I mean, look at these two pages:

That's Lloyd up there. Picking up two years after The Singles Club, he's now working in a chain pub, reliving an old argument with Laura that we saw in that series. Two years, and he still remembers it with cutting clarity. We've all got a few of these moments that haunts us, I'm sure – but seeing Lloyd continuing the argument, putting fresh insults in Laura's mouth, makes me shudder with recognition.

And these are the young hopefuls of the series. Meanwhile, the rest of those familiar faces are ageing fast (Kohl's hairline is arguably the real victim of this series) and continuing to make the same mistakes, at an age where they start to look unseemly.

I promised you a 'but', though, and here it comes...

But Phonogram is also a comic full of joy!

It's a comic about and by people who truly genuinely love this music, and that has always shone through. The very first issue featured a lengthy tribute to Kenickie that had me falling in love with the band before I'd heard a single note. In The Singles Club, McKelvie drew characters dancing in a way that helped me get over my shyness about throwing shapes in public.

The Immaterial Girl is packed with moments of sheer joy, most of them courtesy of McKelvie and colourist Matt Wilson, who bring their usual effortless A-game. With Emily trapped “behind the screen” – an MTV-does-Battleworld astral plane stitched together from '80s music videos – the plot gives both opportunity for some remarkable experiments.

There are segments rendered entirely in the animated bare-pencil style of A-Ha's “Take on Me” video, and one double-page spread that turns a collage into an obstacle course. TV static is dropped in as page backgrounds, with panels and even characters carved out of the white noise, while letterer Clayton Cowles provides closed captions.

That same playfulness is there in those Lloyd/Laura pages that I pulled a sad face about earlier. The static face Lloyd is arguing with in his head is a panel plucked straight from The Singles Club, and the scene resolves with Lloyd reaching out of the comic to pluck the panel from the page, in a way that's reminiscent of both his own issue of that series and another focusing on two DJs, foreshadowing the rest of this comic. Oh, and as you may have noticed, it's all in black and white because this scene comes smack-bang in the middle of an issue-long homage to Scott Pilgrim.

It's enough to make your head spin, and that's before you even get to the arguments about the importance of image versus meaning, the mutability of personality, the kneejerk backlash to popular bands, and the thousand other things the series is weighing up. At its best, reading Phonogram is like having a conversation with a friend who's smarter than you, the kind that keeps spooling out until the pub starts to close around you.

Naturally, the talk turns a little dark at times, to ageing or death or whether we're wasting our lives. The Immaterial Girl is smart enough to understand that light without shade is meaningless. Which is also what Emily's story is all about: the realisation that rejecting one half of your nature condemns you to a two-dimensional version of life. The kind you'd experience if you were, say, trapped in an A-Ha video.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Bond After Brexit: Kieron Gillen Declassifies ‘James Bond: Service’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Service_McKelvie-feat.jpeg?w=980&q=75)

![Comics’ Sexiest Female Characters (From A Queer Perspective) [Love & Sex Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/02/hg_featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![The Hero We’ve Been Waiting For: ‘America’ #1 By Gabby Rivera And Joe Quinones [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/02/America_1_Featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)