Thought Bubble #4: What ‘Age’ Of Comics Is This?

The comics medium attempts to answer a lot of big questions: What makes someone truly evil? What's wrong with childlike wonder? How, father? How do I do it? What do I use...to make them afraid? In that spirit, ComicsAlliance's Matt Wilson is asking comics creators, retailers and commentators some big questions of his own.

In this installment, comics researchers and scholars Douglas Wolk, Ken Quattro, Derek Royal, Andrew Kunka and Charles Hatfield and answer the question: If we've seen the Golden Age, the Silver Age, and the Bronze Age, then what would you call the current "age" of comics?After the Golden (the mid-to-late 1930s through around 1950) and Silver (the mid-1950s through around 1970) ages, general consensus on which age is which pretty well breaks down. Many say the Bronze Age runs through the 1970s up through the mid-'80s, but even when that ended is up for debate. Some call the age right after that The Dark Age, while others call it The Copper Age. Some call the mid-to-late 1990s the Image Age or the Chromium Age. I've heard the current age called The Second Golden Age, The Prismatic Age, and The Second Dark Age.

It's a moving target, but I tried to get the best handle on it I could by asking a few comics historians and scholars to weigh in, not only with their best guess as to the current age of comics, but to also throw in their two cents regarding what purpose having ages serves for fans, retailers and researchers.

Douglas Wolk (Author of Reading Comics):

I like the idea that the lower-case "golden age" of comics is now, and I think there's still every reason to think it's true -- maybe especially since one of the big problems that's always faced comics readers is availability, and now nearly every comic ever printed is at least sort of available to anyone on the fortunate side of the digital divide, and most of the best older ones are appearing in more durable physical forms, too. Even in terms of new material that's available every week, there are more things that anyone who's interested in almost any aspect of the medium is going to want to read than there have ever been before. I can't even keep up with everything I'm pretty sure I'm going to enjoy, which surprisingly turns out to be a great feeling. This is a season that's giving us Building Stories and Casanova: Avaritia and Bandette and The Zaucer of Zilk and Journey Into Mystery and The Making Of and Diesel Sweeties 3000 and Snarked!, just off the top of my head, a couple of which are appearing in forms that wouldn't even have been possible a few years ago.

That said, I don't think it's necessarily fair to the present moment to draw a border around it. Unless there's a particular style or ideology going around, and I don't know of a particularly big and exciting emerging one in comics right now, it's much easier to understand what's happening in a particular moment of an art form from a distance. The moment you put a name on the aesthetic of a time and place, you give smart artists something to rebel against, and less smart artists something to ape ineptly. We'll figure out what age we're in once we're out of it.

Ken Quattro (Of The Comics Detective blog and Comicartville, where he re-examined comics ages):

Being perfectly honest, I no longer follow today's version of comic books. I began to lose interest in the mid-'90s when the "grim and gritty" comics came to dominate and the heroes I grew up with became passé. That said, I'd offer that we are seeing the Boutique Comics Era, a time of specialized interests rather than one predominate genre such as superheroes. Then again, we are likely experiencing the fading of print comics and the advent of e-comic books. The print books are not long for this Earth and if comics are to survive, it will only be in this form.

[Having ages is useful because] it provides structure; a framework that divides comic book history into understandable chunks that can be defined by any criteria the user devises. I use editorial content to describe my "ages." Others use price changes or metallic contrivances to define theirs. I'll leave it to future historians to decide upon the definitive eras. I'm content with mine.

Derek Royal (English instructor at Southern Methodist University and co-host of The Comics Alternative podcast):

I don't really feel the need to define or "finger" the current moment in comics history, that is, outside of just calling where we are right now "contemporary," which, I'm aware, is not very descriptive at all and rather ambiguous outside of the temporal implications. I have no problem with earlier designations such as "gold," "silver," etc., but I think of them as very loose groupings with no distinct boundaries. As you know, there is some debate as to which era ended and which began, so in that sense such temporal or historical naming doesn't serve us completely. Still, there is a need for "historical groupings" that provides us with a sense of evolution and development in the medium. If I can bring in my disciplinary background for a moment, the "comics age" question is akin to what we do in literary studies regarding periodicity. For example, where does "romanticism" or "modernism" begin, how does the answer differ depending on what cultural/national contexts you consider, how much of it depends on the most popular or the most canonical authors, etc.? In fact, discussions of how to define the current literary moment -- is it something like post-postmodern, should we call it postcolonial, a new realism? -- have similar problems. It depends on what texts or authors you look at, what genres, and such. In many ways, it's impossible to define the current moment when you're standing in the middle of it. Give it a good 50 years, and then see what folks are saying.

There are some in comics studies who want to chunk the entire gold/silver/bronze stuff entirely. If you check out [Randy] Duncan and [Matthew J.] Smith's The Power of Comics, you'll see that they are of this mind and have come up with their own historical markers. I'm not sure if this is any more useful than traditional and fan-based designation, but I mention this as one alternative to the golden age, etc.

Personally, I'm okay with being ambiguous and uncertain about the current moment in comics. I just want to enjoy it, experience it in its many and diverse forms, and just get a feel for all of the great stuff out there. I really don't think we gain much by forcing a name or specific characteristic onto the medium as we are experiencing it now. We also have to keep in mind that what one person might be perceiving primarily through the superhero genre may be vastly different from what a comics reader perceiving things primarily through autobiographic or memoir comics (which are mostly the "rage" in academia) or through crime/noir comics or purely through the prism of independent/alternative comics.

Andrew Kunka (Professor of English at The University of South Carolina Sumter, the other co-host of The Comics Alternative podcast):

If you are looking for a "scholarly" perspective, my first impulse would be to problematize the concept of "ages" in comics. That is, the concept has only limited scholarly/historical relevance, as it requires significant qualification in terms of limitations and exceptions. The separation of a Golden Age from a Silver Age in comics was originally performed by fans, collectors, and dealers, partially out of nostalgia but also out of a practical desire to define the market for back issues. However, even in that context, the Golden and Silver ages only really define most superhero comics from those historical periods. For example, humor comics, especially funny animals, remain unaffected by any changes that take place in the superhero genre from the late 1950s to early 1960s, and it would be difficult to define cartoonists like Carl Barks or John Stanley as Golden or Silver Age creators.

That being said, the comics fan in me still finds the idea of defining ages of superhero comics -- or "Heroic Ages," as Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs call them in The Comic Book Heroes -- compelling, especially as a means of identifying major trends that are influencing comics creators and fans at a given moment. And by "major trends" I mean that not everything in superhero comics today will neatly fit into any definition of the current age. Also, it can be a fun mental game to play.

Therefore, with all that qualification in mind, I find the concept that defines the current age -- the post-Dark, post-Image, post-Chromatic, post-whatever age -- best for me is the "Prismatic Age," which was originally identified on the excellent Mindless Ones blog and also discussed by Grant Morrison in Supergods. In sum, the Prismatic Age is defined by a series of reflections and a proliferation of different versions of the same concept, often as a nostalgic look back a the past rather than a revision or dismantling of accepted superhero tropes.

After the master superhero narratives were dismantled by Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Warren Ellis, Mark Millar, Joe Casey, etc., what was left for comics creators was an often nostalgic reflection on the past. For fans, this reflection often manifested itself in a conservative desire for the familiar; hence, the popularity of big events that are reflections of past events, and lead themselves into the next event, and so on, endlessly. In addition, corporate brand and IP protection encouraged repetition, stability, and "consequencelessness."

But if this is the Prismatic Age, we are probably at the tail end of it. DC's New 52, for the most part, seems to be the resulting consequence of reflection upon reflection upon reflection. It's a reboot, yet one which still requires some knowledge of the past comics being reflected. The new Earth 2 may be the ultimate example of the consequences of endless reflection: the new Jay Garrick, Alan Scott, Al Pratt, et al, are not so much reflections of their Golden Age selves but are instead reflections of the current incarnations of those given heroes, who, on their world, take the place of reflections of Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. In other words, the reflections have come full circle. This latter point is what makes the Mindless Ones' concept so compelling: "Botswana Beast" wrote the post in 2008, but it has borne itself out in the years following. And if we are at the end of the Prismatic Age, then something, perhaps tied to digital distribution and the tablet format, is currently slouching toward Bethlehem to be born.

Charles Hatfield (Associate professor of English at California State University Northridge, author of Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby):

To be honest, this is a bit of a vexed question for me. In Hand of Fire, I did use the terms Golden and Silver Age. Frankly, I found it difficult not to use them, even though I really did try not to. I realized I had to use those terms from time to time, because, one, they are familiar canonical terms among collectors of periodical US comic books, particularly superhero fans. Two, I was writing a book that, as it turned out, had a lot more to say about superheroes than I had anticipated. So I had to have recourse to the terms that fans and collectors use.

The Golden and Silver Ages are important signposts for superhero fandom, and the distinction between the Golden and Silver Age is clear enough as long as the context of discussion is periodical superhero comic books. But the problem I have with these terms -- and I really do believe it is a problem -- is laid out well by Ben Woo in his essay "An Age-Old Problem: Problematics of Comic Book History." Ben's argument lays out several difficulties with the age concept. In my mind, the principle difficulties are two:

First, the ages concept is too superhero-centered to accurately cover the entirety of comic book history. Recall that the ages were defined by superhero collectors and fans. In fact the Golden Age was defined retrospectively during the Silver; the concept of the Golden makes no sense without the Silver. The revival of superhero properties by DC after 1956 and Marvel after 1961 was encouraged by the rise of a self-conscious superhero comics fandom centered around nostalgia and collecting. Bill Schelly's book The Golden Age of Comic Fandom is useful here, as is Matt Pustz's Comic Book Culture. Those fans egged on the editors at DC and Marvel, spurring the superhero revival, and it was those fans who established the Golden and Silver Ages as common terms. To these fans, the superhero was the basic measure of comic books -- the one native and crucially important genre in the medium's history. But I don't agree with that. The superhero was actually dormant, nearly a dead genre, in the late 1940s and early 1950s -- when the overall sales of comic books were at their peak!

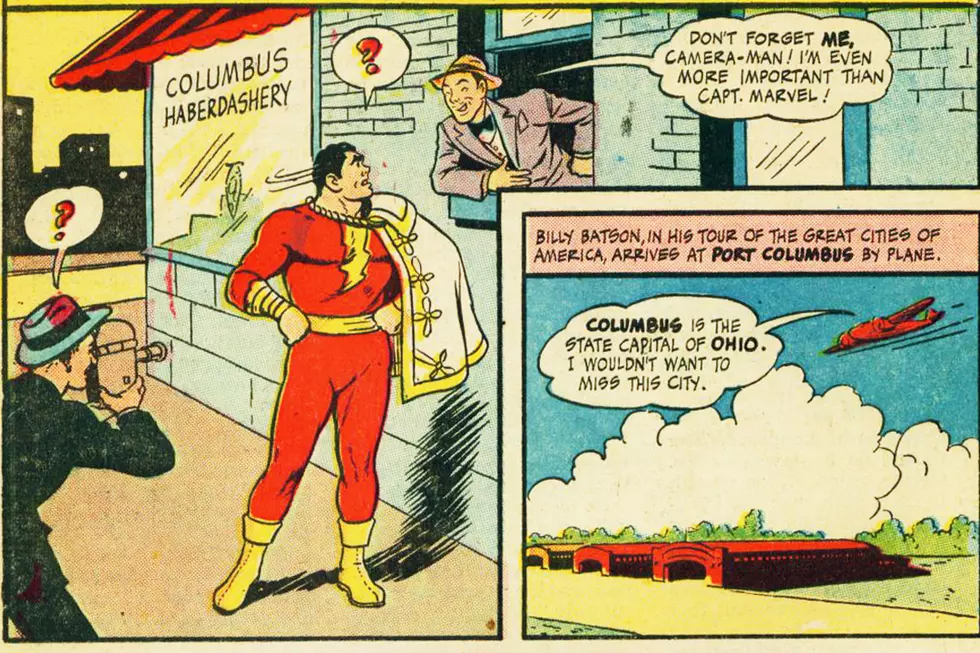

Throughout the postwar years, and certainly from about 1947 to 1948, all the way up to the early '60s at least, the superhero was not the dominant genre. So many other genres--funny animal and children's humor, Archie-style "teen" humor, romance, satire, the western, war comics, horror and crime comics, jungle comics, literary adaptations, etc.--helped to grow the comic book industry and account for much of what is interesting about its history. A superhero-based ages system is inadequate for addressing those complexities. For example, if we say that the Golden Age started with Superman and then persisted into the late '40s or even into the 50s, we are eliding the crucial differences in the market between, say, 1940 and 1950. The age concept applies only to superheroes, and even then is problematic because it does not acknowledge the way other genres influenced the superhero, e.g., the way romance comics influenced the Marvel superheros of the '60s.

Second, I don't think it's sensible to insist that an age begins with a specific publication, even if superheroes are one's main focus. For instance, if we insist that the Silver Age began in 1956 with DC's Showcase #4, reintroducing the Flash, then we have to ignore or downplay the Martian Manhunter's debut in 1955, or Atlas's revival of the Timely superheroes a bit earlier. It takes trends and systemic changes to really mark out a new era. One comic book, however successful or however significant in hindsight, cannot launch an age. If we must periodize comic book history, then we should do so based on economic and publishing history rather than the appearance of particular characters or titles or the supposed changes in tone or spirit that come with a new age.

Events such as the creation of the CMAA [Comics Magazine Association of America] and the imposition of the Comics Code, the advent of direct market distribution circa 1973, the monopolistic narrowing of the direct market in the mid-9'0s, or the more recent consolidation of Marvel and DC with larger corporate entities are much more important boundary markers, in my opinion, than the appearance of a single title or character or genre. So, I'm against perpetuating the ages system in general. And even though I've used the Golden and Silver Age terms when studying Kirby and superhero comics, I don't use, cannot bring myself to use, other terms like Bronze Age, Modern Age, Prismatic Age, etc. I see no use in those terms, and I don't think they've inspired the same degree of consensus as Golden and Silver. "Bronze" is widely accepted, maybe, but it doesn't work for me.

If we had to give a name to the current period in floppy comic books, I'd say call it the Mega-Corporate Age, but even that would be useful only in a very limited sense, because it would only apply to direct market and downloadable DC and Marvel and their nearest competitors, whereas much of what is interesting artistically about comic book culture has in fact migrated out of periodical comic books altogether, into graphic novels, Webcomics, minicomics, and other channels. One has to be very precise about periodization, and acknowledge that it only works in particular contexts. The context in which terms like Prismatic Age or Dark Age would work doesn't really interest me, and I think future historians, with the benefit of hindsight, will be looking elsewhere.

Thanks to everyone for their thoughtful contributions. And now we put the same question to ComicsAlliance readers: what 'age' of comics is this?

More From ComicsAlliance

![Golden Age Superheroes Return in ‘Not Forgotten’ [Back Pages]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/02/notforgotten-featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)