Wonder Woman: A Look at the Controversial 1970s Take on the Amazon Princess

Buzz and controversy have been swirling around Wonder Woman a lot these days. The politics of retcons and reboots have thrown interested parties into an absolute tizzy over the lineage, age, and even the fashion sense of the original super-heroine. The looming post-Flashpoint status of the character, pants or no, is sure to be another in a long line of questioned portrayals and continuity shoehorns -- from J. Michael Straczynski's Americanized teen to John Byrne's "Goddess of Truth" and beyond.

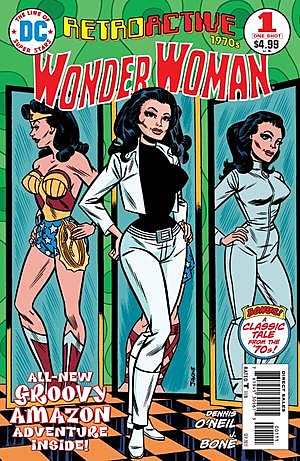

Perhaps in anticipation of this, DC Comics today releases Wonder Woman: The 70s, a new look back at yet another controversial turn in her history, as part of the DC Retroactive line.This may turn out to be a useful strategy. Because as controversial as the new Wonder Woman may be, it's doubtful that it will live up to the fervor surrounding Denny O'Neil's well-intentioned take on the character in the 1970s...Look, the '70s were a crazy decade, okay? There was a gas crisis, a nation searching for its identity after Vietnam and Watergate, coke was suddenly everywhere... Wonder Woman's "lost decade" is certainly much less severe than, say, Sly Stone, but despite the lack of any illegitimate children or visits to rehab, comics luminary Denny O'Neil displays a fair amount of shame about the whole thing. Chances are, if you're the type to watch History channel documentaries or listen to podcasts about comics, you've seen or heard him apologizing for it.

"I thought I was on the side of feminism," he says in this clip, shrugging his shoulders like a top-notch Woody Allen impersonator. And according to an extensive interview with LanternCast, he does in fact view a new story on the character as an opportunity to redeem himself. What did he do that was so wrong?

"I thought I was on the side of feminism," he says in this clip, shrugging his shoulders like a top-notch Woody Allen impersonator. And according to an extensive interview with LanternCast, he does in fact view a new story on the character as an opportunity to redeem himself. What did he do that was so wrong?

When O'Neil assumed scripting duties for Wonder Woman in 1969, he was one of the most forward-thinking writers in the field. Like Stan Lee and Dave Sim, he's always been a bit of a preacher, willing to use his art to express moral or political ideals. Of course there's the classic example of the socially conscious Green Lantern/Green Arrow, illustrated by another preacher, Neal Adams, where O'Neil chiseled away at class divisions, racial divides, and the inherent injustice of the system. Even in Batman, again with Adams, O'Neil funneled his frustration with environmental issues through the eco-terrorist Ra's al Ghul. So when DC provided O'Neil the opportunity to update Wonder Woman for the Women's Lib generation, he undertook it with an altruistic approach, under the guidance of artist and master storyteller Mike Sekowsky.

Everybody seems to forget that Wonder Woman's transformation from Amazon to modern girl was the brainchild of Sekowsky, an illustrator and storyteller of the highest order. Hoping to encourage female readers to strive for independence, Sekowsky, DC, and O'Neil stripped the character of her powers, her lasso and bracelets, and her red-white-and-blue costume, and made her a strong, intelligent working woman who also happened to be a superspy of the highest caliber. You have to admit, it's not a bad idea.

Within the first few issues of their run, Wonder Woman renounces her mystic skills and lineage as granddaughter of Ares (an origin point that wasn't added until the late '50s), giving up her powers and embracing the identity of Diana Prince, boutique owner, martial artist, and all-around adventurer. And frankly, she's not a bad example for anyone, male or female: she's smart, self-reliant, loyal, and fearless, and giiirl, she know how to dress!

Though O'Neil and several others have denounced this version of the character and the resulting work, there's little negative that can be said about Wonder Woman's new look and the dynamic draftsmanship that Sekowsky brought along with it. Visually, "The New Wonder Woman" (issues 178-190ish) is pretty stunning. Sekowsky is a firecracker layout artist, throwing all the momentum he can into the action, with vertigo-inspiring slash panels and creative cuts. The attention to the look and style of Diana's clothing is impressive: She settles on sleek Bruce Lee-style unitards for action, but in life she wears all the modern fashions, all the marvelous little pieces of pop art that populated the industry in the '60s. Again, Sekowsky's work is gorgeous, as Romance comics, ad design, and a hint of Steranko inform the interpretation.

Though O'Neil and several others have denounced this version of the character and the resulting work, there's little negative that can be said about Wonder Woman's new look and the dynamic draftsmanship that Sekowsky brought along with it. Visually, "The New Wonder Woman" (issues 178-190ish) is pretty stunning. Sekowsky is a firecracker layout artist, throwing all the momentum he can into the action, with vertigo-inspiring slash panels and creative cuts. The attention to the look and style of Diana's clothing is impressive: She settles on sleek Bruce Lee-style unitards for action, but in life she wears all the modern fashions, all the marvelous little pieces of pop art that populated the industry in the '60s. Again, Sekowsky's work is gorgeous, as Romance comics, ad design, and a hint of Steranko inform the interpretation.

Over the course of a couple years, reaction went from mixed to negative to staunch opposition presented in letter form in a national publication. Hey, any mainstream reaction is good, right? Gloria Steinem, principal icon and activist of the Women's Liberation Movement, the very movement that Denny O'Neil was trying to show his support for, published an article in Ms. magazine arguing that it was in fact an anti-feminist interpretation. And she and other detractors weren't without a point.

Steinem argued that O'Neil and Sekowsky failed the moment they removed her powers. As Diana Prince, she was a powerless woman learning martial arts from I-Ching, mysterious master that he may be, he's still a man. As Wonder Woman, she was stronger than men. Better than men, from a society untouched by the wars of men. By removing her advantages and her Amazonian traits, they had dulled the impact of the character, reducing her from goddess to an average gal living in a man's world.

Wonder Woman is a unique invention. Other iconic characters, Superman and Batman, can be dissected to show Jungian traits and patterns consistent with the uber-myth. Unintentional traits. Wonder Woman was created with direct knowledge of these concepts, and intentionally imbued with those traits. Created by psychologist/lie-detector inventor/three-way marriage havin' sonofabitch William Moulton Marston, Wonder Woman was specifically designed to spread WMM's philosophy: that the world would be a better place if women were running it. While setting a strong example for girls, Wonder Woman also enticed and entrapped boys with suggestive scenes, bondage fantasies, hot 1930s girl-fight action, and frequent reminders that penis = death.

Point being: there have always been totemic qualities in Wonder Woman's story, ambiguity in her presentation as simultaneous feminist icon and male fantasy, and as the first woman superhero, she has always been a mechanism of the portrayal of women in America. Modernizing her and realizing her wasn't a bad idea, it was just improperly executed. O'Neil and Sekowsky's work isn't bad - it's shiftless at times, unsure of what it wants to be, and written with the fingers of a man trying to tell women how cool he is with the whole Women's Lib thing. (No offense, comics legend.) There are several interesting things happening in the work: Its independence from the DC Universe, the astounding visuals of Sekowsky, the ten years early introduction of the comic book "realism" of the 80s. But ultimately the whole event is the comic book industry equivalent of a husband unsure of what he did to piss off his wife.

Point being: there have always been totemic qualities in Wonder Woman's story, ambiguity in her presentation as simultaneous feminist icon and male fantasy, and as the first woman superhero, she has always been a mechanism of the portrayal of women in America. Modernizing her and realizing her wasn't a bad idea, it was just improperly executed. O'Neil and Sekowsky's work isn't bad - it's shiftless at times, unsure of what it wants to be, and written with the fingers of a man trying to tell women how cool he is with the whole Women's Lib thing. (No offense, comics legend.) There are several interesting things happening in the work: Its independence from the DC Universe, the astounding visuals of Sekowsky, the ten years early introduction of the comic book "realism" of the 80s. But ultimately the whole event is the comic book industry equivalent of a husband unsure of what he did to piss off his wife.

Now, with (deep breath) DC Retroactive Wonder Woman: The 70s, O'Neil has a chance to tell an untold tale of Diana Prince the boutique owner/superspy, with versatile artist J. Bone intepreting into pen and ink. Alongside this shot at redemption, DC presents a backup story from the original "New Wonder Woman," for readers to compare. So judge for yourself, intelligent, well-informed readers who don't sling caps and insults for the sheer rush of blood pressure. Is Sekowsky and O'Neil's version of the character a feminist creation, or just another way we men take away women's power?

The more important question: Why does it matter as much as we think it does?

More From ComicsAlliance