Apocalypse Comics: The End Times Come on Wednesdays

When I was a kid, the apocalypse scared the crap out of me. Not in that long-term "I'd better be good" way like it's supposed to. I experienced genuine fear and horror at the possibility that the world would someday be thrust into Armageddon. Sunday School studies of The Books of Daniel and Revelation kept me awake at night, worried eyes pleading at the ceiling, fear engorged on images of seven-tailed serpents, blood-filled skies, and armies of undead rising from the grave. Lame, right?

When I was a kid, the apocalypse scared the crap out of me. Not in that long-term "I'd better be good" way like it's supposed to. I experienced genuine fear and horror at the possibility that the world would someday be thrust into Armageddon. Sunday School studies of The Books of Daniel and Revelation kept me awake at night, worried eyes pleading at the ceiling, fear engorged on images of seven-tailed serpents, blood-filled skies, and armies of undead rising from the grave. Lame, right?

Fortunately I grew up, learned a few interesting things known as "facts," and engineered a serious paradigm shift in my belief structure. My name is John, and I no longer fear the apocalypse. Don't even believe in it. I am, however, fascinated by it. The hole that was bored into me by anxiety has been filled with an appreciation for eschatology, and to this day I am easily drawn in by stories of the End Times, whether they are epic poems, ancient calendars that mysteriously end, or one-hundred-million-dollar movies that are pretty much guaranteed to drop IQ.

It's not just me. Since the anxious buildup and deflating reality of Y2K, revelation has been on the brain. As 2012 looms and the mystery of the Mayan calendar threatens to disappoint yet another wave of scorched Earth hopefuls, popular culture has become fixated on the disastrous possibilities. Don't believe me? Watch the History Channel for thirty seconds. Then call me back and apologize. For whatever reason, these stories are necessary. They are hard-wired into our brains; dug in to genetic memory like black, bulbous ticks; the benign tumor that keeps us going for checkups. They have appeared in nearly every culture, in every form of storytelling, like shadow versions of one another. And though the genre of apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic fiction has made its mark on comics, there remains ample territory for discovery.

Like so many other advancements in comics, apocalyptic fiction owes a lot to Jack Kirby. Though the subgenre had been popular in fiction since World War II, the subject remained largely unexplored in sequential art, other than the odd short story in "Strange Adventures" or other sci-fi rags. When the King defected to DC in the early 1970's, he unleashed the hyperkinetic pop bomb that is The Fourth World, including "Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth."

Years after a mysterious event known only as The Great Disaster (which turned out to be "Final Crisis"), man's status as dominant species has been upended by hordes of highly evolved beasts. Kamandi is one of only a few intelligent humans left, and with the teachings of his grandfather Buddy Blank (O.M.A.C.), and his friends Ben Boxer and Dr. Canus, seeks to return sentience to mankind.

"Kamandi" is the first long-form Western comic steeped in eschatology (if I'm wrong, enlighten me. I like being enlightened), and it effectively established the formula for all popular post-apocalyptic dramas: mysterious catastrophe, crazy new status quo, and the quest to survive/right the world. Despite the obvious parallels to "Planet of the Apes," "Kamandi" injected some very fresh energy into the comics medium, opening the door for dozens of comics focused on post-apocalyptic storytelling.

(Let's take a moment to differentiate between post-apocalyptic and dystopian. Though many comics take place in a crappy future, such as "Days of Future Past" or Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons's excellent "Give Me Liberty," there is no clear disaster or crisis point discernable as the cause of future crappiness, and no Campbellian post-destruction quest linked directly to the disaster's nexus. Thus, dystopian. Eat my logic.)

(Let's take a moment to differentiate between post-apocalyptic and dystopian. Though many comics take place in a crappy future, such as "Days of Future Past" or Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons's excellent "Give Me Liberty," there is no clear disaster or crisis point discernable as the cause of future crappiness, and no Campbellian post-destruction quest linked directly to the disaster's nexus. Thus, dystopian. Eat my logic.)

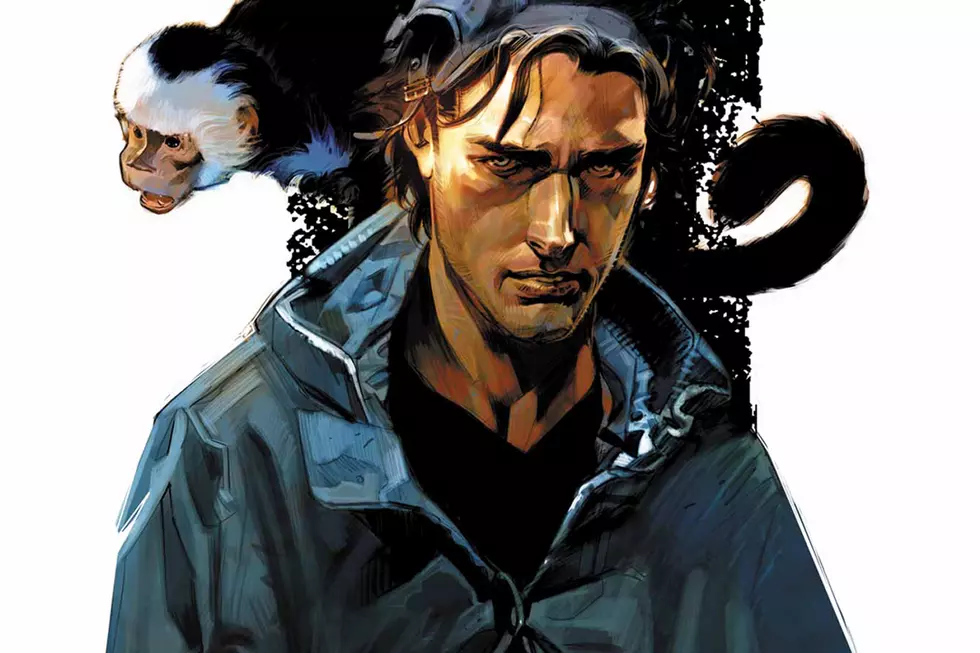

There have been a lot of very good comics that followed Kirby's template. A lot of bad ones, too, but let's try to remain positive. Over the last ten-plus years, apocalyptic comics have increased in both frequency and quality, with stellar, sub-genre-evolving efforts like Ed Brubaker and Warren Pleece's homage to romance comics, "Deadenders," Robert Kirkman's zombie opus "The Walking Dead," Brian K. Vaughan and Pia Guerra's magnificent "Y: The Last Man," and Antony Johnston's wonderfully-realized "Wasteland." (Jeff Lemire's "Sweet Tooth" may soon be added to this list, although it draws more from Cormac McCarthy's "The Road" and Harlan Ellison's "A Boy and His Dog" than the Kamandi heritage.)

Each of these works is worthy of its own entry in the post-apocalyptic apocrypha, finding fresh ways to work within what could be schlocky, obvious premises. In the stewardship of lesser creators, comic book apocalypses like The Big Wet, zombie uprisings, or the wiping away of every male on the planet could easily be lost in melodrama or plotting that thinks it's much cleverer than it actually is. With meticulous world-planning and slowly-unfolding mysteries, though, they've managed to keep the subgenre alive and thriving, proving that some unmapped territories remain even in the twenty-first century, when the post-apocalyptic story may be at its most relevant.

The most interesting studies of the apocalypse tend to come at the subject from different angles, far from the struggle for survival in a savage environment, or the quest for clarity in an unsure world. They focus on the dying man making a film, the heroes struggling to save the world from damnation, and even the possibility that the great revelation isn't such a bad thing after all -- a collection of practical oddballs, each dealing with End Times is significantly different ways.

If anyone tells you the eighties were a simpler time, hand them a copy of "When the Wind Blows." Then crush their collarbone with a mace.

While we're on the subject of ultra-violence, let's discuss "The Invisibles." And don't say it's not about the apocalypse. That'll getcha a quick fork in the eye. Grant Morrison's three volume smartbomb is essentially a treatise on the possibilities of a Gnostic apocalypse.

While we're on the subject of ultra-violence, let's discuss "The Invisibles." And don't say it's not about the apocalypse. That'll getcha a quick fork in the eye. Grant Morrison's three volume smartbomb is essentially a treatise on the possibilities of a Gnostic apocalypse.

Among the earliest Christians, the Gnostics set themselves apart from what was essentially a ragtag collection of doomsday cults by believing that what awaited man in the end times was not trial, but celebration. Including the Essenes, probable authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Gnostics believed that reality was just a veil covering higher levels of existence. Along those lines, they held that any apocalypse – literally "lifting the veil" in Greek – brought with it an apotheosis, and progression into a virtual garden of delights.

As Gaiman-McKean collaborations go, "Signal to Noise" is actually slightly underrated, typically thought of after other efforts like "Violent Cases" and "Mr. Punch," both of which deal with the author's memories. But "Signal to Noise" is hauntingly unique in the McGaiman catalog. As the filmmaker comes closer to his own end, his visions of the end that never came become more and more disturbing as the villagers abandon their homes and give in to hopelessness, all painfully rendered in McKean's bleak, stabbing blues.

As Gaiman-McKean collaborations go, "Signal to Noise" is actually slightly underrated, typically thought of after other efforts like "Violent Cases" and "Mr. Punch," both of which deal with the author's memories. But "Signal to Noise" is hauntingly unique in the McGaiman catalog. As the filmmaker comes closer to his own end, his visions of the end that never came become more and more disturbing as the villagers abandon their homes and give in to hopelessness, all painfully rendered in McKean's bleak, stabbing blues.

While not dealing with eschatology in a direct way, "Signal to Noise" wrestles with apocalyptic themes in the only way they truly matter. Fear of the apocalypse (such as the one experienced by a namby-pamby 11-year-old me) is nothing more than the fear of death dressed up in symbolism. This book stands as one of the most relevant of its decade, and a reminder that someone should pay McGaiman an obscene amount of money to make another graphic novel.

Of course there are many more books that touch on the apocalypse in different ways. We haven't even touched on many foreign interpretations like British books "Tank Girl" or "Judge Dredd," or manga efforts such as "Grey" or "Fist of the North Star." There's also a considerable amount of apocalyptic themes in mainstream superhero books, notably used by Mark Waid and Alex Ross in "Kingdom Come."

Eschatology is endemic to comics, and will continue to pop up in the medium in several ways: good or bad, clever or cliché, revelatory and frantic and bizarre in their own twists of style. It will be a part of the medium for as long as the art form survives, and as the comics above indicate, there remains ample room to stretch out.

Or at least until the sentient paperclip uprising of 2012.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Kamandi Skips The Con, But Still Has A Weird Time In San Diego In ‘The Kamandi Challenge’ #3 [Exclusive]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Kamandi00.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![An Epic Adventure Is Underway In ‘The Kamandi Challenge’ #1 [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/12/KACHA_Featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![DC Reveals Art And New Details For ‘Kamandi Challenge’ Tribute To Kirby [NYCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/10/Kamandi00.jpg?w=980&q=75)