The Artist’s Spider-Man: The Moody Atmosphere of Mike Zeck

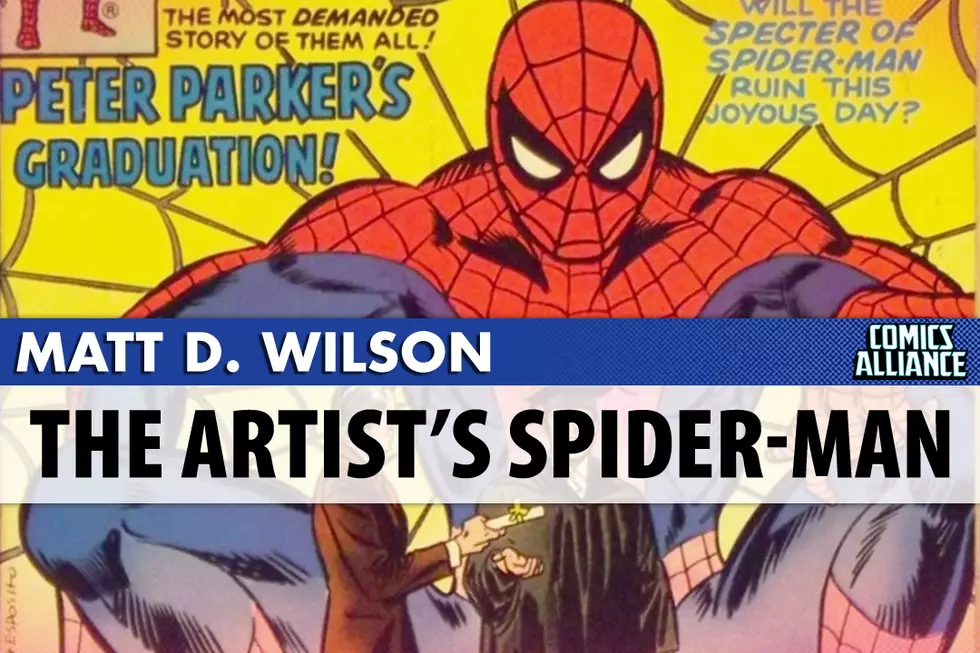

Like many other superheroes, the 1980s were the decade when Spider-Man went dark. In Spidey's case, it was a literal shift into darkness, as the new black costume, which Peter Parker got in 1984's Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars #8, by Jim Shooter and Mike Zeck, signaled a tone change in a character known for bright colors, soap opera drama and clever quips.

Zeck is among the artists spotlighted in this series who drew the fewest total Spider-Man comics, yet his work on the definitive dark 1980s story, "Kraven's Last Hunt," marks him as Spider-Man artist of note. Much of the imagery from that story shaped Spider-Man stories for much of the next three decades.

Following its debut (its first chronological in-story appearance was in Secret Wars #8, but Amazing Spider-Man #252 by writers Tom DeFalco and Roger Stern and artist Ron Frenz pre-dated its publication by several months), stories about the alien nature of the black costume and its effects on Peter's psyche --- many of them drawn by Frenz --- continued for about a year and half. Eventually, Peter got rid of the costume, revealed to be an alien symbiote, in Web of Spider-Man #1 by Louise Simonson and Greg Larocque.

Fans loved the costume, though, so Marvel's editors decided to keep it in the rotation. In-story, the Black Cat made Peter a cloth version he could wear, switching them off with his traditional red and blues. (Here's a good a place as any for this interesting side-note: A fan named Randy Schueller actually submitted the idea for a black Spider-Man costume to Marvel in 1982 as part of a talent search for aspiring writers and artists. Originally, the idea was that Spidey would get a black costume from Reed Richards that used the same unstable molecules that the Fantastic Four costumes did. Shooter, then editor-in-chief at Marvel, bought the idea from Schueller for $220.)

Stories that explored Spider-Man's darker side and his growing anger issues continued, too, almost as if to mirror the tone shift presaged by the costume. For example, writer Peter David and artist Rich Buckler's "The Death of Jean DeWolff," which ran in Peter Parker: The Spectacular Spider-Man in late 1985, ends with Spider-Man nearly killing the villain the Sin-Eater.

That was all really preamble to "Kraven's Last Hunt," though.

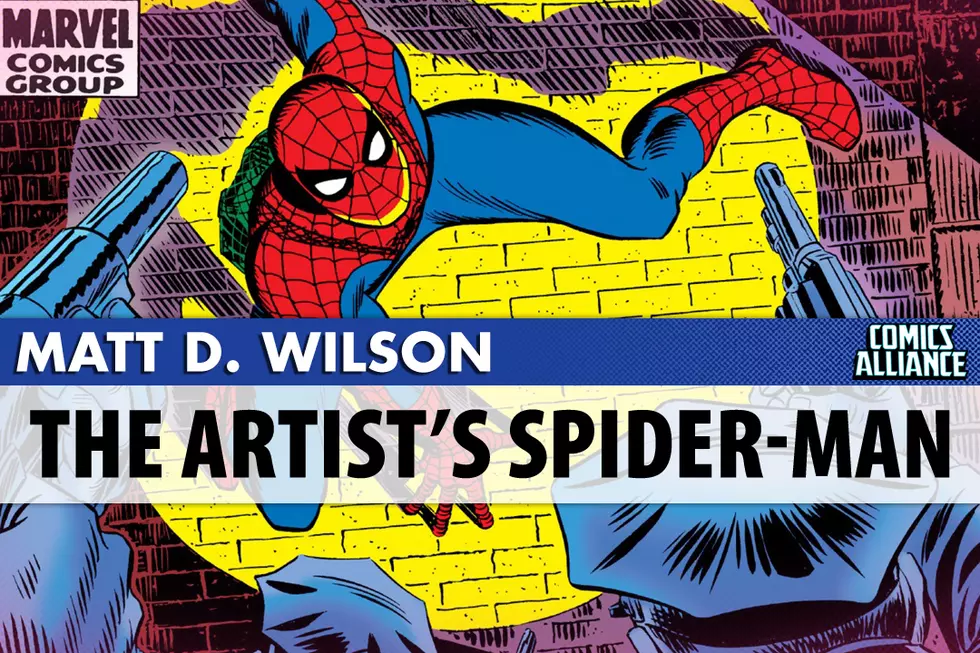

Unlike "Death of Jean DeWollff," the story by Zeck and writer J.M. DeMatteis doesn't focus on the dark side of Peter Parker, instead it puts a villain, namely Kraven the Hunter, inside Spider-Man's costume. Zeck makes it abundantly clear throughout Kraven's time in the suit that this is not the Spider-Man readers know. It's all there in the body language, the posture and the body shape. This Spider-Man carries an ominousness that wasn't there before.

Here's how DeMatteis described Zeck's work on the story in an interview with Back Issue:

Because Mike nailed the plot elements so perfectly in his pencils—every action, every emotion, was there, clear as a bell—I didn’t have to worry about belaboring those elements in the captions or dialogue. I was free to do those interior monologues that were so important to the story. If any other artist had drawn “Kraven’s Last Hunt” ... it wouldn’t have been the same story.

And then there's the subject matter: dissociative mental states, obsession, the apparent death of Peter Parker (it turns out he was just tranquilized), being buried alive, and Kraven's eventual suicide. There's a lot of death hovering around in "Kraven's Last Hunt," and Zeck takes the opportunity to include a lot of almost gothic horror imagery, something that hadn't really been part of Spider-Man aside from a few Morbius appearances. This wasn't just a variation on classic superhero art. Zeck was doing something very new, and much moodier than readers had seen in a Spider-Man story before.

That imagery becomes even more pronounced in Zeck and DeMatteis' 1992 sequel to the story, "Soul of the Hunter," in which the spirit of Kraven battles Spider-Man in a graveyard. It was the addition of another genre on top of the superhero/romance/comedy/family drama mishmash Spider-Man had already long been. Death has always been a part of the Spider-Man mythos --- after all, Spider-Man's story begins with Uncle Ben's death, and Gwen Stacy's death is one of the most important moments in the character's history --- but "Kraven's Last Hunt" confronted it in a way that no other creators had. There's a reason why so many spiritual and direct sequels to the story --- most recently "Grim Hunt" --- have popped up in the decades since.

Yet in with all the darkness, Zeck maintained Peter's humanity and depicted his relationship with Mary Jane very warmly.

That's the hallmark of great horror, isn't it? The contrast between the terrifying, bone-chilling moments and the moments of humanity, the ones where the audience can connect with a character.

Perhaps that's what set Zeck's work apart, aside from gorgeous detail and brilliant character work. He didn't just wallow in the darkness. He could bring in the light, too.

More From ComicsAlliance