![Bruce Wayne Wages ‘Jihad’ In 1991’s ‘Batman: Holy Terror’ [Review]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2011/09/batmanholyterrorcover.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Bruce Wayne Wages ‘Jihad’ In 1991’s ‘Batman: Holy Terror’ [Review]

Frank Miller's Holy Terror, Batman! goes on sale this week after a long and strange journey from initial concept to finished graphic novel. When first imagined, the book was a story of Batman fighting Al-Qaeda titled Holy Terror, Batman!, as a nod to Robin's catchphrase exclamations from the late '60s television series. As you probably know, ComicsAlliance's David Brothers has written an essential review of the Miller book. But what you may not know is that those three words, "Holy Terror, Batman," in a different order, have been the title of another Batman story before.

Back in 1991, DC Comics published a prestige format one-shot called Batman: Holy Terror. The book was written by Alan Brennert with art by Norm Breyfogle and colors by Lovern Kindzierski. As part of the publisher's then-popular Elseworlds line, the story was set in an alternate history United States that had been established and governed for centuries as a Protestant Christian theocracy, one that had twisted its philosophy into an extremist and oppressive regime.Over 20 years later, Batman: Holy Terror is still relevant for addressing the concerns of a state strictly enforcing religious beliefs as law, as well for its careful handling of the distinction between a religious faith and those who corrupt it as a means to control others. Indeed, the book remains an enjoyable one-and-done 40-page story with great artwork. Batman: Holy Terror is of course out of print but can still be found in back-issue boxes at comics shops and from the usual internet retailers. Spoiler warnings don't usually apply to 20 year-old comics, but there you go just the same.

For those of you unfamiliar with DC's old Elseworlds line, it was a series of standalone books and occasionally miniseries that took place in a wide variety of alternate history or alternatue future DC Universes. In some cases, a character's singular destiny was changed (like Bruce Wayne receiving a Green Lantern ring instead of Hal Jordan). In others, superheroes existed in different time periods, like Batman as an agent of President Lincoln.

In the world of Batman: Holy Terror, English Protestant leader Oliver Cromwell survived the fatal case of malaria that actually killed him in 1658 and lived another ten years. As put forth in the book, that extra decade meant Cromwell's revolution and its devoutly Protestant beliefs were never swept away after his death, and served to create a similar system of beliefs and, along with them, a complete absence of the separation of church and state in America. Flash forward to late 20th century in Gotham Towne, where Thomas Wayne, the Personal Physician to some of the country's highest political leaders, is killed in a mugging along with his wife Martha. Their son Bruce is left an orphan, and Gotham Inquisitor Jim Gordon is left to frustratedly furrow his brow under a curly white wig when his efforts to further investigate the case are blocked.

Years later Bruce Wayne is a grown man who's turned down an opportunity to join Lord Commissioner Gordon as an Inquisitor. Instead, Bruce has chosen to become a Reverend. On the eve of his ordination, Gordon pays Bruce a visit and reveals a shocking secret: Bruce's parents weren't killed in a random crime, they were executed as enemies of the state. Thomas Wayne had been running an underground clinic to help people who had been cast off by the state. Among them, homosexuals subjected to burns and shocks as part of a government-run behavior modification programs, and women who had attempted to dangerously end their own pregnancies because of the unavailability of safe and legal abortion. The Waynes were too prominent to be publicly tried, so their crimes were hushed up and their punishment made to look like an unrelated incident.

The revelation crushes Bruce, who had seen the church as a way to find meaning after the loss of his family. At the same time, the news ennobles Thomas Wayne as someone who's not merely a good man willing to use his power to help the less fortunate, but a man willing to risk his very life to help lessen the suffering of others. Bruce finds an old demon costume his father used to wear in a church passion play and decides to use it as a disguise in his quest to find who was directly responsible for his parents' death. Thus, the Batman is born.

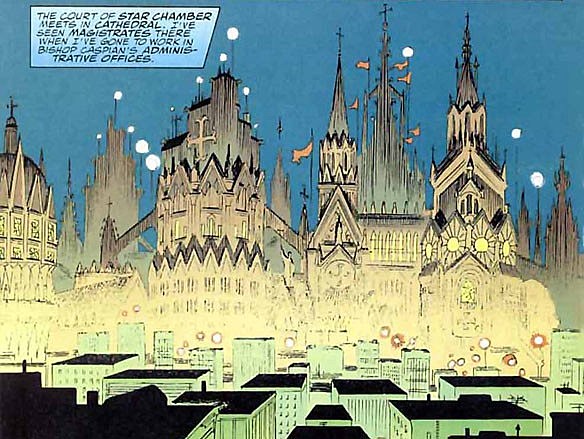

The investigation leads Bruce to Gotham's main cathedral. Breyfogle and Kindzierski's art in Holy Terror is very good, if somewhat dated by a modern audience's standards, but where it's most impressive is in depictions of the massive scale of church architecture in Gotham Towne. Religious buildings tower over the people and impress them into obedience. At the same time, this version of the city still feels like the Gotham we know, just a Gotham whose skyscrapers and gargoyles have been replaced with crosses and spires.

Holy Terror gives in to one of the regular problems of the Elseworlds line and decides that if it's going to show an alternate version of the DC Universe, then it's going to cram in as many alternate versions of DC characters as it possibly can. The religious police state has been capturing and studying anyone with superhuman powers in order to give similar abilities to those fighting the worldwide crusade to spread the faith. Amusingly, this crusade is led by General Oliver North, which is a reference some of you are too young to get, which makes me feel very old (and some of you probably guessed he's an old DC character that doesn't get used anymore, and that makes me feel worse). Bruce's quest for justice suddenly turns into a rescue mission to help familiar faces like Barry Allen aka The Flash and Arthur Curry aka Aquaman. Batman's efforts are opposed by fanatical religious convert Zatanna, Clayface and the program's director Saul Erdel. Erdel has escaped the official state persecution of Jews by providing a service that's useful to the country's elite. He takes a sadistic joy in what he does, turning Barry Allen's power against him in a way that causes Barry to burst into flames (and Bruce to weep openly about a man he only met a half-hour ago).

Erdel's worst crime, however, is the study, killing and dissection of a a man turned over to the state after he was found as a baby in a field by "a God-fearing couple in Kansas." And although most of the superhero cameos in Batman: Holy Terror don't add much to the plot, Bruce being shown the body of the man who should have been Superman, in a pose with blatantly obvious symbolism, is a powerful moment by Brennert, Breyfogle and Kindzierski.

The Superman scene inspires Bruce to never give up, and he fights back until Erdel inadvertently kills himself when a bullet from his gun ricochets back off Superman's body and hits him in the chest. So even though the two never met while both were alive, Batman: Holy Terror's world still sees Superman and Batman working together to fight evil.

Bruce finally comes to the Star Chamber, the secret court that ordered his parents' execution, intent on revenge. But the truth he finds there isn't to his liking. The Star Chamber acts by having its twelve members vote entirely by secret ballot, with no records of the decisions kept. Bruce can never know who ordered his parents killed. But at the same time he realizes it's the system that's at fault, for it allowed such a court to hold power in the first place. If he wants to see justice done for his parents, Batman must dedicate his life to bringing this system down.

Batman vows to continue his fight as a masked vigilante by night, but remain Reverend Bruce Wayne by day. As much as the corrupt state and its abuses of the church's religion offends him, Bruce still believes strongly in his own faith. He claims that "Defiance of Gods' self-styled interpreters is not denial of God." The teachings of the Bible that helped this Bruce Wayne come to terms with the death of his parents and seek to help the less fortunate are not something he's ready to throw away because others have used the same holy book as justification for horrible acts. Bruce stills sees it as doing God's work to preach during the day and fight a corrupt system by night, a campaign that Bruce himself even refers to as a "jihad," borrowing the Arabic word for a religious struggle (either military or spiritual) whose use has become so intensified in the years since this comic's release.

The title has uncomfortable implications in today's post-9/11 world, but Brennert, Breyfogle and Kindzierski's Batman: Holy Terror is in many ways is less outdated in its confrontation of the issues of corrupted faith and violence now, 20 years after it was published, than Frank Miller's Holy Terror is in the first week of its release. Religious outcasts like those Thomas Wayne sacrificed his life to protect are still discriminated against across the world, and Batman's resolve to exemplify the best traditions of his faith, even in a world where men can and do perform terrible actions in that faith's name, is a powerful idea that has taken on new relevance in the world of today.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Superknights and Batmancers: The Best Fantasy-Inspired Superhero Art Ever [Fantasy Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/10/fantasy_featured.png?w=980&q=75)