I’m David: Writing While Black and ‘One-Punch Man’

It's weird being black sometimes. People have expectations that they just assume are true, you know? People at parties want to discuss race relations and Obama all the time for some reason, your non-black friends will grade your blackness, people want to touch your hair, and worse. There are all these little things that don't mean much on their own, but taken together, it paints a pretty decent picture of how Americans approach race. White is treated as the default experience, and being black, Japanese, gay, or anything else but straight and white is a Special Experience, one that needs explanation. It's true in comics, too. A lot of fans -- not all, but enough to be loud on the internet -- expect black writers to be angry revolutionaries first and writers second, and treat them accordingly, regardless of the story the writer actually put down on the page.

I'm David, and I want to talk to you about a phenomenon we're gonna call writing while black. It's a downer, but we're also going to talk about a funny comic called One-Punch Man, courtesy of Yusuke Murata and ONE, so stick with me.Let's mix things up a bit, because I got a good question that I couldn't boil down to around two hundred words.

Alex Price asked: Will you be addressing internet "Black Supremacist" criticism of writers like [Dwayne] McDuffie and [Reginald] Hudlin when on [Black Panther]?

What Alex is referring to here is something I'm going to call "writing while black," because I honestly don't know if there's a proper term for it yet. In short, there's a tendency for a certain subset of comics fans to view books written by black writers with a suspicious eye. The motivations of the writers come into question. Sometimes that suspicion manifests itself as viewing a book as a "black book" instead of a regular old comic book. Other times, it's a kind of defensive, twisted white guilt, like when fans declared that Black Panther and Storm were only getting married because they're black, and how offensive that is. (They didn't. It's not.) And other times, it's just straight up racism, of course.

The specific thing that Alex is getting at, though, are the times when fans look at a book written by a black writer that feature a black character winning at something (or even being present, which I suppose is a type of win in and of itself) and go, "Hmmm... I dunno about all this. This seems pretty anti-white/preachy/political/angry/etc." The accusations tend to reveal more about the complainer than the complained, in my experience. Nine times out of ten, it isn't what they say it is.

I've got a couple particularly horrendous examples. Walk with me for a little bit here before you hit the comment box.

Reginald Hudlin wrote Black Panther: Who Is The Black Panther?, which included a scene where a prior incarnation of the Black Panther beat Captain America in a fight. The book features a very cool John Romita Jr-drawn spread of the fight, but a lot of fans didn't take it well. It was seen as an insult to Cap, because how could anyone, especially some black dude, ever beat up Captain America? I mean, this is a guy who regularly fights a French dude whose only power is jumping well and another guy whose entire gimmick is that he's a regular Nazi dude with a skull for a face, and Black Panther gives him trouble?

In the eyes of fans, Hudlin had the Panther beat Cap as some type of get-back for... something (I honestly don't know what) or as an indicator of his black supremacist views. The fact that racist white characters -- not a lot, but a few -- showed up in the book was another sign that Hudlin was on his soapbox. It was unfair that white people were being treated like bad guys while the black guys got to win.

If you think of the history of cape comics, of how often generic black or latino muggers/rapists show up in alleys in basically everything ever, the irony may kill you. I should have warned you beforehand. Sorry.

But the scene wasn't a get-back. It wasn't a soapbox. It was simply a story where one character won over another in his own comic and other characters said stupid things before being admonished by other, smarter characters. It wasn't a statement or a line drawn in the sand. Who Is The Black Panther? is just like every cape comic ever, but this time, the lead was black and the primary villain was white.

These accusations are often couched in rhetoric that includes the utterly fake and obnoxious term "reverse racism." Sometimes people express concern that the author is using his soapbox in an untoward manner, which usually means "I don't think this person agrees with me politically and I wish they'd stop it." For a good example, check out the letters page of Black Panther #4, where Reggie Hudlin answers a letter writer's question on the subject. It's too long to excerpt in full here (you can read the entire thing over here), but here's a choice quote:

Regarding your assertion that the whole story was saying "all black people are good, all white people are bad," all I can say is, this remark says more about you than the comic I wrote. Aren't the first "bad guys" in the book black invaders with body part trophies from previous raids? If you think I'm vilifying the administration, isn't that a black woman in charge? Clearly, all black people aren't "good" in this issue. So maybe the problem, in your eyes, is that there aren't enough "good" white people? Why? Captain America may have lost the fight with the Panther, but he certainly doesn't say or do anything to betray the principles he stands for. And when one guy in the meeting says something stupid, everyone looks at him like the fool he is, and once he is dragged away, intelligent conversation resumes -- so why brand the entire room as racist because of one guy's comments? I wouldn't presume that about them, so why would you?

People suspecting creators of writing while black is much, much more common than you might expect, and it's never pretty. Dwayne McDuffie got it bad, particularly when he was working on Justice League of America for DC Comics. Here's a couple of choice quotes from fans, from a now-deleted preview of Justice League of America #34 that ran on Newsarama:

"...how many blacks did McDuffie manage to sneak onto the team this time–five? (I bet DC editorial gave him the same order as Burger King in that lawsuit–to "lighten things up around here.")"

"Couldn't they get Static, Black Lightning, or one of his daughters instead of Dr. Light on the cover of BET League of America? Ha!"

"Maybe they should establish a separate league for all the negro superheroes. I'm not saying kick them ALL off. One would be okay. (Doesn't Hollywood have some kind of law that says every movie has to have at least one black in it?) I just think they're going overboard with all this diversity stuff. I mean, how many comics do minorities read anyway?"

There's no exaggeration here. No edits, no jokes. No photoshops. These comments are real. I found them when they were quoted by McDuffie himself in 2009, and they really struck me as being vile in a way I didn't expect to see in public. Some comics fans are very, very interested in pointing out when writers are "blackifying" (not my word, though I cherish it) comics.

It comes from the thing I mentioned earlier, when people look at books featuring black characters or black creators working on black characters as a "black book." That sets up certain expectations, for better or for worse. When a black writer comes onto a book and suddenly the black cast doubles -- or goes from zero to one -- some fans cry black supremacy. 'Cause what else would a black dude do when he gets on a book, other than "urbanize" everything? Being black is different from being white, the logic appears to go, so obviously they won't write comics like we do. We like normal comics -- they like black ones. (It goes without saying that being black is different from being white, but near as I can tell, we all like the same types of stories, right? Just so we're clear.)

Here's the thing, though: McDuffie was, in fact, writing Justice League of America when several black members were added to the cast. Sometimes they talked to each other. Sometimes they talked about being black. But here's the rub: adding Black Lightning, Firestorm, and John Stewart to the cast wasn't McDuffie's idea. DC editorial, in addition to getting him to tie into other stories and shuffling the cast on a whim and telling him at the last minute a few times, wanted to diversify their cast. As a result, McDuffie was simply the hired gun in charge of making sure that the stories were good. (They were, though the art left a whole lot to be desired for most of his run.)

But from the perspective of the fans, McDuffie is the guy driving the boat, and he gets the blame. The fact that he's black is only icing on the cake. It's an explanation for what you perceive to be an injustice, an excuse for why a writer was allowed to transgress against the natural order of which superhero can beat up another or how many brown faces a team has to have before it needs a BET or Univision sponsorship.

Alex asked if I'm going to be addressing the "writing while black" criticisms. Despite what the thirteen hundred words before this sentence suggest, I don't know how to address it. I could talk about how it makes me feel like an unwanted stranger in my own hobby. I could talk about how it poisons the conversation and sucks the air out of the room. I could talk about how it ties into American culture, where black things are black and white things are merely normal. I could talk about how mad it makes me when I see it, every single time, and how impotent that anger feels. But we've had that conversation before. We're always having that conversation. I'm tired of that conversation.

Instead, I'm just going to point it out. This happens. You cannot deny that it happens. It happened yesterday and it'll happen tomorrow. (It'd happen today, but good luck finding a black writer at the Big Two. Win some, lose some.) Some people (idiots, let's call them idiots) are going to read this and think that I'm saying that any criticism of black writers or black characters is verboten. Some people are going to think I hate white people.

That's cool with me. I'm not talking to them. I'm talking to you, the person reading this who just went, "Oh. OH." and started looking inside their hearts a little bit. I'm talking to the person who is looking to learn, the person who may be guilty but doesn't realize it, or maybe just the person who was looking for a something good to read on their lunch break. I'm not preaching to the choir, but I definitely want to connect with that person who might join the choir in the future and ask them these questions:

Why is it cool and natural for Kitty Pryde to have a romance with Iceman but Storm and Black Panther are apparently an "only because they're black" relationship?

Why is it cool for Uncanny Avengers to launch with an exclusively white team, but if you add three black men to the Justice League -- all three being characters or concepts with a history of serving with the JLA over their forty-some years of existence -- some fans treat it like they just walked into a Mau Mau rebellion?

This column is inverted, on account of my utter inability to run short lately. So, in lieu of our usual Q&A, here's a few quick thoughts on a recent comic debut that's currently impressing me: ONE and Yusuke Murata's One-Punch Man.

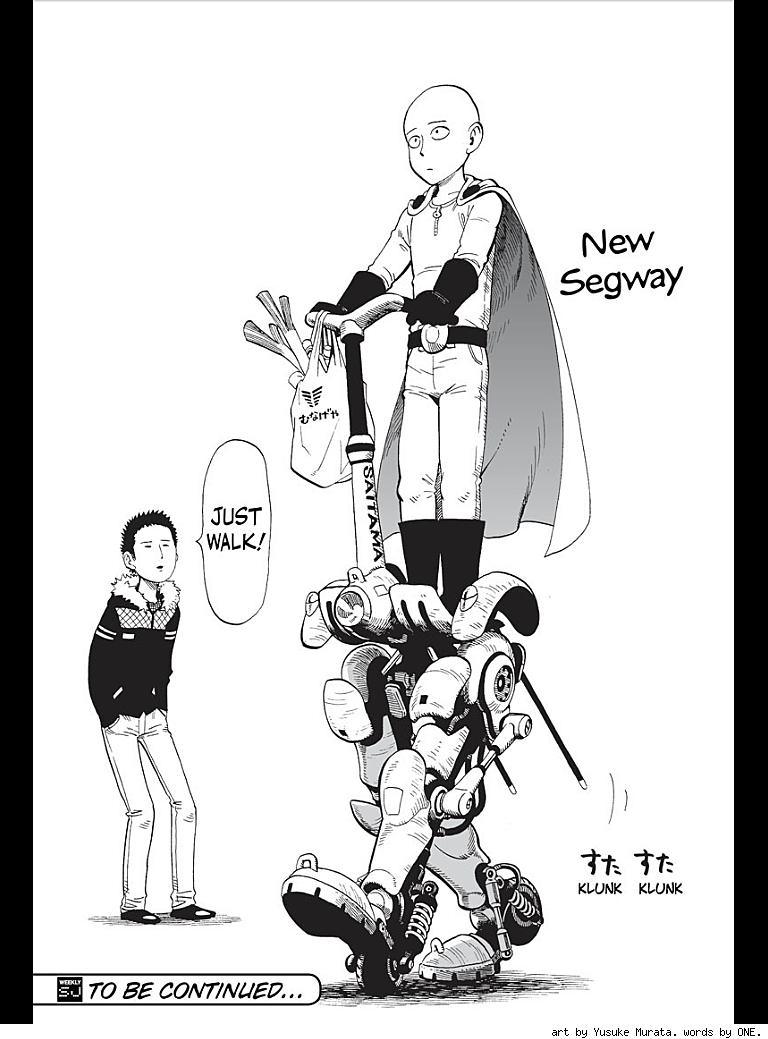

One-Punch Man is a gag comic about a superhero named Saitama who has managed to train himself to the point that he defeats every single bad guy he meets with a single punch. He's the ultimate protector, but there's just one problem: Saitama's bored. He wants excitement, he wants action, but all he ever gets is one punch and then a lonely walk home. He daydreams about alien invasions. He fantasizes about having trouble during a battle. He loves the idea of being in a real pinch and fighting his way out of it. But when the chips are down and things are serious... one punch is all it ever takes.

ONE and Murata are telling a story that wouldn't be out of place in any adventure comic, but that one twist turns it from a fun adventure comic into a funny adventure comic. It's goofy and dumb in all the right ways. It's running in Weekly Shonen Jump on Vizmanga.com, and believe you me: you want it.

If you have a question, let me know by leaving a comment or hitting me on Twitter @hermanos. Let's talk comics, movies, music, video games... anything goes.

More From ComicsAlliance