Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso Create A Bleak And Plausible Future In ‘Spaceman’

The creative team of writer Brian Azzarello and artist Eduardo Risso shouldn't just be well-known by now, it should be feared and respected. After first meeting on Vertigo's Jonny Double miniseries back in 1998, the pair have been regularly collaborating ever since. In 1999 they worked together again on the stylist noir conspiracy thriller 100 Bullets, which clocked-in at one hundred issues and nabbed a slew of Eisner and Harvey awards for the pair. Even after ten years of working together, they apparently still hadn't had enough, and went on to create a few critically-acclaimed Batman comics, for DC's Flashpoint event and the Wednesday Comics weekly. They collaborated once again in late 2011 for DC Vertigo's Spaceman, which is collected in deluxe hardcover this week. And though the duo have made their names in the world of noir, Spaceman is an entirely different type of monster.

It's getting a lot harder to discern which science fiction is "post-apocalyptic," or "dystopian," and which science fiction is probably what's just going to happen. If a story takes place on a world that's teetering on the brink of total devastation, yes, it's apocalyptic. If a story is based in a future where an agency exerts control over people's lives - yep, it's dystopian. But if a story is set in a time and place where ecological devastation has destroyed entire cities, the gap between the rich and the poor is wider than ever before, and reality television stars probably have more power than some countries, that's just good, probably prophetic world-building that just predicts how much life is going to suck in the future. Instead of calling Spaceman "post-apocalyptic" or "dystopian" science fiction, we should just classify it as "stuff you should get ready for" science fiction.

The titular hero of Spaceman is Orson, a hulking, ape-like humanoid who is just trying to be a good man. Genetically engineered to terra-form Mars, Orson and several other "spacemen" were bred with bigger frames and thicker skin, denser bones and more muscle mass, all of which is realistically needed for longer space exploration. As much as George W. Bush pretended to like the idea of a manned mission Mars, we're realistically still pretty far away. Over an extended period in zero gravity, the human body breaks down: muscles atrophy, blood volume drops, and bone density decreases at a rate of 1-to-2% every month. When Azzarello heard about this real-world limitation to space travel, he came up with an interesting solution: genetic modification. Unfortunately, in his own estimation, it will probably cause a religious uproar and help bankrupt the nation.

The world of Spaceman is pretty bleak. Global warming has led to a rise in sea level, neatly dividing the one from the ninety-nine. The majority of the population - Orson included - live in The Rise, the submerged remnants of the country, and they're all about as poor as that kid from school who never took baths. The rich have all absconded to The Dries, which are exactly what they sound like: anything not destroyed by environmental collapse, protected against the rabble of The Rise with security forces and a retaining wall bigger than God. It's good world-building, but of course Azzarello gives it a twist: dwellers of The Dries still need people to clean their houses, so of course they mostly employ denizens of The Rise. It's a clever socio-economic situation that adds depth and structure to the story while seeming entirely plausible.

The relationship between The Rise and The Dries, the haves and have-nots, is a major theme of the book, and Azzarello provides several fascinating, insightful twists throughout. Yes, I will provide an example! In the world of Spaceman the most popular television show in is The Ark, a "realtee cast" about a Brad-and-Angelina-like couple who hold season-long competitions to determine the next orphan of The Rise they will adopt. You have to laugh, but nervously, and only for a second, since it feels like this could start happening tomorrow.

In Spaceman, Azzarello creates a world by simply extending current trends to logical conclusions. He even applies this formula to language - the cool slang, clever turns, and double entendres remain, but almost all the dialogue is written in a bizarre text-message-based grammar that's absolutely brilliant. "We? No--I work lone." "Not nomo. You want to hide her-- when you can't hide yersef?" "I braind I was doon okee." "Okee fokee you! All bodies kno--you a spaceman." People don't even laugh anymore - they actually say "LOL LOL LOL!" It may take a little work at first, but the astute reader's attention is rewarded with speech that is funny and entertaining, but still able to convey all the venom and threats you'd expect an Azzarello script to contain.

The world of Spaceman is not only logical, it's plausible, and the pair display their prodigious talents for great science fiction throughout. Of course, Spaceman also tells an addictive crime story, one involving kidnapped celebrities, meddling e-hookers, drug-dealing street urchins, and flashbacks to Orson and brothers' mission on Mars. It's an engaging morality tale acted out in a world where mankind continues its daily drudgery amid catastrophe, and visually, it's ravishing from cover the cover.

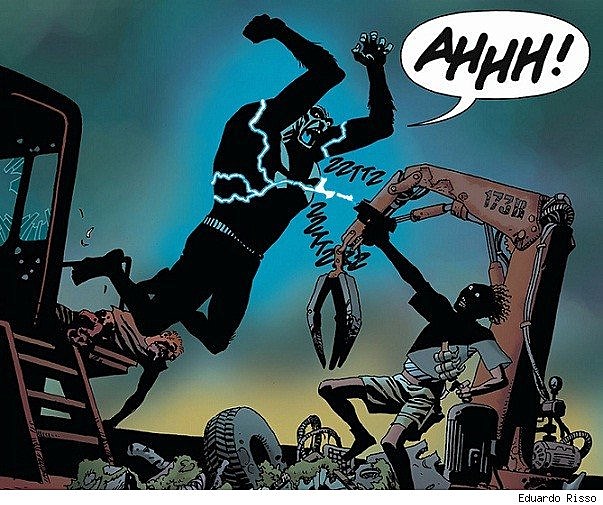

Artist Eduardo Risso is a gargantuan talent with the dynamic range to go from scenes of abject terror to moments of touching sincerity. His quirky, cultured, and impossibly thin pen lines make every panel a living scene, and even though almost everything in the future is garbage, it's still beautiful garbage. His page choreography and use of foreground and shading compliment an uncanny knack for visually distinctive characters that go from sexy to scary to goofy and everything else in between -- it's practically animation. Of course, that doesn't stop Patricia Mulvihill's coloring from stealing the show occasionally. At her best, which she is at for Spaceman, her colors don't just paint the scene, they convey perfectly-crystallized moments. And even though Dave Johnson's covers may not be collected in the HC (who can ever tell?), his work on Spaceman represents some of the best of his prodigious career.

Spaceman has everything: a likable hero, a unique world, social commentary, apes in space, wiseacre kids, and a working prediction for how awful your life is going to be someday. At the very least, you should read it just so you're a little more prepared.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Heroes Hit Hard In ‘DKIII’ #6 [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/09/DKTMR_6_featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![The Emerald Knight Returns in ‘Dark Knight Universe Presents: Green Lantern’ [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/01/dkgl_featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)