Magic Omnibus: Embracing The Radical Weird In Grant Morrison’s ‘Doom Patrol’

While at Comic Con, Grant Morrison dropped several enigmatic hints and subliminal messages to ComicsAlliance about his next mega-event, Multiversity, broke down the divisions between fictional universes, and even proclaimed that he thinks that he's made the world's first real superhero. He says things like that. Some people like him, many love him, and some people straight up hate him. With Multiversity starting up in August, you can be sure that there will soon be legions of detractors proclaiming that Morrison is the most overrated writer in comics, and nothing he's ever done has ever made any sense.

The release of DC's Doom Patrol Omnibus finally equips us to give these people the bludgeoning they deserve. (Metaphorical bludgeoning. ComicsAlliance does not condone actual bludgeoning.)

Conceived in 1963 by Arnold Drake and Bruno Premiani, the Doom Patrol were a collection of accident victims transformed into superheroes whose powers and appearance alienated them from a society they fought to protect. Like Marvel's X-Men, the Doom Patrol struggled with disenfranchisement, self-worth, and living with a gift that is also a curse. In fact, in their original incarnations, the franchises are so similar that one has to wonder at the circumstances of their nearly-concurrent creation.

Debuting just a few months before The Uncanny X-Men, the Doom Patrol had a wheelchair-bound mentor and were advertised as, "The World's Strangest Heroes!" The X-Men obviously featured their own physically-disabled but mentally acute leader, and were billed, "The Strangest Super-Heroes Of All!" because that's just clearly better. The X-Men's foils were The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, while the Doom Patrol fought The Brotherhood of Evil, and both teams of villains debuted in the same publication month, March 1964.

Drake has always contested that somebody in DC must have leaked the ideas to Stan Lee, but I prefer to believe that Drake and Lee simultaneously felt the undercurrent of the burgeoning civil rights movement, and subconsciously and independently imbued their creations with similar messages of support without actually using any black people.

Despite the big similarities -- including having the two coolest team names in comics history -- there are gargantuan differences between the two. Even though the mutants of The X-Men were outsiders and freaks, they were young, cool, sexy teenage freaks. They appealed to an exploding youth culture easier more easily than the traumatized members of Doom Patrol.

The Doom Patrol weren't kids in sunglasses and mini-skirts; they dealt with body horror, disability, and loss of humanity, and fought a super-intelligent gorilla and a brain in a jar. As awesome as that sounds, they never caught on like their mutant cousins, and while the X-Men are now part of the zeitgeist, Doom Patrol has been canceled more times than my annual physical. They were just too weird.

Apparently, Grant Morrison took that as a challenge to get even weirder. When Morrison and Richard Case took over Doom Patrol in 1989, they captured the essence of the original creation and re-synthesized it into a quirky, heartfelt, and modern interpretation that perfected its original intent.

One of Morrison's greatest assets is his ability to distil concepts into statements -- to take others' creations and decades of continuity, analyze them within their broader cultural contexts, and modernize and magnify the core idea -- and Doom Patrol is the first book where he truly displays that skill, turning the team into "The World's Strangest Heroes" once again.

With the assistance of exiting writer Paul Kupperberg, the book's roster was re-tooled into a lineup that redefined the outsider hero for the modern age. Classic member Cliff Steele, aka Robotman, remained in place, fashioned into an explicit metaphor for the trials of the physically disabled. A car crash survivor whose brain was implanted into an insensate metal body, Cliff is kept alive but unable to live.

As a result of childhood trauma, new member Crazy Jane is mentally ill, with 64 distinct personalities, each with their own superpowers. Although unstable and a burden on those she loves, she's actually the most capable member of the team when it came to confronting insane threats.

Negative Man was recalibrated into Rebis, a combination of the Negative Spirit, white male Larry Trainor, and black woman Dr. Eleanor Poole; Rebis is hermaphroditic, and mates with "hirself." Dorothy Spinner is a physically-deformed girl shunned by society who makes her imaginary friends come to life. In a very subtle statement on race (for such an over-the-top comic), retired member Joshua Clay, an African American, is the stable, socially-accepted presence in the team -- especially compared to Danny the Street, a teleporting boulevard with the affect of a male transvestite stage performer.

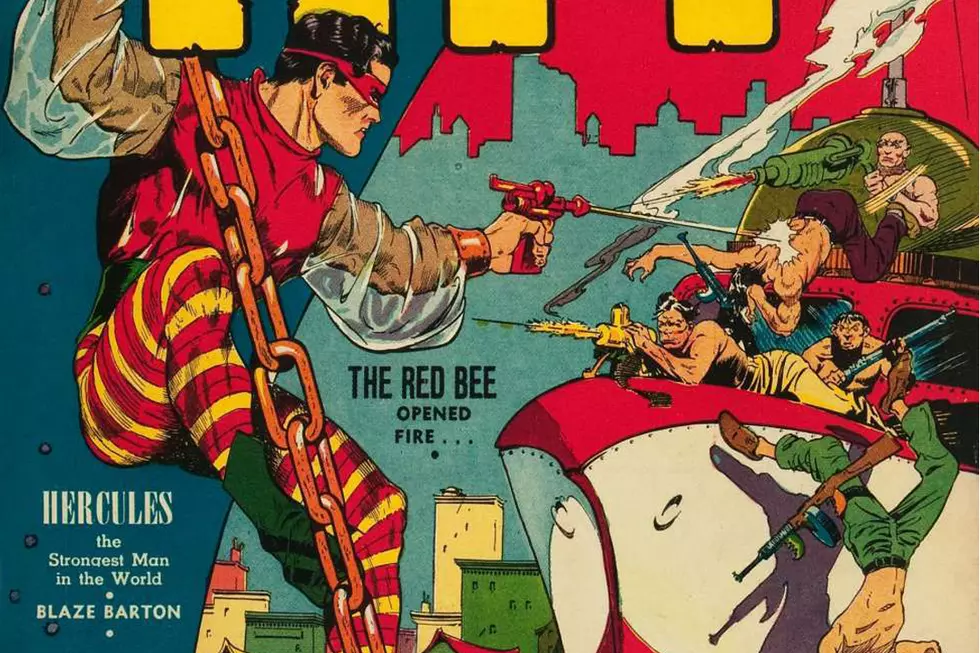

Comics have long made use of the outcast-as-hero trope, whether in the form of aliens, nerds, or the genetically different, and nascent themes of the struggles of the disenfranchised can be spotted all the way back into the Golden Age.

In Morrison and Case’s Doom Patrol, that message was broadcast proudly and specifically for the modern age, without ever assuming a didactic tenor. Typically, the theme of outsider-ism was expressed by the outcast fighting for the acceptance of the mainstream: freaks pining for normality, teenagers who would trade their gifts for the privileges of anonymity.

In Doom Patrol, the outcasts didn't want to assimilate, or to prove their worth by propping up the established order. While they began as guardians of the establishment, the Doom Patrol evolved to fight for their own interests and stand up for the outcast against the prevailing order. They no longer yearned to be like everybody else; they would change the world to be a better one for themselves. Physically challenged, mentally unwell, sexually “deviant,” and freakishly weird, they challenged society’s behaviors and readers’ ideas of normalcy.

That challenge extends to the storytelling as well. Animal Man quickly proved Morrison's predilection for experimentation in "The Coyote Gospel," but Doom Patrol was the first book that showed just how deep into the maelstrom he could go. It's as if The Beatles went from Rubber Soul to Sgt. Pepper without Revolver. (Actually, Morrison started Doom Patrol a little while after Animal Man and wrote both titles concurrently for years, so it's like The Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper while they were still finishing Rubber Soul.)

Like Jim Steranko in the 60s, Morrison infused the "low art" of comics with "high art" concepts, altering the schema of superheroes with Borgesian post-modernism, Burroughs cut-ups, and the humor, randomness, and the central idea of Dada: not everything has to be understood.

As the artist for the majority of the run, Richard Case became the perfect steward for such oddball material. At first, Case's style is blandly traditional, and even a little underwhelming by the standards of "blandly traditional," if I'm being perfectly honest. As the book went on and became increasingly strange, better, and more off-center, so did Case. He developed more expressive figures, put more emphasis into his cartooning, and played with panel perspective and page design. He understood the artistic influences that Morrison brought to the table, and incorporated mixed media and collage to make Doom Patrol actually look like a Dadaist artifact.

Though several very good artists filled in for Case -- including Sean Phillips, Jamie Hewlett, and Philip Bond -- and the covers were supplied by the likes of Simon Bisley and (in the trade collections) Brian Bolland -- it's still Case's look that comes to mind when you think of Doom Patrol. His goofy, unrestrained style made a great match with Morrison's crashing realities and absurdity, and never failed to transmit the message that, odd as they were, the Doom Patrol were people who struggled and hurt and loved.

Twenty-five years later, with thousands more pages of Morrison comics to compare it to and a world that gets stranger every second, Doom Patrol is still the weirdest superhero comic of all time. A love song for the marginalized, Doom Patrol is experimental, preposterous, hilarious, and hopeful. If you don't get it, you're missing the whole point: you don't have to.

More From ComicsAlliance