Generation TOKYOPOP: The Revolution Will be Translated

TOKYOPOP is over. Or, they've announced they are shutting down U.S. operations next month, which means they are already over in the collective consciousness of the comic book industry. Loss of licenses, failure to replace top-selling franchises, lack of a big media hit, and rounds of brutal layoffs have been telegraphing the end since at least 2008. The effect is less like a crashing plane and more like a prizefighter gracefully sinking to the canvas in slow motion, finally at rest after a long career of struggles. Flashbulbs exploding. Rubber necks twisting.

But it won't always be this way for TPop. Their legacy won't be that of a spectacle, but rather, a groundbreaking leader of the manga revolution and the evolution of comics in the early 21st century. They weren't the biggest success of the era, but they were the boldest, the wildest; the first to lead the charge.Before 2002, manga in North America was a curiosity. After 2002, it was a phenomenon. That year, the U.S. manga industry was infused with an infectious giddy, humid anticipation of...what, exactly, it was hard to say. Anime Expo 2002 was a mob scene, with the otaku tribe in full bloom. Japanese executives were everywhere. Everyone was following the money, and the trail ended in shiny pink Hello Kitty wallets. They belonged to young American girls in elaborate cosplay outfits, enthusiastically flashing peace signs with a sing-song "OHIO!"

Thousands of American kids had gone full blown manga crazy, and on what? A paltry diet of a few dozen titles. Everyone knew there was literally thousands of manga volumes in Japan, just waiting to be translated. Many of them were million-selling hits across Asia. Who knew what would happen when they were published in the US? The Japanese executives couldn't believe how rich they were about to get. They had eyes as big as their fictional protagonists.

ADV branched into publishing, starting with a US version of the otaku-bible NewType. Dark Horse's stalwart program reached a new level with definitive editions of Lone Wolf and Cub and AKIRA. Viz debuted Shonen Jump, a monthly manga magazine packed with blockbusters like Yu-Gi-Oh! and Dragonball Z. Jump was such a monumental undertaking, Japanese publishers Shogakukan and Shueisha had to put aside a century-old family feud to make it happen. Even Marvel was getting in on the game with their Mangaverse event. Everything was happening.

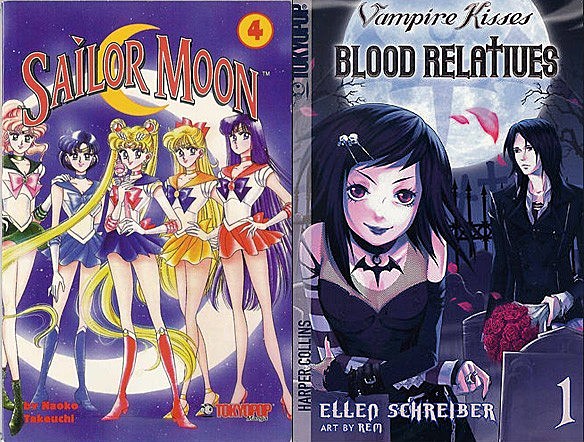

Tokyopop's contribution to the Class of 2002 was considerably more indelible. High from the eyeballs and dollars of Sailor Moon, the company launched a bold new publishing initiative: 100% AUTHENTIC MANGA. Japanese comics had been published in America for over a decade, but Tokyopop was out to redefine what authentic manga was all about. Previous to 2002, publishers in the U.S. tried to make manga look like comics. They'd mirror the pages and occasionally color them, to mixed results. They'd split up the notoriously long serials into 22-page monthly issues. The schedule was an emergency brake on the deliberately-paced stories, originally created to be read on a weekly basis. When collected into books, the prices were often north of $20, making it prohibitive to follow a story that could span ten, twenty volumes. And more often than not, the genres were limited to what American publishers thought the pre-existing readership would like. All U.S. fans saw was a couple narrow slices of the expansive spectrum of stories the Japanese were telling to great success in Asia.

Tokyopop's big idea was to make manga look like manga. Every book was digest-sized, over 100 pages a pop, with paper barely superior to newsprint. They maintained their original right-to-left orientation, which so many comic book readers in America had rejected for a decade as too disorienting. The artwork remained in black and white, with untranslated sound effects.

Truly, Tokyopop books looked and felt like a Japanese product and not a hybrid bastard: 100% AUTHENTIC MANGA. If "authentic" happened to be the same thing as "cheap and quick to produce," at least it allowed Tokyopop to publish each thick volume on a monthly schedule and at an affordable $9.99 price point. The whole concept was so unconventional, most American comic book industry watchers would have bet against the whole program, if they bothered to bet at all.

But Tokyopop wasn't targeting the American comic book industry, they were targeting the girls with the Hello Kitty wallets full of disposable income. Their new line embraced a wide range of genres, with a particular, emphasis on shojo manga -- comics aimed towards young females, many of them created by women. It was a crisp contrast to guy-focused American market. Finally, girls had stories that spoke to them, and they responded by joyfully consuming manga in huge quantities. It was something of a minor miracle in the U.S., where females had not read comics in great numbers since the 1950s. It had been that way for so long, some people claimed that girls inherently didn't like comics, and reaching out to them was a waste of time. Tokyopop proved them wrong in a big way, and the notion of the typical comic book reader changed dramatically.

The other frontier stormed by Tokyopop was the coveted bookstore market. Big chains were placing huge orders and dedicating yards of valuable shelf space to Tokyopop's cheap and popular manga. A whole new world, and a whole new audience, was now open for business. Others, notably Viz, scored major successes too, but it was Tokyopop that broke the dam. The "Tokyopop format" became a term of art amongst publishers looking to tap into this lucrative market, and comics had conquered new territory.

I had an unusual ringside seat to the whole scene. I was the American consultant for Gutsoon! Entertainment. In 2002 we launched a weekly manga anthology called Raijin Comics. If neither name is recognizable to you, it's forgivable; Gutsoon! would be out of the American market by the middle of 2004. Obviously, competing with Tokyopop was an intimidating experience. Their bullpen was a crack squad of sharp and enthusiastic editors. They were the Inglourious Basterds of manga, producing thousands of pages a month with ruthless glee. In the face of an industry of naysayers, they had an indefatigable faith that the march of history was on their side. They had a near-telepathic bond with the audience and booksellers. If there was a new sub-genre or archetype caching fire, you could be sure they already had three series underway. They were so nimble it seemed as if they could evolve their strategy on a daily basis.

And they had the books. Even back then, convincing Japanese manga creators and publishers to trust Americans with their babies could involve months of careful manners and patience, a problematic biz-dev ballet. But Tokyopop had the ability to license miles and miles of manga at a time. They had the magic touch, the pole position, the cat bird seat.

Tokyopop fostered not just a new generation of readers, but of creators as well. The publisher sought to publish manga-influenced comics by international creators, in a new line dubbed Original English Language manga. It proved to be one of their most controversial initiatives. On the plus side, they published strong, early work by emerging voices such as Felipe Smith, Becky Cloonan, Brandon Graham, Dan Hipp, Eric Wight, and Ross Campbell. On the minus side, the creators were bound by unusually strict contracts that took away much of their rights to the work, which Tokyopop seemed to cast into a fierce marketplace without much support. The line died before much of the bright, engaging comics were fully published, more from lack of nurturing than actual failure.

Behind it all was Stuart Levy, the founder and captain of the ship since the late 1990s, an exuberant pied piper of manga; Stan Lee with a MySpace account. The company took much of its restless, renegade energy from him. Levy was a fan from way back, picking up manga during time abroad in Japan. At Tokyopop, he put the fans and the content first, disregarding traditional wisdom about comics publishing. It was an attitude that allowed Tokoypop to boldly experiment, thrive, and lead. Levy's vision that drove Tokyopop to the top of the manga heap.

The glory days, unfortunately, are over. Public comments from Tokyopop executives since last week's shutdown announcement make it clear they don't see themselves as losers, or quitters. They seem to see themselves as something closer to my father's much-quoted definition of a pioneer: someone pointing forward, with an arrow sticking out of his or her back. The price of the trailblazer While Tokyopop's status as an innovator is certain, the cause of death is certainly more complicated.

Levy, like many transformational figures, has his detractors. He has been accused of business mismanagement and/or incompetence, corporate A.D.D., using comics as a back door into Hollywood, overworking employees one day and then imperiling their jobs the next, and a quirky brand of cheerful assertiveness that charmed some and pissed off others.

The question of O.E.L. rights is a prominent target. The original creators are keen to take their unpublished work elsewhere, but are contractually unable to do so. Legally, it seems likely Tokyopop is under no obligation give the rights back. Financially, it would be against their interests to let go of intellectual property that could earn them money in the future.

Ultimately, it may come down to a more mundane question: does Levy care enough to pay the lawyers to figure it out? Whatever the answer might have been, his attention is now elsewhere. In a remarkable turn, he has spent the past month personally trucking humanitarian aid to earthquake- and tsunami-stricken ares of northern Japan, and helping victims rebuild their lives. Online comments confirm his intention to film a documentary of the recovery.

The recent natural disasters in Japan and the collapse of Tokyopop seems to have sparked a humble, even spiritual awakening within Levy. The manga-fueld fan, the tycoon of Japanese culture, returned to his second homeland in a time of need. But what about those he left behind? Will he continue to hold onto the rights to the OEL manga during this new chapter? Is he businessman, man of the people, or both?

Whatever the answer, Levy seems finished with Tokyopop, tired of the American market, and comfortable with his legacy, for now. Should any, or all, of the accusations against him prove true, he is far from alone. There's an uncomfortably large group of figures in comic book history guilty of the same transactions. But it is in his achievements, in his innovations, that he stands alone.

The Tokyopop story is far, far from over. If you were 10-years-old in 2002, you will have turned 18-years-old last year. An entire generation of comic book fans are becoming legal adults, leaving behind childhood, and making decisions that will decide the course of the rest of their lives. Where they will go to school, what will study. Where to spend the money from their first legit paychecks.

Tokyopop is no longer here to grow up with them. Who is picking up the slack? What are they reading, and where are they buying it? What visions are captivating their interest, what voices are speaking to them? Do they dream of making comics of their own? Will they help create the next wave of comic book fans, like Tokyopop did before them? Or will they walk away forever?

There are tens of thousands of the Tokyopop generation, a baby boom of new comic book fans. The impact they will have could be historic, provided they stick around. Will the stay, or will they go?

Sam Humphries is a comic book writer living in Los Angeles. His projects include Fraggle Rock, CBGB: The Comic Book, and the upcoming Our Love Is Real. In March, he was named by Wizard one of "Five Writers to Watch in 2011." You can find him online at: www.samhumphries.com.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Simon Baz And Jessica Cruz Meet Doctor Polaris In ‘Green Lanterns’ #19 [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/GLs00.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Sam Humphries On The New Era Of ‘Green Lanterns’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/05/GL-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![‘Attack On Titan Anthology’ Unites Manga And Western Comics Artists [Exclusive Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/04/AOT-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![Celebrate the Worst Valentines Day with Sam Humphries and Caitlin Rose Boyle in ‘Jonesy” #1 [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/02/jonesy.png?w=980&q=75)

![Cast Your Vote For ‘Citizen Jack': Exposing the Horrors of American Politics [Review]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2015/11/Jack00.jpg?w=980&q=75)