Dangerous Art: Jeff Lemire on ‘Bloodshot: Reborn,’ Comics With a Point of View, and His Career

In his decade-plus as a comics writer and artist, Jeff Lemire has worn a lot of different hats: Indie darling, trailblazing Vertigo comics creator, DC Comics' go-to superhero writer.

Now, he's found something like a middle road. He's got a superhero book with an indie flair (Hawkeye), a creator-owned book with big sci-fi ambitions (Descender) and a new Valiant Comics series unlike anything he's ever done before: Bloodshot: Reborn, which is such a vastly new take on the character that plot details are hard to come by.

We talked with Lemire about his somewhat daring take on Valiant's most violent character, and also posed some questions about his varied career.

ComicsAlliance: I’d like to draw a line between some of your earlier work, your creator-owned work, to what you’re doing now at Valiant, Marvel and Image. You’re certainly not the first creator to go from independent comics to more mainstream work, but do you see one as informing the other?

Jeff Lemire: That’s part of a bigger question with a bigger answer, I think. I started out doing my own, creator-owned, independent stuff that I was self-publishing and writing and drawing myself, then going to Top Shelf and doing Essex County and Underwater Welder. Those were very personal stories, much more grounded. They weren’t genre stuff. To go from that to doing stuff like Sweet Tooth, which is a little more genre-based, but still very much aesthetically like my other stuff.

Then the DC stuff over the last few years — I spent four, maybe five years working at DC, and there’s some stuff that I did there that I’m really proud of, Green Arrow and Animal Man in particular. Both of those series, I really was able to put my point of view into them and make them my own, but I did start to feel like things were starting to move a little far away from some of my earlier work, so that was part of my decision to do the stuff I’m doing now, which is returning to more creator-owned stuff — stuff at Image like Descender and some stuff I have coming up later this year — and the projects I chose that weren’t creator owned, things like Hawkeye and Bloodshot. I consciously looked for things that I could inject a little more of my sensibilities into.

It’s not hard to see a direct link between Hawkeye and Essex County. The rural upbringing of Clint Barton, and stuff I’m doing like that. It’s very personal and you can see a real connection there.

Bloodshot’s a bit different. Bloodshot, for me, was unlike anything I’d ever done before, which was really the draw of it. In addition to trying to reconnect with my earlier work, I also wanted to try to do something that was completely new and different. I can’t see a direct line between things like Essex County and Bloodshot — maybe someone else can — but for me, it’s completely new and kind of exciting. It’s a little bit scary to do that book. I’m taking chances and going to some pretty dark places. It’s nice to have a vehicle where I can do that, because I haven’t had that in the past.

CA: It’s a little hard to talk about the details of the plot of Bloodshot: Reborn, because it spins out of the how The Valiant ends up, but one thing I think it’s safe to say is that you’re portraying Bloodshot in this series as a character who is seeing his past through a different lens. A lot of his reaction is to be horrified by it. I feel like, if there is a way to connect that to your earlier work, there’s a thematic sense where characters are horrified by the violence that people can be capable of.

JL: I can see that. Sweet Tooth, especially. To me, Bloodshot was unique and interesting. How he’s been treated in the past was as this ultraviolent killing machine. Quite frankly, that’s what he is. That appealed to me very little. That’s not the kind of stuff I enjoy or enjoy writing, so when I started to think about using Bloodshot as a way of commenting on that kind of stuff, commenting on violence or pop culture’s obsession of violence, issues like gun control and things like that, that’s when it became interesting to me, to use this character as a vehicle to comment on himself.

It’s not all about making some political comment, either. He’s also a fascinating character because he is almost a modern Frankenstein who has had these horrible things done to him, and as a result is forced to do horrible things to other people. Pull that rug away, and like you said, he can suddenly stand back and see what he was, and he’s horrified by it. He’s horrified by this life he’s lived and all the violence he’s perpetrated. Now, he’s trying to come to terms with that and see if he can become something else, if he can be something more. For me, that’s a very interesting character study.

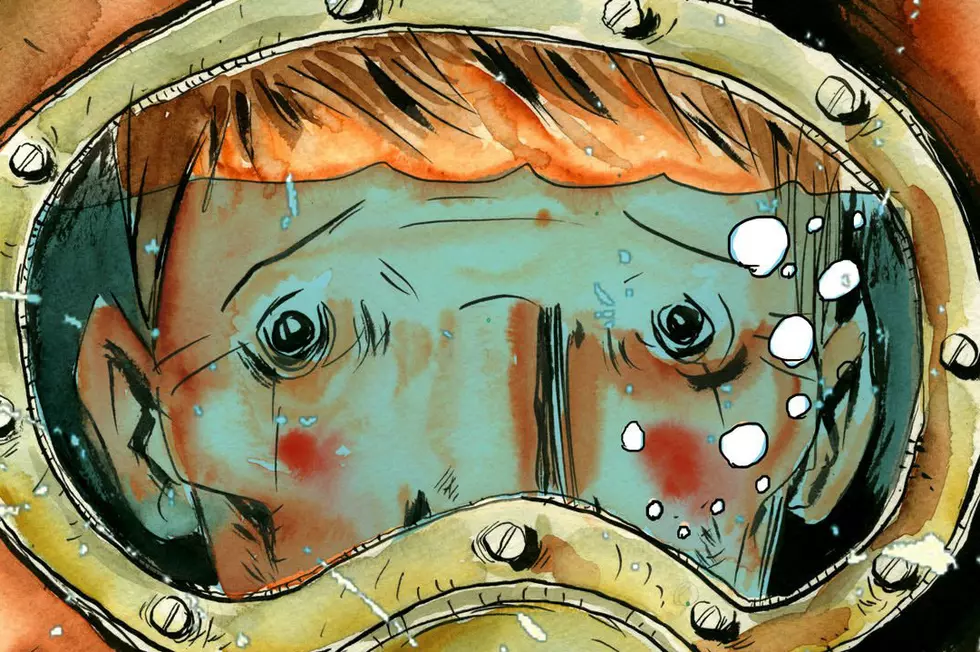

CA: One thing that’s really interesting visually about these first two issues is how, most of the art in it is by Mico Suayan, but every once in a while you pop in and add some art to it as well. It almost adds a surreal element to the book. What made you decide to add in your own art, and how did you work with Mico to put that together?

JL: It’s hard to talk about it without spoiling what it is I’m drawing in the book, but it is a pretty surreal element to the book. Bloodshot is very much under stress and taking many substances to try to cope with that. There’s an element that pops up and becomes a recurring thing that I draw.

Why did I decide to do it? I don’t know. It just seemed like I had to do it, because I came up with this idea. Who else would do it?

Technically, it’s easy. Mico knows which panels I’ll be doing that in, so he leaves a space, and when his art’s done, I almost trace over it and add my stuff. Then we composite it digitally.

It’s a way of me making a more personal connection to the character and the book. Normally, the work-for hire that I’ve done, I’ve never drawn any of it, except for one issue of Animal Man. The book, I’m very invested in it. This is a way of showing that, I think.

CA: Now that The Valiant is finishing up, there’s sort of this feeling that the you and Matt Kindt are splitting up the various elements of the book between yourselves. Did those things just kind of fall into place?

JL: It kind of came about, almost in the reverse order. Before we started working on The Valiant, I knew that I would be writing Bloodshot, and Matt knew he would be doing Ninjak and Unity, so we kind of had our own characters and knew where we wanted those characters to be at the starts of our series. The Valiant became a way for us each to set up our books, but also tell a satisfying story in The Valiant on its own. We already knew which characters we owned, so we proceeded accordingly.

CA: Considering that Bloodshot as a killing machine wasn’t the most appealing idea to you, and since so much of Bloodshot Reborn takes place in the character’s mind, how do you get inside his head? I get the sense that’s not your experience, being a military guy —

JL: I was not a military killing machine, no.

CA: [Laughs] Certainly Bloodshot’s an extreme, but there are people who have had those kinds of lives. How do you talk in that voice?

JL: I don’t know. That’s what it is to be a writer, to have different characters and not just write yourself all the time, you know. How do I get there? I go to a pretty dark place, for sure. I’ve certainly been in dark spots in various points in my life, and I’m sure I’m drawing on them, and exaggerating them and amplifying them for the sake of drama. I think I go to my anger and my own outrage at the state of the world, and filter that through him. That’s how I get there.

You look at the violence that you see every day when you wake up and look at the newspaper or online. You see things going on across the world, the injustices and the way we treat each other, you know? It’s not hard to feel pretty dark some days, so it’s not hard to get to that spot for me.

CA: There’s a sense of being ripped from the headlines in this book. In the first two issues, you certainly allude to some of the mass shootings that have happened over the past decade or so. In particular, there’s a mass shooting that happens in a movie theater, which immediately makes one think of the shooting in Aurora, Colorado. Did you want to make a direct comment on that particular type of violence?

JL: Yeah. It’s there. There’s no hiding it. It’s part of the book, and it’s pretty overtly and bluntly part of the book. You look at the cartoon violence we’ve seen in something like Bloodshot previously, especially the ‘90s incarnation, where it was just ridiculous and over the top, and you look at violence in the real world, the world we live in, the world where I send my son to school every day, and you see how horrible actual violence is. There’s nothing exciting or titillating or adventurous about it. It’s horrifying and terrible.

The mass shootings that have occurred in recent years, what more horrifying example of it is there than that? If I was going to tell a story where I was going to talk about these things, why beat around it? Why not directly address it and use this character who would normally be this comic-book action hero to talk about these things and use that as a metaphor for these things?

CA: Do you view addressing an issue like that, which has directly and indirectly affected a lot of people, as a walk on a tightrope?

JL: Art should walk a tightrope. That’s what art should be. Art should be dangerous. You can’t be scared to say something with it. People love to talk about how comics are real art and real literature, so why not use these characters to talk about real things, even if it is dangerous?

If some people take it the wrong way and don’t understand what I’m trying to say, I can’t control that. Is it walking a line? Of course it is, but it’s a line I’m very conscious of. I definitely have a point of view. As long as you go into it knowing what your point of view is, and being consistent, and never doing these things just for the sake of plot, or shock value, or for story, but actually use them because you have something to say about it, you go for it.

CA: There’s also an aspect of cultural criticism, where you’re commenting on cartoon or TV violence. Are you planning to say something overt about the consequences of the way people take in violent images day-to-day, or are you going to leave a lot of that to the reader?

JL: I think it’s pretty overt. I don’t leave a lot of room for what my opinion is, but you obviously want to let the reader do some of the work and interpret things themselves, too. You want it to be a conversation between you and the reader. You don’t want to get up on a soapbox and dictate things. That’s not going to be very compelling for anyone to read.

There’s a certain amount of mystery to the book that comes out of the interpretation of what’s really happening with Bloodshot, and what isn’t. There are layers to it that hopefully cause the reader to engage and think about these things and try to figure out what it is I’m trying to say and how I’m saying it rather than me just preaching.

CA: There’s definitely a vast gulf between the parts you’re drawing, which have a cartoonish style, and Mico’s art, which is exceedingly realistic. It’s almost photographic. Did that drive any of the story?

JL: It was more the other way around, where I knew exactly what we wanted to do, so we chose an artist that fit that. We’re talking about real things, and we’re trying to comment on things that are happening in the real world, so it made a lot of sense to find an artist whose work was very photorealistic like Mico’s, like you were looking at real people rather than drawings.

The element I draw — my natural art style is very cartoony, but it’s even a level beyond my normal drawing style, where it’s basically a little Richie Rich character. [Laughs] That’s a very conscious thing, to pick someone like Mico, who couldn’t be further from that style so you get that incredible contrast on the page, because if we had an artist with a bit cartoonier style on there with my art, it wouldn’t feel like there was a strange element in the “real” world.

CA: We started by talking about your varied career. When you were working for DC, you were doing lots of different titles at once, so juggling several titles isn’t necessarily new to you, but I do wonder how you keep all those plates spinning, with your mainstream work and creator-owned work, without one project bleeding into the other.

JL: Sometimes projects bleeding into one another can be healthy, but generally I do keep things very separate. While the workload on a monthly basis does look pretty intense, I’ve developed this working method where I get really, really far ahead on everything, like months again.

Like, for instance, I’m writing Bloodshot #12, and issue one hasn’t come out. What I do is I’ll just get really into Bloodshot for a week or two, and that’s all I’ll think about and I’ll work on. I’ll get all my ideas and all my energy for that project out and on the page. I’ll write one or two scripts. I’ll kind of burn myself out on Bloodshot and put that aside, and I’m so far ahead that I can put Bloodshot aside for two or three months and work on Hawkeye or whatever I’m excited about next or whatever I’m starting to get new ideas for. I just kind of toggle between them like that.

Being so far ahead allows you the freedom to kind of go with what’s hot at the moment and what you’re getting ideas for while you let the other ones sit. Letting a project sit and coming back to it is just as important as working on it all the time. You need to come back to it with fresh eyes.

Really, I only write one script a week. For instance, this week, I’m back on Hawkeye, so I’m going to try to do two or three Hawkeye scripts over the next two weeks to get that next wave of ideas and energy for Hawkeye down, and then I’ll burn out on Hawkeye and move on to Descender. It’s all about being really organized and getting really far ahead on things.

Starting a lot of projects at once, like I was, it’s been hard to get really far ahead on everything, but once you do, it makes everything a lot less stressful.

CA: It almost sounds like it’s beneficial for you to have several different projects going at once.

JL: I wouldn’t know what to do without them I’m a bit of a workaholic. I always have to have something, or I just don’t know what to do with myself. I need three or four projects, at least, just so I can bounce like that. It’s how my brain works and how I keep excited about everything.

CA: It also seems to guarantee long runs on books. If you’ve got 12 issues of Bloodshot in the can, that means you’re going to do at least that much Bloodshot.

JL: Bloodshot is a weird one. I’ve got 20-something issues of Bloodshot plotted out very tightly, with stuff already being worked on because we’re going with different artists on each arc. There’s like this 20-, 25-issue plan that’s going to happen. It’s already in the works.

That’s good. It’s good to have a publisher like Valiant that’s confident enough in me and trusts me enough to go that far ahead, follow my vision and support it, instead of having to hand in an outline every three or four issues and wait for it to be approved. It allows you to think bigger, plan bigger and take bigger risks. I really like that.

Bloodshot: Reborn #1 is on sale April 15th.

More From ComicsAlliance

![All The Image Comics Announcements From Emerald City Comic Con [ECCC ’17]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Image-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![Comics Alliance Rates The Avengers Hunks [Love & Sex Week]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/02/marvelhunks-feat.jpg?w=980&q=75)