![Activist Bill Ayers Talks About Teaching Comics [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2012/04/toteachcomics.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Activist Bill Ayers Talks About Teaching Comics [Interview]

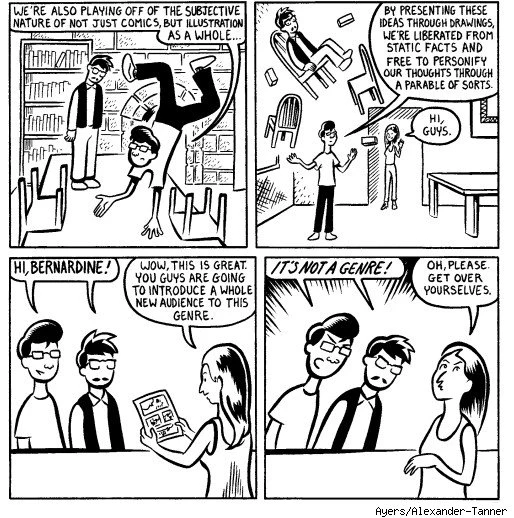

Best known as a co-founding member of the radical organization The Weather Underground, Bill Ayers has spent the last few decades as an education reformer who has committed his life to changing the way public schools teach students. Now a retired professor from the University of Illinois at Chicago, Ayers has written numerous books on how to change the learning process, including To Teach: The Journey of a Teacher, which was adapted into an original graphic novel. To Teach: The Journey, in Comics reads as a story more than an instruction manual, and details the obstacles a young teacher must overcome in order to engage his students. Praised by independent creators like Harvey Pekar and Peter Bagge, the graphic novel will be taught as workshop this weekend at Portland's Stumptown Comics Festival, where Ayers is special guest.

Ayers spoke with ComicsAlliance about adapting his book, the importance of comics in political discourse, and what attendees to the festival should expect from his workshop.

ComicsAlliance: What made you want to turn your original book into To Teach: The Journey, in Comics?

Bill Ayers: I'd read comics all of my life and even used graphics in my college teaching, so I'd like to say the inspiration leapt full-blown from my head, but the truth is a little more wobbly. I was asked by my publisher to do a third edition of a book of essays that I'd written over 15 years before, and the thought of it bored me, so I responded glibly that I would do it if they would let me do it as a comic book. That was meant to end the conversation and finish the matter, but a month later they said OK, and the journey began. I never thought I would be involved in writing a graphic novel, and I'm still a bit surprised and elated by the whole thing.

CA: How did you start working with artist Ryan Alexander-Tanner?

BA: Working with the dazzling Portland artist Ryan Alexander-Tanner was a joy for me as well as a powerful education. When we went looking for a comic artist, my publisher had a lot of more established folks in mind, but I remembered that my younger brother had had a student in high school who handed in a lot of stuff in comic form-quirky, original, irreverent. The kid had gone off to art school, and was living in Portland. We connected, and it was pretty much love at first sight. He moved to Chicago, and lived with us for several months while we worked on the project.

What a wonder! I'm a slow learner and a bad student, but Ryan was patient and nourishing. It took a while for me to really get the fact that we were writing an entirely new book, not an illustrated version of something I had already written, and not a floppy gateway drug into the "real" To Teach. He insisted from the start that the comic would be as nuanced, complex, dense, and profound as any book on teaching ever was. Our writing process included lots of late night pizza and other mind-altering experiences.

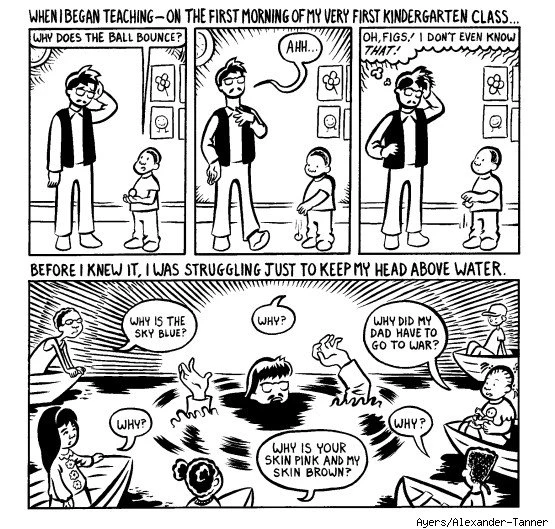

This fictionalized account captured the main ideas of the original essays, but now with characters and plot, a beginning and an end, tension and drama and resolution. The novel opens with the story of a young teacher stepping into his first classroom on the first day of school, experiencing the distinct sensation of drowning, and then struggling to swim, unsteadily at first, to a distant but reachable shore. By the end of the book he has become a teacher of some substance and certain purpose.

For me our process involved learning when the drawings can do the work and when the words had to carry the weight. I had to understand that the original could be recast as a story, and I had to learn the power of concision and compression. Ryan really is kind of a genius, not just as an artist, but as a writer and as a teacher as well; he taught me a lot in this process, and together we created a world within a classroom with all its messiness and burgeoning ideas, its academic demands and social convolutions.

Looking at the finished product, a comic book about teaching seems somehow just right to me now-the intimacy of classrooms, the aesthetic and the feel of being an educator, the challenge and the joy, the pain and the promise-all of it tough to describe, and represented here with a distinct immediacy. We try to offer a pathway into the ineffable, relying neither on words nor images, and not mashing pictures onto words, but a third thing altogether with its own opportunities and demands-words and images working together in a dance of representation and meaning.

CA: What are some of your favorite comics?

BA: I began reading comics early, and like a lot of suburban kids growing up in the soft illusion of 1950's suburbia, I was an instinctive anarchist. Mad Magazine was a canonical text that let me know that, while I was surely subversive and I may have been crazy, I was not alone in the world. My love of comics grows and grows: [Robert] Crumb, [Art] Spiegelman, [Marjane] Satrapi, [Joe] Sacco, [Alison] Bechdel, [Chris] Ware, [Lynda] Barry, [Ryan] Alexander-Tanner... . I'm so happy to be alive in the most propulsive and yeasty moment, diving every day into the wide wide universe of comics.

CA: You're a special guest at this year's Stumptown Comics Fest in Portland, OR. Can you talk about the two panels you'll be on -- one about using comics as an educational tool and one about comics and politics with syndicated cartoonist Matt Bors and writer Sarah Mirk -- what will attendees be able to learn at these sessions?

BA: Let's wait and see. I'm sure I'll learn a lot. But I do hope that people see that teaching at its best is profoundly intellectual and ethical work, filled with joy and challenge, agony punctuated with moments of ecstasy, and certainly that all the ideas of teaching as clerking are not only reductive and morally repulsive, but they are also aesthetically empty, unappealing and unlovely, and entirely unworthy of our deepest humanistic dreams.

I've been a teacher, a peace activist, a trouble-maker, an artist-in-residence, and a work-in-progress for many decades. As a life-long comics reader and a serious fan of the medium, I'm happy to be experiencing a rebirth of sorts as co-author of a comic book, and honored and privileged to hang out with you all at Stumptown.

CA: Why are comics important to education? Why are they important to politics?

BA: Teachers need to recognize that teaching has an aesthetic- they might be nudged to strive for beauty and something pleasing and lovely in their work-and that the opposite of aesthetic is anesthetic. Wake up! Get moving! Nourish the imaginative and the weird and the queer! Art urges voyages of discovery and surprise. The comics world, on the other hand, might give teaching a chance too-I hope one fine day a zillion artists and marginalized bodies will flock into classrooms to lend a hand.

Of course teachers should use comics across the curriculum, just as they might use film or poetry or painting. I can't imagine teaching the Middle East without Sacco, the holocaust without Spiegelman, gender without Bechdel. The value is simply that graphic novels are part of the wildly diverse, wacky, and rich gumbo of our culture. If you were teaching a history class today on the Holocaust in Europe, you would mobilize memoir (Ann Frank, Elie Weisel) essay (Hannah Arendt, Thodore Adorno), and film (Shoah, The Sorrow and the Pity) to help students get a deep and meaningful, nuanced and complex picture of the entire sweep of the times and events. To leave out Maus would be to banish a fresh and intimate work that adds immeasurably to our overall understanding of the Holocaust.

Similarly Dykes to Watch Out For [by Bechdel] is an essential text if you hope to understand the recent years in America. On and on and on: teachers integrate poetry and literature, art and science, film and painting into everything they teach. Why not comics? I teach a writing class on memoir, and I use Maus, Persepolis, Fun Home, and Epileptic along with Homage to Catalonia and Black Boy. Students respond variously, but I would be irresponsibly narrowing their horizons if I left out the comic books.

CA: What are you working on this year?

BA: I'm working over-time this year on occupying this and occupying that, occupying the future and occupying my imagination, occupying everything in and out of sight.

Revolution is still possible, democracy and socialism, possible, but barbarism is possible as well. I'm trying to live leaning forward, a pessimist of the head but an optimist of the heart. I find the tools everywhere-humor and art, comics and poetry, protest and spectacle, the quiet, patient intervention and the angry and urgent thrust-but the rhythm of activism remains the same: we open our eyes and look unblinkingly at the world as we find it; we are astonished by the beauty and the suffering all around us; we recognize that right next to the world as such is a world that could be or should be; we dive into the wreckage and swim as hard as we can toward a distant and indistinct shore; we doubt that our efforts make enough difference, and so we rethink, recalibrate, look again, and dive in once more. If we never doubt we get lost in self-righteousness and political narcissism-been there. If we only doubt we vanish into cynicism and despair. Awake/Act/Doubt! Repeat for a lifetime.

Oh, and I've got two new books on the way: Palling Around: Talking with the Tea Party, and What If? Releasing the Radical Imagination.

Exciting times!

More From ComicsAlliance

![Sweden’s Peow Launches its 2016 Line-Up Through Kickstarter [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2015/11/peow-feat1.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Tim Seeley Talks Celebrity Culture And Small-Town Spookiness In Vertigo’s ‘Effigy’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2015/01/EffigyHeader.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![ReedPOP Goes In-Depth On Plans For New York Super Week [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2014/06/Untitled-149.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Crowd Funding Watch: Ryan North Remixes A Shakespeare Classic With ‘To Be Or Not To Be’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2012/11/untitled-1-1354047913.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Jeff Parker and Erika Moen Talk the End of Portland Mystery Comic ‘Bucko’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2012/02/2011-04-14-bucko23.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Paul Cornell on ‘Soldier Zero,’ Stan Lee, and Crowdsourcing [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2010/10/soldier-zero-sex.jpg?w=980&q=75)