Duet On ‘Solo’, Part Five: Darwyn Cooke

Published between 2004 and 2006, Solo was a DC Comics anthology series with an innovative twist: each issue was created from the ground up by a single cartoonist and collaborators of his own choosing. Edited by DC's head art director Mark Chiarello (Wednesday Comics, DC: The New Frontier), the series offered artists a platform to control their visions completely in the form of original stories, unfettered access to DC's library of characters, and without regard to continuity or other publishing concerns that affect the creation of a typical DC superhero book. Although Solo spotlighted the work of such talented and popular creators as Darwyn Cooke, Tim Sale, Paul Pope and Michael Allred, the series was cancelled after just 12 issues.

Even in a time when the superhero comics were experimenting wildly with structure and style, Solo stood apart and remains one of the best and most interesting mainstream series to emerge from the early years of this century. In this installment of Duet on Solo, writers Sean Witzke and Matt Seneca take an extremely close look at the fifth issue of Solo, created by Darwyn Cooke.

Matt Seneca: Fifth to the plate in the Solo lineup, and kicking off the second (and, I think, highest quality) third of the title's run, we've got Darwyn Cooke. Cooke's an interesting artist to see taking part in Solo for a few reasons: he had relatively few titles to his bibliography when this issue was published in 2005; he'd spent almost the entirety of his comics career working at DC and Marvel; and most pertinently, he didn't really need Solo editor Mark Chiarello's mandate to do whatever he wanted.

Cooke started his comics career at DC, did a grand total of one short comic, and then got snapped up by Warner Bros. Animation for the following decade, a period of time during which he art directed the visionary Batman Beyond series ('90s babies holla back!) and constructed both a basic cartooning ability and an understanding of nuts-and-bolts pictorial storytelling that most guys who spend their whole careers in comics never quite manage to put together. You can see Cooke's animation experience in his sequential work -- it really moves -- but he's also greatly suited to making art where the pictures don't move, with a knack for producing images that stand alone as well as they rhyme with their larger story context. He's one of the most highly skilled guys working in any area of comics right now, and known as a firebrand personality -- all of which comes through in this issue.

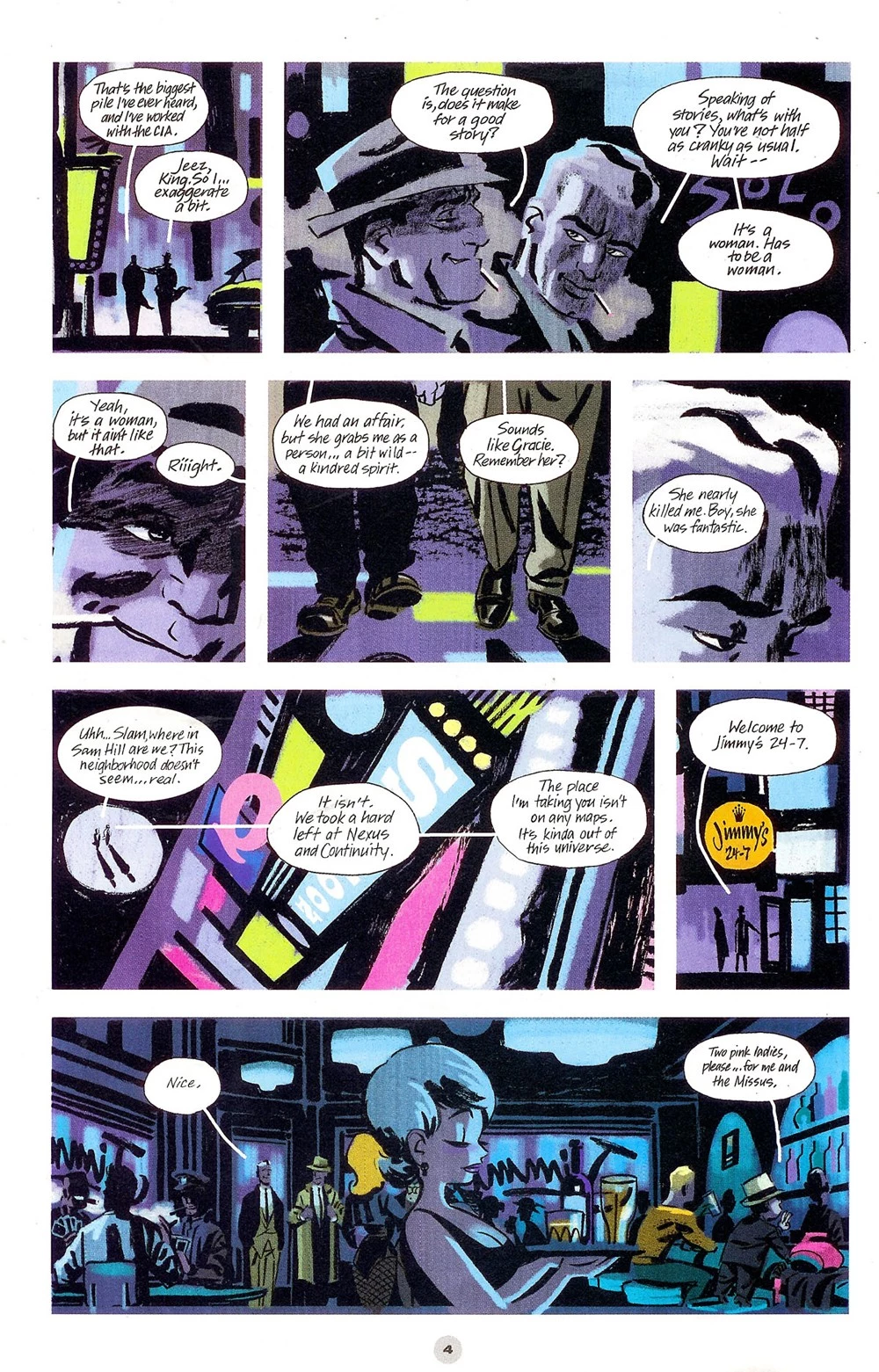

Sean Witzke: With respect to format, Cooke's the one who really explodes the Solo form with his issue, and from here on in the books resemble less and less that Tim Sale template and become personal showcases. Even Chaykin's Solo relied on a tried and true comics anthology format. Here, Cooke steps away from the traditional and goes for a nice fudge of magazine format and a series of shaggy dog stories, kind of Esquire/Playboy meets Canterbury Tales.

MS: It's still very much in the EC Comics mold, though -- only here we get Slam Bradley introducing the stories and providing witty meta-comments instead of the Crypt Keeper or the Old Witch. Which is appropriate enough: even though all the stories here aren't superhero-based, the DC Universe is still very much the comic's home setting, with the tone of hero comics kind of overriding even the strangest and most off-model stories.

SW: I really like that Cooke draws Bradley really close to a self-portrait, as a self-insertion point, and the pragmatic way that Bradley comments between the stories seems to be in Cooke's voice, with as much old detective drawl to make it in character.

MS: Those bridging sequences are probably my favorite part of the comic, actually, or at least right up there -- that's the stuff that first springs to mind when I think about this comic. Part of it is that they feel a lot truer than any of the stories, none of which are very memorable, content-wise. Even when Cooke drops the fictive veil and spins a little yarn about his childhood introduction to the arts, it's all told in such a... a narrative manner, I guess, that it reads as just another bit of light entertainment.

SW: It's the most Matt Seneca thing ever to use "narrative" as a negative, right there.

MS: The weird, rambling bar scenes with Slam Bradley and King Faraday, though, they're just sitting there on the page, colored with the most beautiful painting Cooke ever did in his career, kind of staring at you. It's not a mode of comics you often see -- like "superhero Harvey Pekar" or something.

SW: Well, there is a subset of stuff that's like bar conversation comics. Most Eddie Campbell and Garth Ennis comics have those kinds of scenes, but that's great company to be in, and Cooke seems just so comfortable with having those two guys talk to one another. Bradley and King, they're great characters for Cooke to get his hands on because they both are completely unlike the milieu they're played against; they're old characters from another time still here even after they've been replaced by superheroes and Cooke knows there's poignancy in that.

MS: I think you're touching on something important -- Cooke clearly adores those characters, and that pre-superhero man-of-action character type, too. You talked earlier about Slam Bradley as a kind of avatar for Cooke himself, and I think that really works once you start talking about idioms that have replaced one another in comics. Like Slam Bradley, Cooke is kind of a representative of a past point in history. The Alex Toth/Jack Kirby style he uses has been almost completely discarded within mainstream comics the way hard-boiled, non-powered leading men have, and you can really see Cooke glorying in the pulpy past all through this issue. Nothing here is really done in a modern style. There's the mid-century spy story, the knee-slappingly awful horror spoof, the paranoid spy thriller right out of the Robert Altman playbook, even the Batman story at the end is taken from a '70s comic that was itself going for kind of a '30s noir feel.

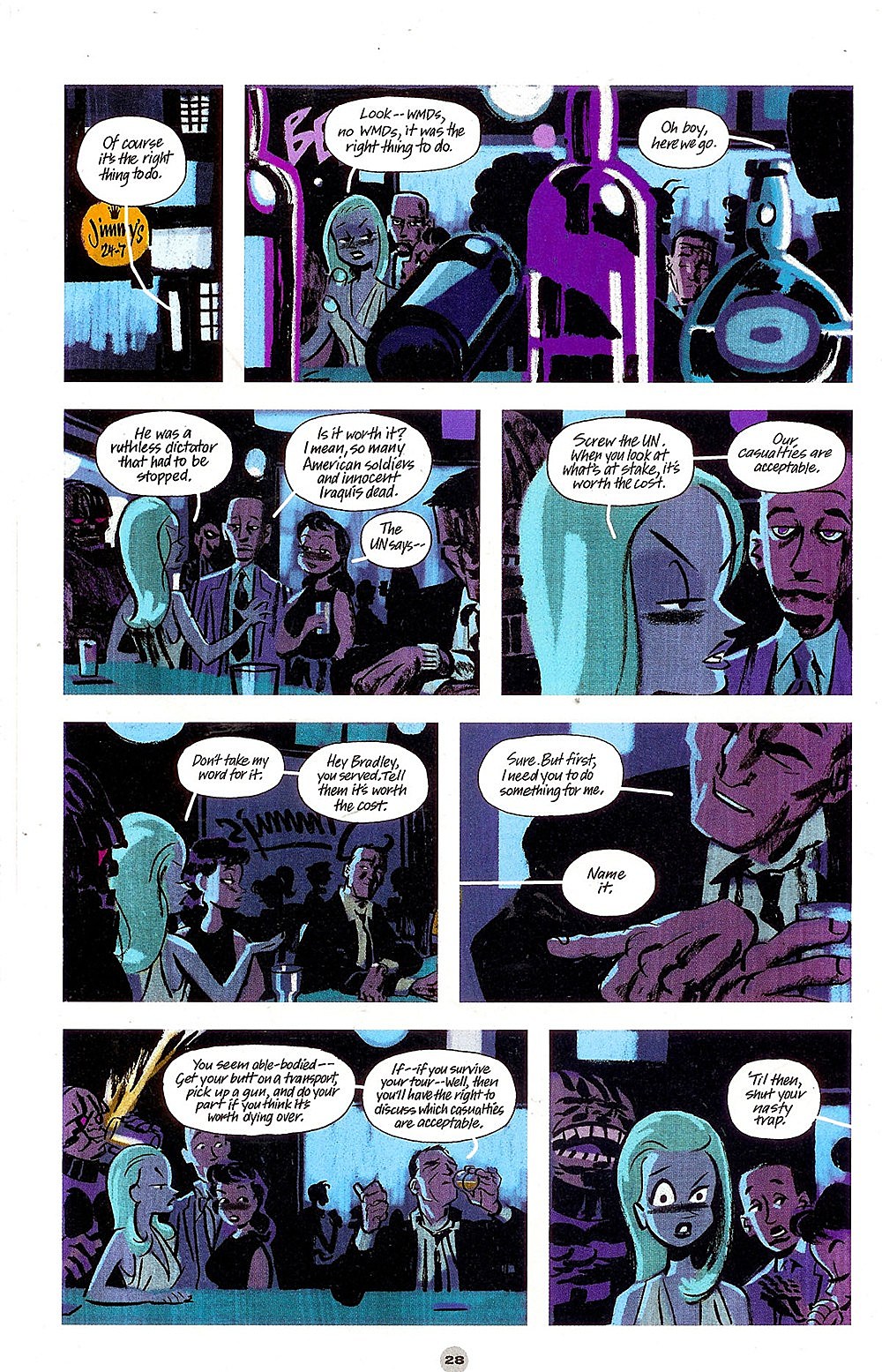

SW: The Question story seems to be playing at eating Frank Miller's lunch, right after The Dark Knight Strikes Again, especially with the way it uses intentionally ugly digital graphics as its center. Or at least with the tenor of post-9/11 superhero comics, which were just absolutely terrible at taking the idea of terrorism on directly, and Cooke did it in four pages. But yes, so much of it is done in styles that haven't been used for these kinds of comics in forever.

MS: That Question comic is really a fascinating piece of work. I have this theory that superhero comics could have just been so much more aesthetically relevant and capturing-the-zeitgeist-y if they would have all just shown superheroes going over to the Middle East and kicking al-Qaeda's ass. Like, if that had been every superhero comic for October through December 2001, with every character by every different creative team beating up the same group of a few hundred people, then the spectre that still really informs most of the worst superhero garbage we see today would have been well and truly dealt with. As it was, only Cooke actually showed a guy going over and killing the group of people directly responsible for 9/11, and then just peacing out. Four pages is all that's needed. And those digital graphics are amazing, especially in retrospect. It's everything that was ugly about early 2000s computer comics boiled down into one solid core.

SW: The Question has a history of really being such a fringe, alienated character that he's the only one that could be thrown into that situation without any hand-wringing or Frank Miller clout to do whatever he wanted. Either because of Rorschach, Question creator Steve Ditko's politics (which are reflected really simply and elegantly in four pages [really two-thirds of four pages, damn is it elegant]), or the Dennis O'Neill and Denys Cowan psychologically focused series, he's a character that would totally go and do that.

MS: Insofar as that personality formulation, The Question's another character type that's no longer much in use: the man who kills with moral certitude. It's a fascinating, fascinating archetype that's never really failed to produce interesting comics. The Question during the Iraq War, and even engaging issues right around the fringes of that, is interesting because Ditko really created him as a uniquely American representative of the moral right to take lives -- of the pre-emptive strike -- and here Cooke shows that action going down in a simple and elegant manner that I remember wishing could have been employed in real life. It's a hell of a comic. And the Craftone greys are gorgeous, too.

SW: Also, it addresses that Vic Sage was a television reporter originally. In the '00s, that would make him a willing participant in the War on Terror instead of a crusader in the War on City Crime. It's really smart, and really faithful to the nature of the character. And man, can he use some really gorgeous white in those pages. The first panel of the horse on the last page is probably my favorite drawing here.

MS: Yeah! This is really a four-page rehearsal for his Parker graphic novels -- all the instruments are here, from blue single-tone coloring to a completely heartless, calculating lead who we kind of root for despite ourselves.

SW: The introduction page to the thing, which is just Slam/Cooke dressing down Ann Coulter, and then following it with that story, it's kind of an introductory course on how to be clear with politics in a comic, whether or not it's something you as a reader agree with.

MS: I remember there being some pretty heated reaction to that page when this comic first came out. It is still slightly astonishing to me that DC published it so deep in the Bush era, but yeah, good for them. I do have trouble figuring out what political lesson we're supposed to take from the combo, though -- it's almost like a weird advocation for superheroics, or at least vigilante justice: the only position of moral value is acting by yourself on an issue you're absolutely certain of, no matter if it's murder or washing the dishes. Heavy stuff, especially in the middle of such a relatively light comic.

SW: I think that's ascribing one part of it to the other, actually, because the Coulter thing is Bradley saying you can't say it was absolutely right because you have no stake in it, and then follows it up with the logical extent of moral absolutism, where The Question is right but he's just so certain. I don't really think it's advocating vigilante justice as much as any Question story does (which is still a lot).

MS: Well, yeah, Ditko was absolutely in favor of the actions he showed the Question taking, or at least he gave every indication that he was. Maybe that's the core of the character more than any political formulation: show him taking an extreme action that you -- the artist -- can unequivocally get behind.

SW: Lets move from the most interesting thing here to the least, the autobiographical portion. It's a slice-of-life thing that is just so incredibly aspartame sweet that who could remember what happens in it other than sunshine?

MS: Yeah, it certainly looks like sunshine. The story of the adorable old lady who taught Lil' Darwyn Cooke to paint is incredibly painful to get through, it's so clichéd and whitebread. But flipping past it to get to the Question part just now, I will admit to having been struck by the transition from yellow and black and white to the parts that add in a blue-green tone. It's pretty nice-looking comics. But I don't know that there's even anything nice I can say for the story. It's not even interesting or objectionable in its low quality, it just sucks. Cliché dialogue, rose-tinted nostalgia, cardboard characterizations... Maybe it's good that he got it out of the way first?

SW: I think if I have to choose between this and Chaykin's version of "how I got into it," which is so much more playful, I don't know how you could say that this was good. I don't even know if it sucks but, man, is it vanilla. It's a lot of what people would say Cooke's books are far too much of, nostalgia and great cartooning. It's a good argument for story, right?

MS: Hell yeah. I actually think it isolates the problematic aspect of Cooke's particular brand of nostalgia, which is that he gilds a particular era so heavily in sappy sentimentalism that you never see the massive problems with society that were absolutely rife during that era (we're talking '50s and '60s here.) In Parker it's one thing, because those books are as much about how people were real awful back then just like they are now, but here it's like, "Ah, remember how much simpler things were before the civil rights movement?"

SW: I think he's more open to it in longer works, like DC: The New Frontier (which I think saves itself with one scene) and Parker (which gets so absolutely dire at times even when it's at its most ad agency shiniest), but in shorts, yeah its just so much fond memories. The vacuum story makes it look so good, though.

MS: Yeah, "Everyday Madness," about a dude who wants to have sexual intercourse with his vacuum cleaner, is a pretty awful piece of comics, but it's not as completely devoid of potential as the autobiographical short, which makes Cooke's mishandling of it all the more regrettable. It's like somebody told Cooke about the stuff Dan Clowes was doing in Eightball and he tried to make a comic in that same misanthropic, paranoid vein without ever actually seeing how that type of material can be successful. By far the most broadly cartooned thing in here, ruined further by a horrible computer-lettered font. It's got the smell of artistic compromise about it, like Cooke was too scared to play his story straight, which puts it greatly at odds with the best stuff in this comic, and not in a good way.

SW: He is totally having sex with his vacuum on the third page, which is the only good panel of the thing, with the power cord wrapped around the table leg. It's totally a Peter Bagge parody... but not? It's like, "Oh, masturbation jokes, got it," and then Cooke went and did something that's kind of... that. I think it could be funny if Tom Kenny (or Billy West, someone with that great authoritative '50s commercial announcer tone gone awry) was reading the narration but it's just so dead on the page.

MS: Yeah, all five of them, it goes on for ever and ever, with the color job getting worse all the time. I usually think of this comic as a pretty rich one, because of how high and varied the heights are, but then I get to those two stories and it really feels like Cooke didn't have enough steam to fill out a 48-page comic book.

SW: Which is nuts because he throws away some truly great ideas in the middle spread "grab bag" section. That history of mainstream comics strip on the bottom could have been its own thing with no problem at all.

MS: Yeah, I would have way rather seen that blown up into a five-page strip with two more illustrative frames per than anything in the vacuum thing. It's a pretty fantastic comic, although how bizarre is it that he starts his history in the 1920s? Even full-page versions of the Zatanna and Black Canary pin-ups would have been preferable, at least there's some first-rate cartooning there.

SW: I like that he put a full Catwoman pinup in there because I think it gets at the format he was going for really well. That they're all great pinups doesn't hurt.

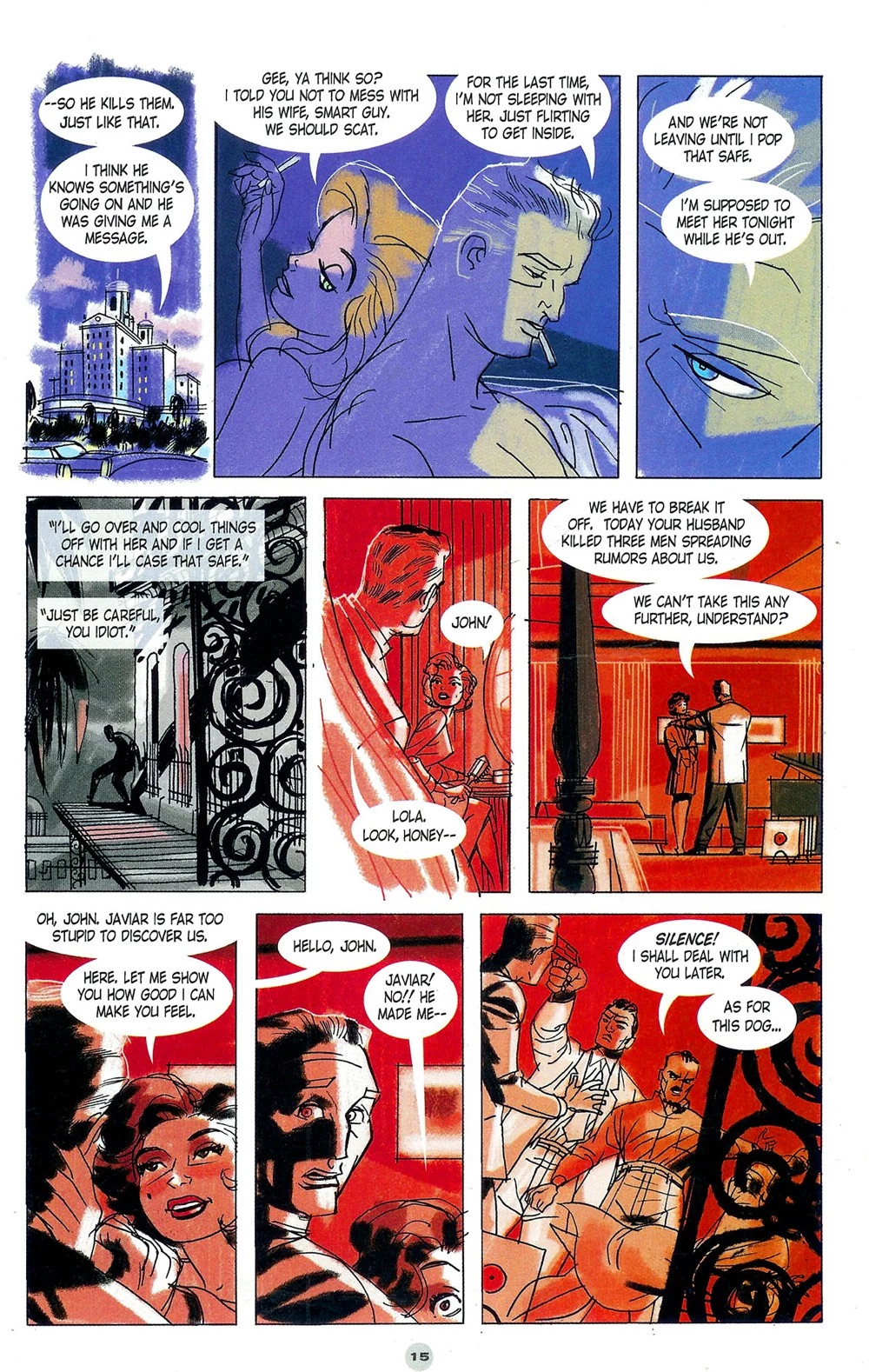

MS: Anyway, there's more good stories in here than bad, one of which is the King Faraday espionage adventure, presented to us as a wooly bar story being told to Slam Bradley by a much older Faraday. It's pretty standard pre-Castro Cuban intrigue stuff, but well drawn and ably told. It's also interesting because it's maybe the only thing Cooke's drawn with a pen. The mark-making alone in the story makes it worth the time -- wide open, clean and crisp, with an airy color job to match. Even the awful lettering (again) doesn't drag this one down.

SW: The opaque captions and balloons kill me. Other than that, it's really well done, but I have to say that five years and reading a few James Ellroy books in the interim really robs the thing of its teeth. I think Cooke uses the same style (of art and narration) to a lot more success in the first Parker adaptation, The Hunter, as well.

MS: For sure, it's a competent plot at best, but he does get it to propel some really great images: bodies falling off a tropical cliff drawn as just tiny little hatchmarks, a rifle exploding just above the head of its intended target, blue sunbeams just ripping into a hotel room onto a necking couple, the same couple back-to-back as they try to catch each other in opposing webs of lies. I think it comes off as so impressive the first time you read it because every page has at least one image that not only amplifies but enhances its content's quality.

SW: The lighting on page 15 where it's just shafts of light on their faces, but not clichéd noir lighting? That's a really amazing, almost '70s crime film touch that is so unexpected but just small enough for it not to be a big deal. I think it's decisions like that that take the piece up a bunch of notches.

MS: That panel's definitely my favorite one in there. You can really see Cooke's animation background in the way the color in this story moves the action forward by hovering around the figures rather than blocking them out solidly and holding them down -- and in the way every different scene has its own unique color scheme, too. It's one to look at more than read, for sure, but there just aren't a whole lot of comics that look anything like this.

SW: It is great that he assigns each story not just a style but a coloring identity of its own, so there's no way any of these stories run together when you're just flipping through, which is something you could say for a bunch of these Solo issues.

MS: Let's move on to the most impressively colored comic of the lot, then: Cooke's cover version of the Steve Englehart Batman classic "Night of the Stalker," which I'd imagine Cooke got into because of the amazing Sal Amendola art. They blew up a pretty routine, tightly plotted Batman thriller into a gothic nightmare. It's also, as far as I know, the original "Batman fails to prevent a crime similar to his own parents' murder from happening" story.

SW: The cover version is, I think, Solo's great gift to these guys, because it's obviously the most fun they have in the issue each time they pop up. Cooke clearly had an idea of how to attack this when he came to the show. There's a great little shot of the first robber looking like Steranko's Jimmy Woo on page 39 too.

MS: I love that panel. I always wonder about this story -- I don't know for sure, but I'd bet anything it's a storyboard for an unmade episode of Batman: The Animated Series repurposed into a comic. The drawings themselves work in a way that's a lot more filmic than comi-booky, each one hitting its own narrative beat before moving onto the next one, all of them pitched about the same distance in time from one another.

SW: What's the thing Alan Moore said? Nine panels is film, six is television? But eight is animation. I don't know why that is, but it magically makes the page bigger without sacrificing clarity. Alan Moore knows a whole lot about comics storytelling, huh?

MS: It's the shape of every panel: they're all just big enough to read as distinct, separated images, but small enough that you don't really dwell on them as drawings. It's why Jaime Hernandez has gotten so much better recently. This story actually reminds me a lot of Hernandez, with every image perfectly capturing the risen action of its scene perfectly before the next one does the same exact scene. It's why this story feels like such a barn burning, high-octane thing: every panel is just screeching at you.

SW: Casanova and Stray Bullets are built on that format as well, both of which feel designed to be read at a fast clip. Which is interesting because some of the best panels here are kind of given a bit of the shaft because of the awesome pacing (pacing control in comics is the hardest thing to do right but when it works, it's revelatory). The panel of the shotgun snapping, all in relief, followed by that great wide shot pull-back. It's master class framing/editing.

MS: Pacing control is always based off a simple, repeating layout. That's what makes this such a fantastic comic. But some of those images do... "bother" is too strong a word, they're all lovely, but they stick out. Perturb! They perturb me. You can tell Cooke drew these all way bigger than reproduction size, which is fine for the close-ups and the more simple, graphic shots. But on the wide shots the quality of the marks changes so graphically that the flow does get interrupted some. It's a minor thing, but it takes away some of comics' naturalism and imports a little of animation's contrived, slick feel. Also, none of these pages or images really play into one another to form an overarching whole. If you pull back and look at all eight shots on one page, there's not much internal symmetry or telegraphing of future panels going on. Everything is just happening on a screen.

SW: Did you read that interview with cartoonist Zack Soto where he was talking about intentionally reformatting/resizing Secret Voice for the web? I was shocked to see that I couldn't catch that in the reading. Not the way you can here.

MS: Well, Cooke goes for extreme polish on this comic -- which suits such raw, scary material really well -- but that's the downside, sometimes the shine off the gloss just dazzles you.

SW: I think the most effective panel is where he breaks the sheen a little bit with that giddy smile on the robber's face on page 43. It's not illustrative; its done for effect and it works so well.

MS: That's definitely the most frightening moment, like something out of Graham Ingels or Josh Simmons: pure horror comics for just a second. I actually think the opening tier, with Bruce Wayne's dead parents crossfaded over the dead couple who begin this story, is the best part, because it uses that highly elegant, refined drawing to achieve an elegant effect before going off into the more grindhouse stuff. That's where the cleanliness really works to establish a tone, and it doesn't let up for the rest of the story.

SW: It reminds me of Kiss Me Deadly, a lot. Tone mostly, no real similarities.

MS: Sin City is actually what I think of. The second panel in that sequence is just so graphic, with almost all the line work fading out and leaving just black, red, and white shapes.

SW: The coloring, the great deep red/orange/brown palette he's chosen, is what you wish most Batman stories would be done in.

MS: Another import from the animated series. Alex Sinclair actually did a fantastic job with it over Jim Lee on Hush. Trish Mulvihill over Eduardo Risso on 100 Bullets does a similar thing really well too. Yeah, quintessential stuff. We should mention that Cooke himself was the first to really bring the cartoons' palette into the comics when he did Batman: Ego.

SW: Comparing this to Ego shows how far Cooke went into streamlining his storytelling, because Ego is actually an interesting story that keeps getting tripped up on the storytelling. This is the opposite, where it's all about the execution and tone on a pretty regulation Bat-story, albeit a cover of the first of it's kind.

MS: Right, which is why it's important that Cooke didn't write a rehash but just covered an old story. It's not the specifics that count here, it's building the myth with repetition.

SW: You have to love the language of the thing, too. They keep calling Batman "The Devil." It's myth-building in a really smart way.

MS: I want to end this by doing something besides pointing out the fact that the strongest work in here is playing off someone else's creations was a sign of depressing things to come, but... I got nothin', besides maybe "good comic." You?

SW: Well, Kevin Church pointed out a few years ago that Cooke had a problem with not really coming up with anything, even though he's a gorgeous stylist. I think in the period between The Spirit and announcing the Parker books, and before we all saw how much Cooke did with the Parker books. And man, now we know Church was right. What does it mean when someone's greatest work is adapting someone else's novels? It probably means he's going to be okay with taking other adaptation jobs because he's not creating anything. How can you say, well he shouldn't be touching the Watchmen characters? Even though in interviews with Cooke he seems to take a different position, that's the real central point to him taking that job -- no matter how good he is, that's all he can do. He can't go off with his own project fully formed from his own head. His own project is another person's work. So it's six of one.

MS: And it's not even like he's adapting Dostoyevsky, either. But, for a while anyway, Cooke was one of a few guys in mainstream comics who at least seemed to be setting a higher standard for himself than hacking out ripoffs of more inspired work. It's that Darwyn Cooke we get here: seemingly more interested in the generalities of the massive idea-farm that is mainstream comics than aping anyone in particular, playing around with tone and influence to work toward something entirely his own. He doesn't quite get there in these pages, and it seems now like he probably never will. But seeing him try here is pretty uniformly thrilling, even in the moments of outright failure. The successes are always more memorable.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Solo Is Not Necessarily The Best There Is At What He Does In New ‘Solo’ Series [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/09/Solo_1_Featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Everything We Can’t Wait To See At San Diego Comic Con, Part Two: Saturday & Sunday [SDCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/07/SDCC-Sat1.jpg?w=980&q=75)