Olympians: Superhero Bodies and What Real Athletes Look Like

There are certain phrases that have a special resonance for a Marvel kid like me. "Pocket dimension." "Lift (press)." "Marital status: unrevealed." This is the language of the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, and I used to pore over the pages of those little encyclopedias like I thought there was an exam coming. (I would have aced the Alien Races paper.) One phrase that came up a lot was "Olympic class athlete," used to describe characters with peak human abilities. For example, Nightcrawler is an Olympic-class acrobat, even though that's not a real thing unless you count opening ceremonies.

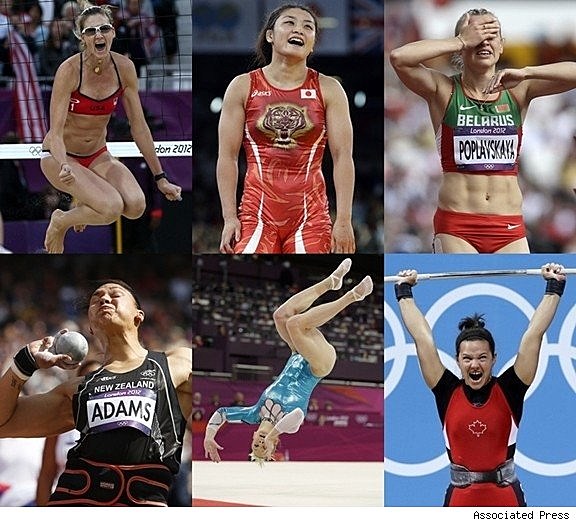

Thanks to the current games in London we're all getting a refresher on what Olympic athletes actually look like - and they look like a lot of very different people. They look like wrestlers, sprinters, fencers, weightlifters, boxers, shot-putters, rowers, marathon runners, judokas, pentathletes, swimmers, beach volleyball players, cyclists and a lot more besides. In fact, they seem a lot more varied than the characters in the pages of most super-books. So are superhero comics getting it wrong?

A couple of years ago Bongo Comics artist Nina Matsumoto posted scans to her blog from a book called The Athlete, by Beverly Ornstein and Howard Schatz. The scans show photos of athletes standing side-by-side in black underwear; some tall, some short, some wide, some narrow, some ripped, some skinny. Matsumoto headlined the post "athletic body diversity reference for artists." As with the current Olympics, the book shows that physically fit people come in a range of shapes and sizes - and by showing the athletes side-by-side and dressed alike, it communicates the idea concisely.

For a lot of comic artists these photos were eye-opening. Body diversity is a rarity in comics. There are exceptions - guys like Wolverine, Colossus, Nightcrawler and Beast stand out because uniqueness is part of the X-Men's core concept - but most members of the Justice League or the Avengers would be hard to tell apart in silhouette without their costumes. That's not necessarily an accident. Even when character design is meant to be distinctive, an artist's style will often take precedence. Uniformity can be an artist's hallmark.

But it would be generous to assume that uniformity is always a stylistic choice. Over-reliance on the same basic models seems to be a crutch for a lot of superhero artists.

I asked four comic artists who don't have this problem to help me with a simple exercise. Kalman Andrasofszky, cover artist for X-Treme X-Men; Ramón Pérez, recent Eisner winner for Tale of Sand; Jamie McKelvie, artist on Defenders; and Marcus To, artist on Batwing, all have a track record of making their characters look distinctive. I gave them a list of eight superheroes and asked them to rank them by size and match them to athletic body types to see if there was a consensus about what these superheroes should look like.

The heroes were Batman, Captain America, Flash, Namor, Nightwing, Spider-Man, Superman and Thor. All eight could conceivably be drawn on the same frame. So where did these artists place them on a scale from largest to smallest?

(The images shown here are illustrative for this article. The artists were not provided with any reference.)

Strikingly, Ramón Pérez and Jamie McKelvie gave exactly the same answers, while Marcus To flipped the order of only two characters, Flash and Nightwing. Kalman Andrasofszky looks like an outlier, but he only placed Namor and Spider-Man two places higher than everyone else. All four artists agree that Thor is bigger than Superman, Superman is bigger than Captain America, and Captain America is bigger than Batman. Nightwing, Flash and Spider-Man are all at the smaller end of the scale.

When it came to applying an athletic body type, the consensus among the artists was that Thor is a bodybuilder type. Pérez and To put Superman down as having an American football player's build, and McKelvie noted, "Logically, of course, Superman's power has nothing to do with his muscles, but I think an imposing frame on someone who doesn't use his power to oppress is part of his point."

Captain America is a boxer or a rugby player, though Andrasofszky suggested a marine's physique. All three types could be described as compactly muscular. Because Batman is an all-rounder, he was tagged as either a triathlete or a mixed martial artist. Namor, unsurprisingly, was labelled a swimmer-type by three artists, though Andrasofszky's ranking suggests a bulkier build. The character is more of a brawler than a speedster, so a water polo physique might fit.

Also unsurprisingly, three of four artists labelled Flash a sprinter, though Andrasofszky again dissented, suggesting he would be a speed skater; "little bitty guy up top with these massive, rippling thighs and calves." Nightwing is typically thought of as a gymnast, but real gymnasts are often shorter and broader than Dick Grayson, so Pérez tagged him as another swimmer and McKelvie classed him as a martial artist. As for Spider-Man; Andrasofszky said swimmer, McKelvie said gymnast - "but on the wiry side," To said "marathon runner," and Pérez said "nerd," which we're sorry to report is not a recognized Olympic discipline.

The four artists seemed close enough in their assessments to suggest that there's a clear understanding of how these characters should look, and they can't all be filed under a single superhero type.

So what about the women? The challenge to distinguish between silhouettes is arguably tougher for female superheroes, because their bodies are subject to a different kind of interest from the typical superhero reader. The female athletes competing at the London Olympics are a diverse bunch, but the women in a Victoria's Secret catalog are more likely to conform to type, and superwomen have traditionally been modelled more on the latter group than the former.

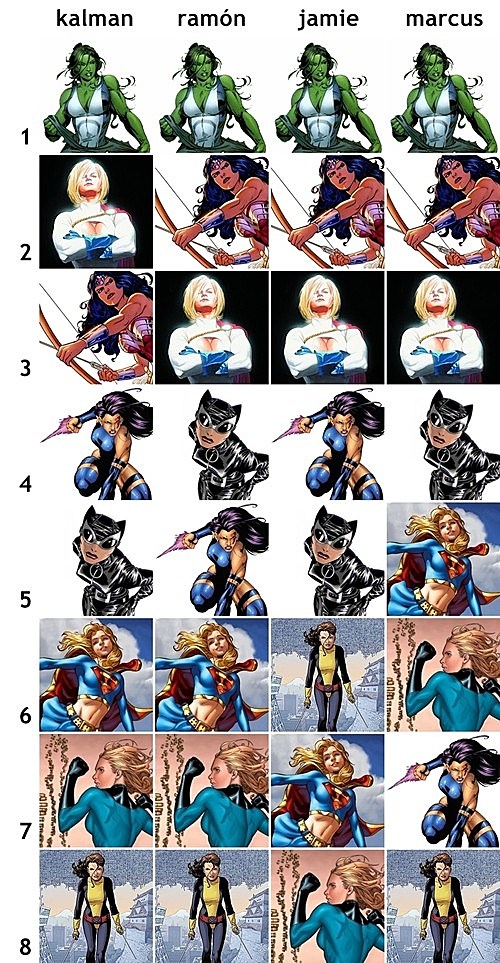

I asked the four artists to repeat the ranking exercise with eight female heroes; Catwoman, Invisible Woman, Power Girl, Psylocke, Shadowcat, She-Hulk, Supergirl and Wonder Woman. Here are the results:

With the women there's less clarity and less agreement. Everyone put She-Hulk first, but that seems like the gimme. Everyone put Wonder Woman and Power Girl in second and third, with only Kalman Andrasofszky reversing their order. After that it gets more scattered. Catwoman is either fourth or fifth. Psylocke is fourth, fifth or seventh. Supergirl is fifth, sixth or seventh. Sue Storm is sixth, seventh or last, though three of the artists agreed that Shadowcat is the smallest of the women.

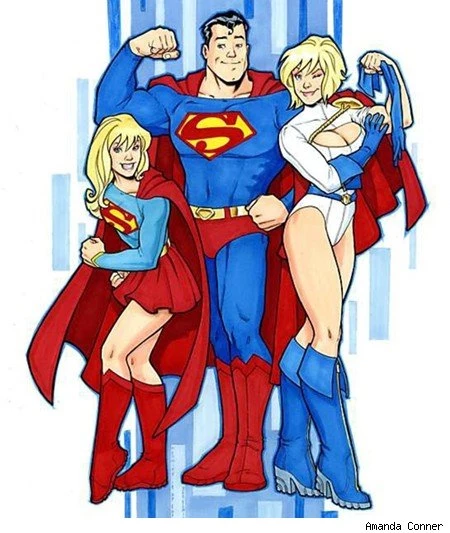

So what athletic types would the artists match these women to? Just like Thor, everyone saw She-Hulk as a bodybuilder. Andrasofszky put Power Girl and Wonder Woman in the same category but in a different weight class, and Jamie McKelvie said that Wonder Woman could do with "a bit more muscle" than she's usually shown with. Marcus To classed Wonder Woman as a mixed martial artist, while Ramón Pérez said she's an aerobic gymnast. Power Girl is a swimmer according to Pérez and a weightlifter according to McKelvie.

Psylocke is probably a martial artist, but Pérez suggested figure skater. Catwoman is probably a gymnast, but To offered cyclist. Andrasofszky thought that Supergirl would have bigger muscles than either Psylocke or Catwoman, but that her youth would make her smaller than either of them. Pérez thought she was a swimmer and To thought she was a basketball player. (I can't help but think of her as a tennis player, but that may just be because of the skirt.) Given that Power Girl and Supergirl are two versions of the same character, it's notable that only To placed them close together.

Invisible Woman and Shadowcat each come near the end of the list three times out of four, probably because they have non-contact powers. Marcus To had Sue Storm as a soccer player; McKelvie said she's "just generally in shape"; Andrasofszky categorized her as "MILF," which, again, is not a recognized sporting discipline. Shadowcat is a rhythmic gymnast by Pérez's reckoning; To described her as a roller derby jammer.

That there's less agreement on the women both in terms of ranking their size and determining their type suggests that the comic industry does not do a good job of distinguishing female body types. That's probably not news worth holding the front page for. Male heroes aren't always drawn distinctively, but the distinctions are widely understood. For female heroes there's less of a clear idea of what they're meant to be, because very few female characters look like She-Hulk or Shadowcat.

The Olympics show us an extraordinary range of female bodies, but even within the Olympics there has been controversy about what women "should" look like. Australian swimmer Leisel Jones was criticized by the media for her weight; American hurdler Lolo Jones was accused of looking too good; and weightlifter Zoe Smith was trolled for not looking good enough. Smith brilliantly hit back by writing "what makes you think we actually give a toss that you, personally, do not find us attractive?"

Clockwise from top left: Beach volleyball player, wrestler, sprinter, weightlifter, gymnast, shot-putter, all at the London 2012 Olympic Games.

Body criticism of Olympic athletes seems especially inane given that these athletes get the bodies they need for the sport they dedicate their lives to. They exercise to be good, not to look good, which makes them very different to actors and models who focus on what Details calls "vanity muscles" rather than work muscles.

Superheroes have the ultimate vanity muscles, because they never use their bodies at all; they only move in the minds of the reader. Superheroes exist to be seen, and their physiques are conjured from an inkwell. That may be why we've arrived at a uniform look that's based more on the men and women we see in ads, on TV and in movies than on the men and women we see on the track, on the court and in the water.

Fantasy and glamour is important to superhero fiction. As McKelvie noted, Superman's power has nothing to do with his physique. A lot of heroes are artificially enhanced by science, magic or mutation, including four of the women and six of the men on my lists. Superhero comics are not meant to be real. So does it matter that superheroes have diverse bodies?

All four of the artists I spoke to agree that it does, and they all gave the same reason; design speaks to character. As Pérez put it, "The body of a character, from musculature, to lack thereof, to posture, to gait ... tell us a lot about the individual. When defining characters I try to make them as unique as possible from head to toe."

Andrasofszky adds; "A character's physique tells as much about them as their face or their outfit." He acknowledges that "some fans prefer generic gorgeousness, and there's the concept Scott McCloud popularized, that the simpler and more iconic a character, the easier it is for anyone to identify with them," but for his own art he prefers to vary physiques.

"Superheroes are idealised, but there's not any one specific ideal, and I think they should reflect that," says McKelvie. Adds To, "If everyone looked the same I don't think it would be as visually appealing to the eye.

Superhero characters are products of design. If design matters, there should be some consistency in a character's look from one artist to the next - and some inconsistency between characters from a single artist. It should matter that She-Hulk is big and Shadowcat is slender. It should matter that Superman is bigger than Batman. It should matter that Power Girl doesn't look like Supergirl, and it should matter that Spider-Man won't be confused for Captain America in the dark. If design matters, if character matters, then diversity matters. Superheroes shouldn't have to look like Olympians, but they should look as diverse as Olympians do.

More From ComicsAlliance