Ask Chris #141: How ‘Super Mario Bros.’ Works

Over a lifetime of reading comics, Senior Writer Chris Sims has developed an inexhaustible arsenal of facts and opinions. That's why, each and every week, we turn to you to put his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

Q: What's the deal with the Super Mario family of video games? Which of the games "actually" happened? -- @pbarb

A: If you don't follow me on Twitter, then you missed a moment earlier this week where I chugged an extra-large coffee and decided that it was time to figure out how the timeline of the Mario games worked. Well... maybe "missed" is the wrong word, but that's definitely a thing that happened. To be honest, I've never really worried too much about whether or not the plots of the Mario games make sense. As much as I love those games, storytelling isn't exactly their primary concern, and in terms of plot, they tend to limit themselves to "run left to right; save princess." The thing is, though, there's just enough there that makes them difficult to figure out.

To be honest, I've never really worried too much about whether or not the plots of the Mario games make sense. As much as I love those games, storytelling isn't exactly their primary concern, and in terms of plot, they tend to limit themselves to "run left to right; save princess." The thing is, though, there's just enough there that makes them difficult to figure out.

We'll start with the basics, and the first obvious sticking point here is Super Mario Bros. 2. It's a pretty well-known piece of pop culture trivia so bear with me for a second, but the sequel to Super Mario Bros. that we got here in America wasn't intended to be Mario 2 at all. The original Mario 2 was basically just a handful of extra levels using the same engine and graphics as the first game, but designed to be a lot more difficult in order to give players a new challenge. The problem -- at least as far as Nintendo of America was concerned -- was that it ended up being way too difficult for American audiences, and as a result, it wasn't released over here until 1993 as The Lost Levels.

Still, Super Mario Bros. was so ridiculously popular that it kind of needed some sort of sequel, so they took a game called Doki Doki Panic (which had itself originally started out as a prototype for a vertically scrolling Mario game) and changed the graphics around so that instead of a family of festival mascots, it was Mario and his pals. The thing is, the gameplay was so different from Super Mario Bros. -- with a new emphasis on picking up enemies and digging vegetables out of the ground to use as weapons, levels that could scroll to the left or the right and different abilities for each character -- that it just felt weird. It needed some kind of justification, and the solution they came up with was that in the end, it was all a dream.

It ain't exactly Mass Effect.

The second sticking point is Mario 3, and you've probably heard this one, too, since it's one of those "blow your mind" fan-theories that floats around the Internet. At the beginning of the game, a curtain goes up, and you can see the shadows of bushes and clouds against the background:

In the game itself, platforms are screwed into place or held up on wires, and the end of a stage comes when you literally walk to the left where there's a different backdrop. The conclusion: Super Mario Bros. 3 is a play. It's a stage performance and none of it is "real" -- which brings us back to the whole "aren't they all imaginary stories?" question, but again, bear with me.

Quick aside: As weird as it might sound, this isn't actually all that weird for an NES game. The first Castlevania, for instance, ends with a pun-filled credit sequence listing all of the "actors" playing the parts of the monsters, but nobody really goes around explaining how the increasingly complex continuity of a bunch of dudes destined to eternally smack Dracula around with a whip is actually meant to represent a metafictional horror movie franchise. Of course, with Castlevania, "Christopher Bee as Dracula" did not become a recurring gag.

So if Mario 2 is a dream and Mario 3 is a play, where does that leave the rest of the games? And what about the Paper Mario series, which are all presented as storybooks, and sometimes as storybooks within storybooks? And even if you get all that straight, how come these guys who are literally trying to murder each other most of the time invite each other over for party games and go-karting? It's a tough nut to crack, but I think I've figured it out.

First of all, Super Mario Bros. definitely happens. I don't think there's any disputing that. However, it's not the first to happen chronologically. That honor goes to Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island, which takes place when Mario is an incredibly annoying little diaper baby:

This is important for a couple of reasons, namely that it explains why Mario and Yoshi are instantly bros when Yoshi shows up in Mario World. If Yoshi was willing to put up with Mario even when the player was trying to figure out how to chuck him into lava, then they have a connection that goes far beyond the average plumber and pet dinosaur. More importantly, it introduces Shyguys into the regular Mario continuity in a way that traumatizes Mario as a baby. Grim as that might sound, it'll be important later.

So: Yoshi's Island happens, then years later, SMB1. Peach gets kidnapped and taken to various castles, Mario runs to the right, throws Bowser into lava a couple of times and saves the day. Then he comes home, goes to sleep, and then has this bizarre dream where he's working through the stress of what he just did. That's what SMB2 is: Mario subconsciously dealing with all of his hopes and fears from the previous game.

In a lot of ways, Mario 2 represents an ideal world for Mario. He's not alone on his mission -- Peach is there beside him, and so's Luigi, who's no longer just a palette swap, but a distinct person with his own abilities. Anybody who subscribes to the theory that Mario looks down on his brother just needs to take a look at this game and realize that Mario, a character quite literally defined by his ability to jump, sees Luigi as someone who can jump even higher. Even Toad, who's a constant source of frustration in SMB1, is now a valuable part of the team.

The whole game obeys a weird kind of dream logic, too, full of nightmare monsters like Phanto (that creepy mask that would chase you when you picked up a key), potions that create doors to shadowy mirror worlds, and even a "you were there, but different" version of Bowser in the form of King Wart. The key, though, is the Shyguys. They're the villains in Mario's nightmares because they were the things that scared him when he was a kid -- you could even argue that creepy-ass Phanto is just Baby Mario's exaggerated memory of the Shyguys' masks.

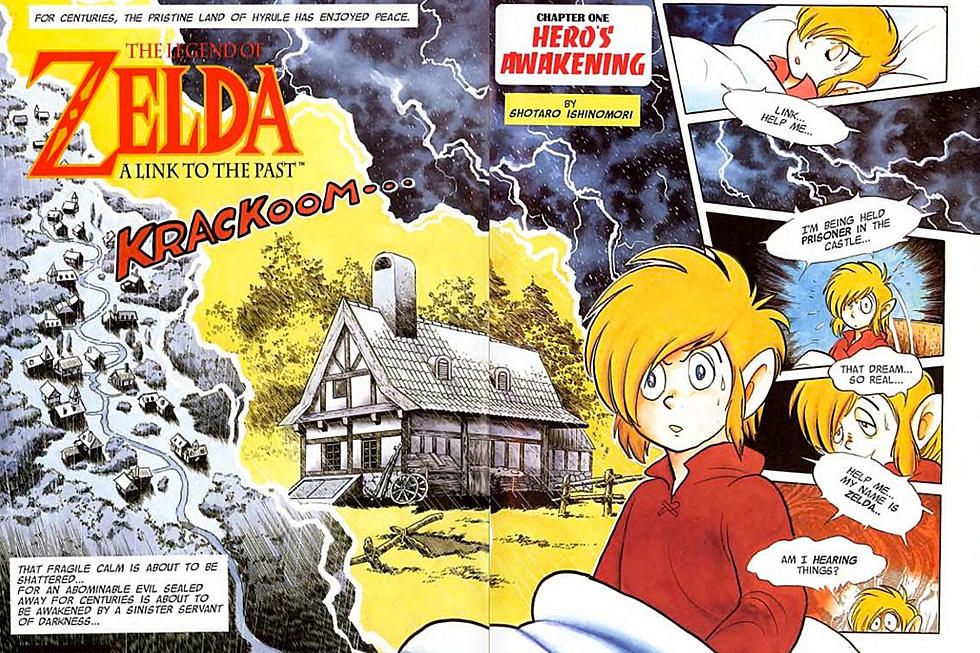

It's worth noting that the idea that Mario 2 is influenced by Mario working through his childhood fears and memories is actually supported by the (non-canonical?) comics that ran in Nintendo Power, where it was revealed that as a kid, Mario would often go out and pick vegetables from a garden:

One of the other elements of Mario 2 is that it also features a curtain pretty prominently on the Character Select screen. Why? Because Mario's already thinking of the play that will become Mario 3.

This actually makes a whole lot of sense, when you consider that a) Princess Peach has her own loyal, adoring subjects in the Toads, and b) their crowned monarch being kidnapped by a fire-breathing dragon monster and then rescued by a plumber is probably the most exciting thing to happen in the Mushroom Kingdom in a long time. It's natural that this is a story that the Toads would be telling each other, and that they'd want to hear more of, and since the Mushroom Kingdom doesn't seem to have a whole lot of movie theaters, turning that epic adventure into a play seems like a natural fit. They just need to make it a little more exciting for the stage.

When you get right down to it, that's really what Mario 3 is: The same basic story of Mario 1 (run to the right, save princess), but embellished and expanded so that it's a little less repetitive. You can see the Toad director and screenwriter giving each other a sidelong glance as Mario casually explained "So then I went to the SEVENTH castle and she wasn't THERE, either," and deciding that what this story really needed was some airships. So they threw some in, thought up a few exotic locations with more visual appeal, gave Bowser some plucky henchmen and turned the Princess's kidnapping into a third-act plot twist.

Obviously, in order to make things exciting and (sort of) accurate, they got actual monsters to play the monsters, and got Bowser to play himself, giving him a climactic battle scene that was way more exciting than the original. That leads to the question of why they'd bother hanging out with the guy who just kidnapped their princess (let alone play soccer and go golfing with him), and I think that's as simple as the Mushroom Kingdom operating on the same kind of logic that Warner Bros. cartoons do. You know Sam and Ralph, the sheep dog and the wolf who clock in each morning and try to kill each other 'til the work day's over? That's Bowser and Mario. Dude's just got a job to do, and that job happens to be kidnapping princesses.

That would seem to hold up in Super Mario RPG, where Mario, Peach and Bowser all team up to save the Mushroom Kingdom from an outside threat, which fits neatly into continuity between World and 64. From there on out, everything's pretty straightforward.

It just sometimes happens in space.

That's all we have for this week, but if you've got a question you'd like to see Chris tackle in a future column, just send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #AskChris, or send an email to chris@comicsalliance.com with [Ask Chris] in the subject line!

More From ComicsAlliance