![Bryan Lee O’Malley Talks ‘Monkey Manga’ with the Men Who Influenced ‘Scott Pilgrim’ [Exclusive]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2011/07/omalley-manga-2.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Bryan Lee O’Malley Talks ‘Monkey Manga’ with the Men Who Influenced ‘Scott Pilgrim’ [Exclusive]

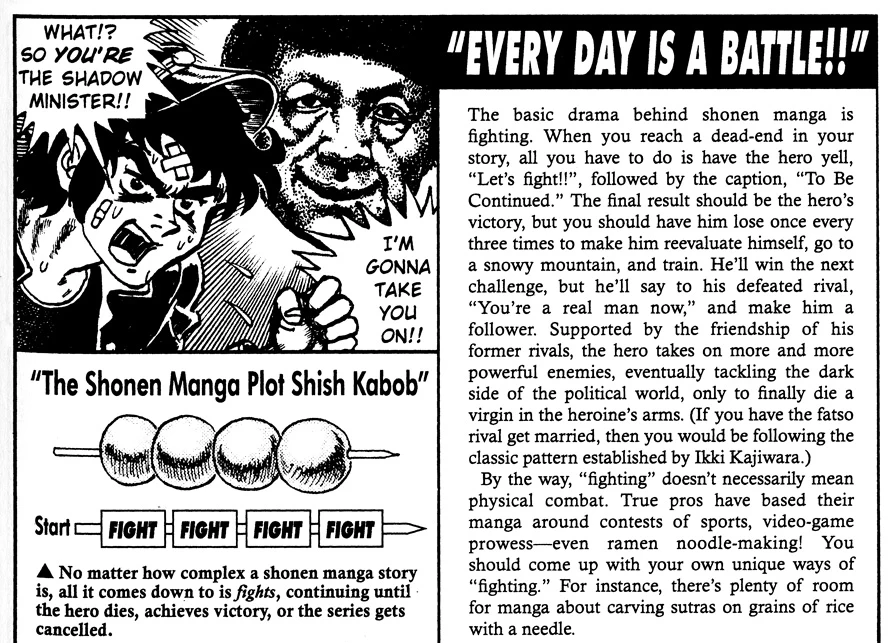

Back in 2002, long before Bryan Lee O'Malley had written and illustrated a New York Times best-selling graphic novel series that would later be adapted into a major motion picture, he was an aspiring creator who wanted to learn more about shonen manga. That's when came across a book called Even a Monkey Can Draw Manga, a satirical series by Kentaro Takekuma and Koji Aihara that parodied both the conventions of mainstream manga and the Japanese comic book industry itself.

For O'Malley, whose Scott Pilgrim series would later be renowned for its fusion of North American and Japanese comic book styles, the book was nothing short of inspirational. Today, ComicsAlliance is pleased to feature an exclusive conversation between the three men that discusses the differences between the American and Japanese comic book industries, why nerd characters in Western comics can still have sex, and why O'Malley would like to try his hand at working on a Japanese comics series.

Bryan Lee O'Malley: Bryan Lee O'Malley, age 32, Canadian, professional cartoonist and creator of Scott Pilgrim.

Kentaro

Takekuma: My name is Kentaro

Takekuma, I am one of the creators of Even a Monkey Can Draw Manga. I am 50. Pleased to meet you.

Koji

Aihara: Hello, I'm Koji

Aihara, 47 years old, manga artist. I am one of the creators of Monkey Manga. Pleased to meet you.

Knall: Bryan, let us know how you came to read Monkey Manga.

O'Malley: Well, I think it was published in America by Viz around the end of 2002. My roommate at the time was the manager of a comic store and he brought it home. I was working on my first solo book, Lost at Sea, and planning ideas for Scott Pilgrim, so I found your book at the right time. I remember reading the second chapter about inking panel borders with a ruler and laughing so hard, because I recognized the situation. It was the first time I saw the life of a comic artist reflected back at me.

Knall: Was there anything that you felt was different from how you had been approaching your work, or how American comics artists were working?

O'Malley: I had been fascinated by Japanese comics since I was in high school, but at that time (late 1990s) there wasn't really a lot of material in English. So even though I was planning a "shonen"-style comic in Scott Pilgrim, I really hadn't read a lot of shonen comics. Ranma 1/2 was the only one I knew well. Even though I knew Monkey Manga was satirical, I saw that it could be a real guide to the Japanese comic industry. In America, the comic industry is mainly costumed superheroes, which is something I never had much interest in. In general, the wide exploration of genres in Monkey Manga was inspirational to me, even if you (Takekuma & Aihara) were joking around.

Takekuma: We started publishing Monkey Manga in Shogakukan's Big Spirits Comics in 1989. At the time, it was the third best selling weekly Manga magazine in Japan. Japan already had a history of 50 years of story manga, and it had developed into a major industry.

Aihara: I drew everything as a gag. I tried to emulate all the stereotypes in Japanese manga, and portrayed them through parody. I'm relieved to hear that you got the joke.

Takekuma: At the time that me and Aihara Koji started Monkey Manga, the industry had already developed into big business, and was looking for manga that would make money instead of new forms of expression. So while they were selling well, I felt that these books were starting to lose the spirit and passion that characterized the manga we had read as children. I aimed to pick up "patterns" that had started to develop in well-selling manga, and parodized them.

O'Malley: In 2002, translated manga wasn't a big business in America, so I think some editors were able to bring smart work in under the radar. I remember reading Taiyo Matsumoto's Black and White and some Usamaru Furuya stories around the same time as Monkey Manga. It seems like, if anything, the manga industry has become more business oriented in the past 20 years. I still enjoy plenty of new manga, but it tends to be very slick and has a corporate feeling -- the artwork doesn't look like it could be done by one person. I couldn't imagine drawing something like Death Note or 20th Century Boys, whereas the work of the 1970s and 1980s feels more approachable, i.e. Rumiko Takahashi or Mitsuru Adachi.

Takekuma: In Japan, weekly magazines have been the standard publication medium for manga for a long time. So for manga that have an intricate story or setting, it is vital to have the help of an editor or assistants for the weekly publication. Ever since Katsuhiro Otomo became popular in the '80s, more and more mainstream manga started to have really stiff art. One of our aims with Monkey Manga was to point out the problem with major manga becoming more and more business-oriented and less pure. However, we were extremely lucky to be able to publish in a magazine like Big Spirits, which was selling over 1 million copies per issue. Aihara had been a very successful artist before Monkey Manga so that helped us get that chance.

Aihara: Bryan, do you create your comics all by yourself?

O'Malley: I created most of the Scott Pilgrim series by myself. Only on the final book was I was able to hire 2 assistants. I think it's probably pretty obvious to another artist reading the book -- the backgrounds suddenly become much more detailed. Most fans don't seem to notice the change.

Aihara: I very much liked [in Scott Pilgrim] how the entire page was filled with your style and ideas. In Japan, there are very few artists working that way anymore.

Aihara: I very much liked [in Scott Pilgrim] how the entire page was filled with your style and ideas. In Japan, there are very few artists working that way anymore.

O'Malley: We don't have the same infrastructure for comics here. The industry developed very differently here than in Japan. In America we don't really have a system for story editors, or assistants, or any form of monthly/weekly comic magazines. I've spent a lot of time feeling frustrated about that. The whole history of comics in America has been about Marvel & DC superhero characters. New stories and ideas have been in underground or independent comics. I'm generalizing, but that's certainly how it feels to me. I never thought I could have success with my books to the point where I would sell a million copies and have a movie adaptation. It was astronomically unlikely. I would have expected to sell maybe 1000 copies.

Takekuma: When I read Scott Pilgrim, I felt that in the beginning, it has a very different structure and style than Japanese manga. However once you reach the battle scenes, it feels very much like a Japanese manga, especially in how you structured the panels. It develops into a very strange, neither American nor Japanese atmosphere.

Aihara: I did feel the inspiration from Japanese manga, but it did not strike me as a ripoff of manga style, but a very unique way of expression, I found it a very interesting work. I appreciated you using your own style of expression. Also, I thought your use of solid blacks was very skilled and attractive.

O'Malley: Yeah, I really wanted to create a hybrid. I wanted to reach towards the japanese comics from my own starting point. When I was younger, I slavishly copied the "look" of manga and anime, but I never thought about the underlying form much. There are so many things that make Japanese comics feel like Japanese comics -- it's just a different approach to storytelling. I'm not Japanese, so I'll obviously never make "Japanese comics" myself, but I'm still learning a lot from manga and I think that education will continue for a long time.

Takekuma: I found the depiction of student life very interesting because it was so different from Japanese students' experiences. Scott is pretty much a nerd, but he still experiences romance and has sex. Japanese romantic comedy manga depicting the life and love of a nerd never depict relationships with several women. Adult-only erotic comics being the exception of course.

O'Malley: Oh, yeah, I had an interview with a Japanese reporter recently and he mentioned the same thing (re: nerds being "virginal"). I thought that was very interesting! It's a cultural difference that I never realized.

O'Malley: Oh, yeah, I had an interview with a Japanese reporter recently and he mentioned the same thing (re: nerds being "virginal"). I thought that was very interesting! It's a cultural difference that I never realized.

Takekuma: As an addition to the above, there is a genre in Japanese romantic comedy called "harem stories". These depict a nerdish guy being approached by several women, escalating into a harem situation. Scott on the other hand, while being kind of a nerd, has his own personality, plays in a band, and gets serious about dating. There are a few things influenced by Japanese stories, but I thought the depiction of romance was unique in a way that is very rarely seen Japan.

O'Malley: Scott Pilgrim took some inspiration from "harem" manga (like Ranma 1/2). But I guess he's an incongruous character type to be the hero of the story. On the other hand, I often find myself frustrated with the hero in a manga story. The boy is always timid. I'm pretty shy myself, as I'm sure most cartoonists are, but I guess in America we like to see our heroes take action, especially with regards to women.

Takekuma: In both the books and the movie, Scott has this cute girlfriend in Knives, but dumps her at the first chance he gets after he meets Ramona. In Japan, your editor would probably stop you from writing that. They would say readers would side with Knives, and your hero looks like an ass.

O'Malley: Hmm, I think that's a bad storytelling habit of mine. However, I should point out that Scott Pilgrim's Precious Little Life was initially published as a 160-page book, so readers were introduced to both Knives and Ramona during their first experience of the story. Maybe if the first chapters were serialized in a magazine, the dismissal of Knives would be more of a problem for readers. During the gaps between serialization, readers' imagination can go wild.

Takekuma: I found it interesting that Scott doesn't really have a "reason" for dumping Knives. If it was published in a Japanese magazine, the editor would press you for a reason why he HAD to break up with her. For example, if Knives had a really horrible hidden personality, and Scott found out about it, together with the readers. In Scott Pilgrim, there was no build up like this, so I was a bit surprised, but at the same time it was a very fresh experience for me.

Aihara: What kind of tools do you use for your work? Brushes?

O'Malley: Yes, I use mostly brushes, a #2 or #3 brush. The screentone is mostly done via computer. It's hard to find screentone here. I don't know if Japanese artists mostly use "real" tone or if they use computers now as well.

Takekuma: A lot of the younger artists nowadays use computers to finish up their work. Monkey Manga was 100% analog. Neither I nor Aihara had a PC at the time. I bought one when we wrapped it up.

Aihara: I am a very analogue person, so I still use stick-on tones, but I think people using computers for this are increasing. Not even that, some artists are doing the entire process on the computer and sending their editors only the files!

O'Malley: It's a different world over here, but I don't think I've ever handed my editor a physical page! Of course, my publisher was on the other side of the country.

Aihara: Have you ever considered publishing in a Japanese serial?

O'Malley: You know, I've always been fascinated by the Japanese editorial process for comics. One day, if I get the chance, I would definitely be curious to work with a Japanese editor. As I said earlier, we don't really have anything like that here. I had hardly any story editing on Scott Pilgrim. As the story went on and became more complex, I really started to wish I had a seasoned editor to help me out. I think I could have made a much stronger series that way.

Takekuma: Monkey Manga is originally 3 volumes, and currently collected in a new edition of 2 volumes. Only two thirds of volume 1 were translated into English. I would love to be able to be able to have American and Canadian readers read the complete work. If we ever get the chance, I would be delighted to meet and talk in person.

O'Malley: Yes, I really want to come to Japan sometime -- I've never been.

Aihara: Thanks for talking with us today. It was a lot of fun.

O'Malley: Thank you both! It was an honor!

Takekuma: Thank you, let's meet up some time.

[Translated and moderated by Philipp Knall]

More From ComicsAlliance

![All The Exclusive Art Prints To Check Out This Weekend At San Diego Comic Con [SDCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/07/Prints-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![Bryan Lee O’Malley Announces ‘Worst World’, A New Trilogy Of Graphic Novels [SDCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/07/Worst-World-Featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Everything We Can’t Wait To See At San Diego Comic Con, Part Two: Saturday & Sunday [SDCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/07/SDCC-Sat1.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Mondo Gets it Together for its New Ramona Flowers Figure [Exclusive]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/06/mondo-ramona.jpg?w=980&q=75)