Why Marvel Owes No Apologies for Captain America’s ‘Tea Party’

It was so much easier when Captain America could just punch prominent Nazis.

Ed Brubaker and Marvel Comics recently came under fire by Fox News due to the characterization of a small town protest group in Captain America #602. In the issue, Bucky and the Falcon, tracking down the faux 1950's Captain America, find themselves in rural Idaho at the center of a gathering anti-government storm. And here Brubaker's troubles begin.

Due to what's been deemed both a lettering error and an editorial oversight, a sign that read "Tea Bag the Liberals Before They Tea Bag You" appeared at an anti-tax rally within the story, and a controversy erupted when a conservative blogger supportive of the Tea Party caught wind of it several weeks later and accused Marvel of "making patriotic Americans into your newest super villains."

Due to what's been deemed both a lettering error and an editorial oversight, a sign that read "Tea Bag the Liberals Before They Tea Bag You" appeared at an anti-tax rally within the story, and a controversy erupted when a conservative blogger supportive of the Tea Party caught wind of it several weeks later and accused Marvel of "making patriotic Americans into your newest super villains."

Marvel responded in an interview with CBR, where Joe Quesada insisted the sign was an accident, and promised that the offending image would be stripped from all future reprints of the story. The controversy and subsequent reversal was soon picked up by one of the cogs in the cyclonic perpetual emotion machine that is Fox News, who scored Marvel's apology as a win for righteous conservatism over the oppressive liberal media.

It shouldn't be entirely surprising that Marvel, now a multi-billion dollar subsidiary of Disney, would kowtow to the media behemoth that is Fox News. Marvel Comics are for people of all stripes and creeds, of course, and no one should be made to feel unwelcome for leaning one way or another politically. Brubaker, however, has established himself as the preeminent Captain America writer by deftly weaving modern real-world allegory with bombastic superheroics to powerful effect, and so there was something rather disingenuous about Marvel's recant, as it seems to be missing the point; sure, you can remove the "Tea Bag the Libs Before They Tea Bag You," sign, but are you really saying this story isn't about the Tea Party movement? Isn't that what makes the story so interesting?The intermingling of real-world concerns with colorful theatrics has been huge factor in the success of Ed Brubaker's Captain America run. From its earliest installments, there have been seeds of the real world planted throughout this celebrated tenure, and that has been the lens through which we understand who Captain America is, and how he functions as a national hero.

Take, for example, the villainous character of Aleksander Lukin. Introduced in the writer's first issue, Lukin is a Cold War holdover, born to the fires of WWII. These traits are somewhat commonplace to Captain America adversaries, but what sets Lukin apart is his role as the chief executive of the powerful and far-reaching Kronas Corporation.

Lukin's Kronas Corporation was all the worst parts of big business, with shadowy holdings, international immunities, and even their own energy company subsidiary, Roxxon. Lukin standing at the head of this powerhouse made him a new kind of villain, one who seemed to arise from the front of real-life newspaper pages. Lukin, Kronas, and Roxxon all seemed to echo the dangers and fears gripping the nation in the wake of the Enron scandal, Halliburton and the growing 21st century military industrial complex.

Despite how it may appear, these stories were not strictly about vilifying corporations, or creating stories about "Captain America vs. Corporate America." Instead, what made these stories powerful was their unique ability to achieve resonance with the audience. The stories didn't take pause to qualify that "these companies are good, and these ones are bad." Instead, they drew from real world headlines, and extrapolated the broader lessons the nation had learned. This is an important detail in the balance of using the real world to enhance fiction-- that it is less effective to ground things in hard fact than it is to construct them so that they create the same sensation, and provoke the same emotional reaction as the real world.

In a sense, all of Brubaker's Captain America can be read with that same search for emotional American resonance. Steve Rogers' commitment to saving and redeeming his fallen partner, the Winter Soldier, can be interpreted as a metaphor for America's responsibility to it's troubled veterans. The Philadelphia bombing could be read as a take on an act of domestic terror. The addle-minded 1950's Captain America, who struggles to recapture a long-lost and possibly-never-existed sense of who he is and what America is meant to be, can be read as a take on certain politicians' brazen tactics of imagining a "Real America" of traditional ideals with which the presumably "un-Real America" has lost touch.

In a sense, all of Brubaker's Captain America can be read with that same search for emotional American resonance. Steve Rogers' commitment to saving and redeeming his fallen partner, the Winter Soldier, can be interpreted as a metaphor for America's responsibility to it's troubled veterans. The Philadelphia bombing could be read as a take on an act of domestic terror. The addle-minded 1950's Captain America, who struggles to recapture a long-lost and possibly-never-existed sense of who he is and what America is meant to be, can be read as a take on certain politicians' brazen tactics of imagining a "Real America" of traditional ideals with which the presumably "un-Real America" has lost touch.

Of course, none of this is to say that these are the ways that the stories have to be read; they are merely offered layers that are available to be appreciated. As structurally sound fiction, all of these stories can be read and enjoyed for their simple, literal face value. Still, it is their allegorical subtleties that provide the deep richness that has won the book its critical acclaim.

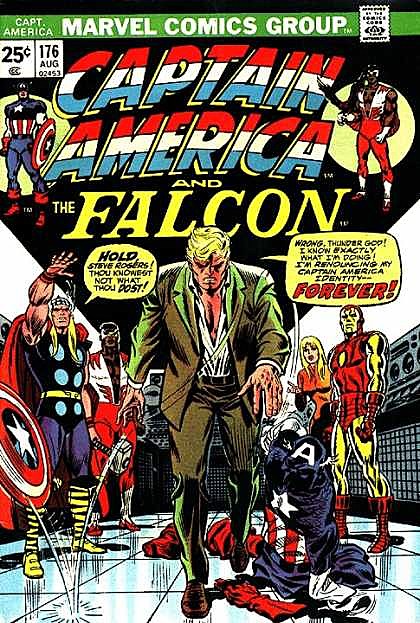

Nor is Brubaker the first Captain America caretaker to use real-world circumstances to cement the character as a barometer of the national mood. Most notably, it was during Steve Englehart's celebrated Secret Empire storyline in 1974 that Cap became so disillusioned with betrayals at the highest levels of government that he forswore his cowled identity.

The story ran contemporaneously to the Nixon/ Watergate investigations, and Steve Rogers' disenchantment with the American ideal was meant to reflect that of many Americans who felt betrayed by their government. Of course, had there been an Internet in 1974, there would have likely been some C.R.E.E.P. backers that would have lamented the yesteryears when Silver Age heroes knew to only tell us to trust all figures of authority, and thus keep us in our place in the world. But I digress...

This all goes a long way to take us back to Cap #602, and its kinda-sorta Tea Partiers. It seems totally obstinate to pretend that last year's Tea Party uprising, and even 2008 Anti-Obama rallies, had no bearing on this story. The general sense of outrage, and the anti-government, anti-taxes platform was just as ripped from the headlines as was Kronas.

And the same must be said for the racial components of Bucky and the Falcon's visit to small-town America, where the Falcon -- a black hero -- remarks at the heated faux-Tea Party rally that "I don't exactly see a black man from Harlem fitting in with a bunch of angry white folks." Because whether Warner Todd Houston likes it or not, anyone with a pair of eyes will tell you that there is a strong tinge of racial tension present in at least some of these rallies, whose leader Mark Williams once called Obama "an Indonesian Muslim turned welfare thug and a racist in chief."

Brubaker is not deriding all those who rally peaceably, but rather taking the boiled down, shorthand version of this controversy, and using it as a storytelling tool. Ultimately, whether this book is sanctioned by the for-profit Tea Party Convention or not, it addresses the pitfalls of the mob mentality, along with the dangers of rural xenophobia, which the Tea Party must address if it is going to grow into a viable national voice that can be taken seriously by serious-minded people. If not, it will remain a cartoonish caricature ripe for parody.

It also is vital to remember that Brubaker's personal politics, while they might inform his work, are also wholly separate from it. This seems especially pertinent when the FoxNews.com piece cites Brubaker's Twitter posts with regards to certain prominent conservatives like President George W. Bush, Sarah Palin, and Michelle Bachman, as if the writer's feelings on them are somehow proof positive as to some subversive agenda on his part.

It also is vital to remember that Brubaker's personal politics, while they might inform his work, are also wholly separate from it. This seems especially pertinent when the FoxNews.com piece cites Brubaker's Twitter posts with regards to certain prominent conservatives like President George W. Bush, Sarah Palin, and Michelle Bachman, as if the writer's feelings on them are somehow proof positive as to some subversive agenda on his part.

These personal views certainly inform the work, and help shape the perspective the author brings to his assignment, but it is a far leap to assume he has converted Captain America into his own personal soapbox, (that's what "Green Arrow" is for). To insinuate that he would do so is an assault on the integrity of both the writer and the editor. If anything, he should be lauded for actually taking a book that is about a character that represents the ideals of America, and introducing, through conflict, issues that actually pertain to American life.

It may not play in every corner of the country, but for a company that makes its bread telling tales of heroic ideals, standing up for something might be just the kind of great responsibility that goes with their great power.

More From ComicsAlliance