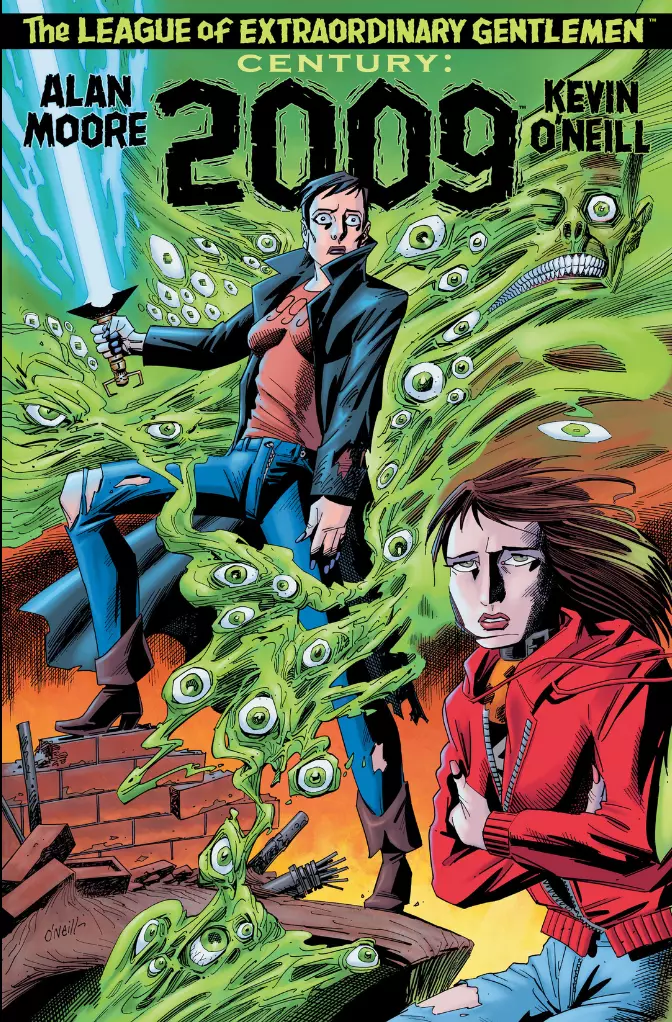

![Four Micro-Essays on League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: 2009 [Review]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2012/07/lxg-kevinoneill-cover-top.png?w=980&q=75)

Four Micro-Essays on League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: 2009 [Review]

Kevin O'Neill and Alan Moore's League of Extraordinary Gentlemen was one of those books that was waiting for me when I came back to comics after high school. Two trades full of familiar and unfamiliar characters having adventures. I liked it, though maybe more for the spectacle than the craft. Now, years later, another chapter of LoEG has come to an end in the form of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century: 2009, and I find myself in the opposite position. I'm not too impressed with the story as it rolled out, but it was told in such a skillful way that I can't help but be pleased with the ultimate product. Click through for four examinations of things that Moore & O'Neill did both well and poorly in LoEG: 2009. Spoilers follow, if you've somehow managed to miss the press blitz on 2009.

The Century books, 1910, 1969, and 2009 are 80 pages each. That isn't too long, about the length of four regular comics each and a fat graphic novel when taken all together. It feels longer, though. Even setting aside the text pieces, which close out every volume, these stories take a while to read. You can't burn through these comics like you can with normal floppies or even a full trade. You have to sit and take it in at its own pace.

Part of that is undoubtedly due to Kevin O'Neill sticking close to a three-tiered, eight or nine panel grid for the vast majority of 2009. It lends the book a density that does wonders for the mood of the book. A lot of things are going on in this issue -- sea-based terrorism, cultural malaise, a prophesied Antichrist -- and O'Neill absolutely sells the idea that everything is coming to a head. Even the breathers, the moments when people pause or eat or shower, feel claustrophobic and fraught with looming danger.

Moore and O'Neill spend twenty panels across four pages on Orlando, a legendary immortal warrior who regularly changes from male to female and back again, walking home from the store, taking a shower, getting her period, and eating. There's no plot-centric forward motion to speak of, no big reveals, but it works. It's a character-building and world-building sequence, and none of it feels like wasted time or vamping. It forces you into accepting the pace of the series and buying into its world. That pace is staccato and undeniable, like a juggernaut. The hits keep coming in rapid succession, and the narrow window we have into the world of 2009 gives us just a small slice of the picture.

O'Neill mixes it up between nine and eight panel grids. Occasionally, instead of having three panels to a tier, he'll use just one panel for a broader shot, or combine two tiers into one larger panel. These moments feel bigger than everything else in the book, and are often silent. It's the closest you come to a break in the pace, but these larger panels are far from comfortable. They're like the sharp intake of breath before an accident, or a ball paused at the top of a hill before rolling down. Once these panels pass, we get right back to the horror. The wider panels serve to re-emphasize the hectic pace and density of 2009.

And sometimes, when O'Neill draws the panel borders so that they expand and warp under the effect of the hallucinogens the characters are using or crack and bend under the weight of monstrous evil, the structure of the book moves from a scaffolding that the story is hung on to part of the story itself. Reality and fiction blurs right before our eyes.

2009 is, at least ostensibly, an adventure comic, like Amazing Spider-Man or Action Comics. We have a colorful cast of characters with quirks and powers, and they're going up against a big evil bad guy. What's different about Century in general and 2009 specifically is that Moore and O'Neill are far from kind to troupes of heroes.

In 1910, the heroes accidentally give the idea to create an Antichrist to the bad guys. In 1969, the heroes attempt to solve the puzzle of the Antichrist and find themselves not only too early -- the Antichrist plan had been backburnered after the events of Rosemary's Baby -- but utterly fail in their mission and collapse under pressure. Mina is abused, driven insane thanks to a bad trip on an LSD-alike, and committed to a mental institution. In her absence, Orlando and Allan Quatermain completely collapse. Quatermain relapses and becomes addicted to heroin, and Orlando goes off to join the army. The heroes prevented a bad guy from gaining access to massive power by sheer accident, but that prevention resulted in the bad guy actually getting to create his little Antichrist at a later date. In 1969, the heroes lose.

Originally, the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen were more of a covert team. They acted behind the scenes to save the day. In the 20th century, they just don't have what it takes. 2009 is littered with references to that effect. The setting is hardly the shining utopia that anyone expected. There's a strong undercurrent of lost hope and rampant fear running throughout the background of 2009. At one point, Mina remarks that the London of 2009 "looks Victorian." The world has regressed to the mood of Mina's unbelievably strict and awful time period.

On top of that, Quatermain is homeless. Quatermain is an archetypal hero, a big game hunter and an adventurer in a classic mold. When he meets Orlando again after some time apart, he rejects his history and aptitude for adventure. "I don't do all that stuff any more. I--I can't. Leave me alone!" he says. He refuses to take part in the very thing he was created for: adventure.

Still later, Moore makes the subtext plain. "That's all ****! All the adventuring... th-that's what ****ed us all up, isn't it?" Quatermain says. "I--I could have just been a traveller. You could have taught music. But no. We always have to be the heroes, don't we?" Being a hero has led Quatermain, and the rest of the cast, into a life of horror and misery.

It's a cold point, but an interesting avenue for telling an adventure story. Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns is about a man getting his groove back by embracing his heroic nature. 2009, and by extension the rest of Century, is about heroes who are slowly beginning to realize how terrible fighting forever is. There are no happy endings for a hero. You don't get to walk off into the sunset with your loved ones. You have to stick around, you have to fight, and you have to sacrifice everything you ever had in the name of good. Even Quatermain's opiate addiction returned. He says that he couldn't stay clean. "Not forever."

At one point, Orlando offers Emma Peel immortality. Normally, we see immortality as a gift, a gateway to adventure. Peel freezes and stares at Orlando. "Oh God," she says. "Y-you are an absolutely terrifying young woman."

The message is plain: stories are better when they end. Open-ended stories, stories that exist solely to heap battles upon a hero, only ever end in misery. I think if you look at, say, Spider-Man's history, really look at it, you'll wonder how one man can sustain so much pain and keep on living. The pat answer is "because he's a hero!" The real life answer is because... his story isn't allowed to end.

Moore and O'Neill stumble when they begin to critique modern culture. Late in 2009, Mina says, "I-it's not just the poverty. People were desperately poor in 1910, but at least they felt things had a purpose. How did culture fall apart in barely a hundred years?" Orlando responds, "By becoming irrelevant, same as always."

This is essentially the high concept for 2009 and I don't buy it. Past critiques in the series tackled everything from sexual mores to appropriate violence and did the job well. But the more modern critiques in 2009 feel half-baked or worse. The integration and critique of JK Rowling's Harry Potter novels feel snide. Andrew Norton, the Prisoner of London, refers to the magic of Rowling's novels as "sloppily-defined magical principles." A train is referred to as "a child's idea of how a train ought to work" and the general Potter feel as being "constructed out of reassuring imagery from the 1940s."

The Harry Potter critique feels lazy in light of the deft work Moore & O'Neill accomplished elsewhere. James Bond as a raping, worthless thug is both true to the character's earliest form and a valid critique of a long line of sexy cold war spies. Casting Dame Judi Dench's M as having been Emma Peel earlier in her career is one of those ideas that's simultaneous stunning and obvious. It's elegant, actually, the sort of idea that extends the life and mystery of two otherwise unrelated series.

But the most the Harry Potter novels get is "Oh, it's poorly written and the magic sucks." I don't see any of the imagination and craft that makes the LoEG series so interesting in these ideas. It feels like a jab, and worse than that, a mis-aimed one. Moore and O'Neill have the writing and drawing chops to skewer anything, but they miss the mark here.

But that's a smaller problem. The biggest problem is that I just don't buy the premise that modern culture is fallen and awful, especially compared to the culture of the past. I find the idea odious, actually. LoEG, as a series, is littered with offensive stereotypes, from Fu Manchu to a sex-focused golliwog. These ideas are from our past, and they are terrible. They're used to prop up white supremacy, and Moore and O'Neill do very little, if anything, to defuse or examine that history. They simply take the characters as they were used in the past and extrapolate their further usage from there.

To prop up stories from that period of time, stories that were rife with flagrantly racist stereotypes and ideas as just a matter of course, as being better than ours is... wrongheaded. It rejects one hundred years of progress, of burgeoning equality and increasing acceptance, in favor of "Stories had a purpose back then." It's a variant of the "Things were better in my day" argument, and it feels like a joke. It's so thin as to be unbelievable, and that feeling doubled when I saw the deus ex machina at the end of the book. The ultimate modern magical hero is defeated by... a magical hero from 1934? There's a subtext there that I don't like at all.

That hamstrings the rest of the book. If I can't buy the idea that modern culture is fallen, then the utter misery that infests the rest of the book is harder to believe in. Mina was institutionalized for forty years, never aging a day in the process, and the hospital's administration only had the barest idea of something fishy going on. Orlando was in the military, or perhaps a series of armies, for almost forty years, too. Quatermain was addicted and homeless for much of that time. Prospero, the League's benefactor, never checked in because...? Quatermain never tired of living in a gutter for decades because...? No one at the hospital launched a genuine investigation into Mina's past and predicament because...?

In other words, it feels like Moore & O'Neill wanted to show us that the world was a fallen, awful place, and instead of arriving there organically, they just moved their pieces into position. The status quo isn't unbelievable, but it does sorely test my suspension of disbelief that things had been miserable for so long, that they got to this point in the first place. I don't believe that today is all sunshine and vita-rays, but I don't believe in the despair Moore & O'Neill depict, either.

The rub, though, is that Moore & O'Neill are fantastic at the human side of things. Despite their unlikely situations, I believe in Mina, Orlando, Allan, Emma, and the rest. Harry Potter's frantic and obsessive attempts to avoid his destiny ring true, as do Quatermain's rejection of heroism. 2009, like the rest of Century in fact, is positively teeming with these little human moments that make all the difference. Orlando buying a rose for Mina. Mina pulling on her scarf as she comes back to herself after 40 years alone. Emma Peel reminiscing over a lost love. Quatermain convincing himself to do the right thing. Orlando having trouble unwrapping Excalibur during the big fight. Desperate sex before the end of the world. The terror of immortality.

Orlando's trip to the store and her apartment is as human as anything I've ever read, something that grounds the character for us, so that when she does extraordinary things later, we believe it.

What kept me going through 2009 despite the lackluster cultural critique, was the human element. It's resonant and familiar and comfortable and warm and wonderful. Moore & O'Neill clearly, clearly know exactly what they are doing, and it shows in how honestly and heartfelt the characters and their actions come across. I don't believe in the world, but I do believe in the characters, and I think that counts for a lot.

I have mixed feelings on the plot, but I greatly enjoy the fact that I can have those feelings and still feel like League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century was time well spent. Things don't always work out that way, but Moore and O'Neill are so talented that the good bits of 2009 far outweigh the bad ones.

Further reading:

-Jess Nevin's fantastic annotations for The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Century: 2009.

-The Mindless Ones sprawling and enlightening annocommentations for the same.

More From ComicsAlliance