How Deadpool Became the Most Exposed Character in Comics, and Why We’re Totally Fine With It

It's hard to remember that there was a time when even Wolverine was nothing more than just another inscrutable loose cannon known for killing, but that's exactly what he was before he gained his notoriety. As the character was handled by more and more able creators, he evolved into something more specifically defined, but those were the characteristics that first made Logan the most interesting cat in the Marvel U. Lo and behold, those same tactics worked to give Deadpool his primary foundation until he developed into the Merc with a Mouth we know and love.

It's hard to remember that there was a time when even Wolverine was nothing more than just another inscrutable loose cannon known for killing, but that's exactly what he was before he gained his notoriety. As the character was handled by more and more able creators, he evolved into something more specifically defined, but those were the characteristics that first made Logan the most interesting cat in the Marvel U. Lo and behold, those same tactics worked to give Deadpool his primary foundation until he developed into the Merc with a Mouth we know and love.

With those two icons serving as loose pater-familia, Deadpool has ended up here; as the star of a trio of ongoing series and a slew of one-shots and minis. He's got a Hollywood `It' actor signed on to play his psychotic role in a solo feature. It's good to be Wade. And it all began with an innocuous debut in "New Mutants #98" nigh twenty years ago. These many years later, the most memorable non-mutant character to emerge from the X-book is still tearing up the Marvel Universe like a blade-wielding hyena on Ritalin.

It's been a long road for the guy who goes by the name of Wade Wilson, (though that might not be his real name, on account of T-Ray is a dick).

No Marvel creation has resonated better since the debut of The Punisher. Deadpool has endured a debut in a notoriously underwhelming creative era, shamelessly derivative, convoluted X-roots, and even one of the worst Hollywood chop-jobs in comicbook history, (really!? You're going to sew shut the mouth of the character defined by his verbosity? Fail guys, fail). Just how far has Deadpool come? Consider that on the first page of the character's existence, he correctly uses the word "fastidious."

Comic book readers are known to be fickle, and slow to warm to new costumed characters, but Deadpool's stock has risen steadily since his unveiling. Now the Merc with the Mouth stands on the threshold to go from cult favorite to household name.TAD-POOL

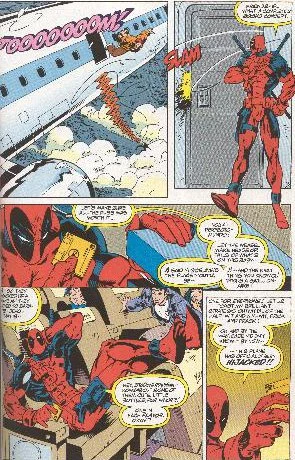

Render-man Rob Liefeld was the pouch-loving force driving the New Mutants bus, but judging from the early follow-up series and the characteristics that have withstood the test of time, it was writer Fabian Nicieza that instilled the persona and laid the groundwork that saved the crimson and black hitman from the obscurity that swallowed up so many of his contemporaries. Deadpool was the deranged cousin of Spider-Man, sharing both a body-sock costume and an unwillingness to ever shut up. He wasn't quite an anti-hero, he was more of an anti-villain; less defined by his altruism than by the worse evils he was pitted against. Oh, and he combined swords and guns in a way that none of us had yet dared to dream.

It didn't take much for a character to get his own miniseries in the early 90's, when new comics and embossed covers flooded the market like stink fills a subway, so it didn't take long for Wade to get a title all to himself. The first two such minis, "The Circle Chase," and "Sins of the Past," bore out to be artistic proving grounds for future superstars, showcasing the early work of both Joe Madureira and Ian Churchill. Joe Mad laid pen to 'Pool first, and his interpretation offered a stark contrast to the earlier Liefeld depiction. Where Liefeld's 'Pool, inconsistent though it could be, was relatively spindly and jagged-edged, Madureira channeled his energy into a more bulbous and broad figure, creating a visual distinction between he and his Web-Head brethren.

Co-creator Nicieza wrote the first mini, "Circle Chase," and laid the foundation for a character that had emerged from the familiar Weapon X program. The most famous Weapon X-alum (think 'Snikt,') had coped with the invasive tragedy of the inhumane program with berserk savagery, but Wade Wilson's wiring was such that abject lunacy was his only antidote to the place that made artillery out of men. As he was created, Deadpool was a straight villain. He was a mercenary, a for-hire killer, but there was already something about him that readers responded to. He was a jokester, and no matter how malevolent comedians might be, people are often drawn to their charisma. The same trigger that makes gallows humor acceptable makes compelling the comic about the guy sending some forgettable hero to the gallows.

Deadpool was slicing, dicing, and side-splitting. "The Circle Chase," was a story of old blood debts left unpaid, and it operated in that obscure, self-referential corner of the universe where only X-Men fear not to tread. It succeeded in making Deadpool into more than a run-of-the-mill X-villain, but it didn't leave him fully prepared to be ingrained in the Marvel Universe at large.

Deadpool was slicing, dicing, and side-splitting. "The Circle Chase," was a story of old blood debts left unpaid, and it operated in that obscure, self-referential corner of the universe where only X-Men fear not to tread. It succeeded in making Deadpool into more than a run-of-the-mill X-villain, but it didn't leave him fully prepared to be ingrained in the Marvel Universe at large.

Mark Waid and Ian Churchill's "Deadpool," miniseries, later retitled "Sins of the Past," took the groundwork of the previous mini and polished it. It was Waid's work that made the character's first dent in shattering the 4th wall between he and the reader, and it was Waid who definitively entrenched Deadpool as the erratic Bugs Bunny figure that has made him the unique patch of the Marvel quilt that he is. Churchill's pencils were crisp and strong, enough to hold up against the slick art of the time, but there was little new about the visuals, and it shared the overwrought features of its era. What "Sins of the Past," did best was to bring a level of subtlety to the characteristic blueprint Nicezia had already laid out; including 'Pool's underlying fragility. A budding but hopeless romance with the mutant hero Siryn exposed Wade's vulnerability. There's nothing like a little puppy-love to distract an audience from the unseemliness of rooting for a career murder. Additionally, Waid made a point to diminish Deadpool's unlimited healing powers, a move that played up the more literal vulnerability of the character- a savvy move, as audiences expect more uphill struggle out of a protagonist than for an antagonist.

MERC WITH A MONTHLY

With a few successful limited engagements under his belt, Deadpool was finally ready for prime time. Deadpool's next titular venture was a breakout ongoing series by Joe Kelly and Ed McGuinness. The collaboration by the pair has long been considered a creative high point for the title, and, to some, even a high water mark for Marvel comics of the 1990's. The book took cues from each previous incarnation, lovingly perfecting the antisocial antihero. The jokes clicked and the visuals sang. Deadpool's humor had always been pop-culture heavy, but Kelly brought an ephemeral triviality that succeeded, not in trying to be funny, but in being funny. McGuinness took the Manga-influenced, rounded edge approach that had made Maduriera's rendition memorable, and pared it down to its streamlined core. His minimal line gave a cartoonishness to the book that suited its tone perfectly. The world looked about as serious as Wade took it, without sacrificing a bit of the kinetic action.

With a few successful limited engagements under his belt, Deadpool was finally ready for prime time. Deadpool's next titular venture was a breakout ongoing series by Joe Kelly and Ed McGuinness. The collaboration by the pair has long been considered a creative high point for the title, and, to some, even a high water mark for Marvel comics of the 1990's. The book took cues from each previous incarnation, lovingly perfecting the antisocial antihero. The jokes clicked and the visuals sang. Deadpool's humor had always been pop-culture heavy, but Kelly brought an ephemeral triviality that succeeded, not in trying to be funny, but in being funny. McGuinness took the Manga-influenced, rounded edge approach that had made Maduriera's rendition memorable, and pared it down to its streamlined core. His minimal line gave a cartoonishness to the book that suited its tone perfectly. The world looked about as serious as Wade took it, without sacrificing a bit of the kinetic action.

Writer Joe Kelly outlasted McGuinness on the project, constructing an overarching storyline that directly addressed Deadpool's conflicted nature. From the book's inception, it had explored the struggle between the inner goodness of a man who's life was defined by brutality, and his innate desire to overcome those violent circumstances without knowing how. The major through-line to the series was Wade being slowly convinced that he had a heroic destiny, only to realize that his fate as a hero was no less unsavory than it had been as a villain, even as a reluctant one. This solidified Deadpool's standing as one who existed in the gray middle- neither good nor bad, simply a wild card waiting to be played in either direction.

The series was also successful in removing Deadpool from his X-trappings, and giving him a community all of his own. He was given his own arch-nemesis, T-Ray, who's origins were a dark echo of Wade's own. He had a supporting cast, a mission, and a spitload of irreverent jokes. Kelly kicked the character's penchant for internal monologue up to 11. A stream-of-conscious style narrative finally burst through that mystical fourth wall, acknowledging that somehow, due to Deadpool's mental imbalance, he knew he was a star of a comicbook, and that he was that much more eager to entertain. The humor of the book served to bring a lighthearted flavor that could offset the serious issues of derangement it would often explore.

The series sustained past its shelf life, and eventually devolved, the way only a comicbook can, into a book about itself. Deadpool's mysterious origins were unveiled, first reinforcing that he was once a man named Wade Wilson, then that he wasn't, then becoming a book about Deadpool as an amnesiatic Agent X, who wasn't Deadpool, until the title became just as Byzantine as the X-Men books it had once escaped. It was unceremoniously canceled, and Deadpool was once again relegated to the sidelines, awaiting his next shot.

POOLING TOGETHER

It was co-creator Fabian Niceiza who finally got Deadpool off the bench, casting him in the buddy role alongside his first adversary in the "Cable & Deadpool," series. Over a decade after their first meeting, the two Rob Liefeld creations still had enough cache to justify a series of their own, even if they had to share it. The characters seemed to have common issues- they were recognizable, but both seemed to be defined by the broader context of their worlds, not able to stand up on their own. Cable was the time-traveling son of Cyclops and a clone of Jean Grey infected with a techno-immune disease by the X-Men's most confusing adversary. Deadpool was the product of the same program that had made Wolverine, without ever having shared a meaningful appearance with Wolverine. They were fundamentally derivative. Teaming them up was a solution that didn't really solve the problem, it didn't raise the ceiling for the characters, but it served to cater to the same audiences that was already able to identify them both.

It was co-creator Fabian Niceiza who finally got Deadpool off the bench, casting him in the buddy role alongside his first adversary in the "Cable & Deadpool," series. Over a decade after their first meeting, the two Rob Liefeld creations still had enough cache to justify a series of their own, even if they had to share it. The characters seemed to have common issues- they were recognizable, but both seemed to be defined by the broader context of their worlds, not able to stand up on their own. Cable was the time-traveling son of Cyclops and a clone of Jean Grey infected with a techno-immune disease by the X-Men's most confusing adversary. Deadpool was the product of the same program that had made Wolverine, without ever having shared a meaningful appearance with Wolverine. They were fundamentally derivative. Teaming them up was a solution that didn't really solve the problem, it didn't raise the ceiling for the characters, but it served to cater to the same audiences that was already able to identify them both.

The book was basically about Cable's endeavors in trying to save the world and blah-blah-blah. He'd have a plan, then Deadpool would screw it up. Lather, rinse, repeat. It wasn't until Cable was taken off the board that Deadpool's trademark brand of fun began to fully permeate the title. It became a romp through the obscure corners of the Marvel Universe, pitting Deadpool against the likes of Ka-Zar and Brother Voodoo. If this venture was meant to save the title, it was a doomed one, because one can't increase the popularity of a character beyond its already existing fanbase by the inclusion of even lesser known characters. But it did succeed in recapturing a bit of the high points of Deadpool's previous iterations, and bringing his potential back to the forefront. It also gave us one of the great "We're already canceled but screw-it, we're going out with a bang," stories in "Cable & Deadpool # 50," which included the most insane opponents in Deadpool's, and lo, Marvel's, history- Venom symbiote dinosaurs. It just doesn't get better than that.

FINDING HIS WAY

Deadpool next showed his scarred mug in the pages of Daniel Way's "Wolverine: Origins," series, sporting some brand new narrative gimmicks. Pool-o-vision is a pretty simple trick; every once in a while, when Wade Wilson's schizophrenia reaches a fever pitch, he has a non sequitur vision of his somewhat fractured take on reality. It's a sight gag perfectly tailored to a sight medium, and hey, there's always a good reason for an artist to draw a panel of something happily irreverant. Pool-o-vision is a bit reminiscent of the comical cutaways of the old Looney Tunes cartoons, which is perfect considering the way Deadpool acts as the Bugs Bunny wild-agent of the Marvel Universe.

Deadpool next showed his scarred mug in the pages of Daniel Way's "Wolverine: Origins," series, sporting some brand new narrative gimmicks. Pool-o-vision is a pretty simple trick; every once in a while, when Wade Wilson's schizophrenia reaches a fever pitch, he has a non sequitur vision of his somewhat fractured take on reality. It's a sight gag perfectly tailored to a sight medium, and hey, there's always a good reason for an artist to draw a panel of something happily irreverant. Pool-o-vision is a bit reminiscent of the comical cutaways of the old Looney Tunes cartoons, which is perfect considering the way Deadpool acts as the Bugs Bunny wild-agent of the Marvel Universe.

The other tool Way introduced in his "Wolverine: Origins," tale was the competing inner-monologue captions bickering about Deadpool's head. The voices in Wade's head act as a Greek Chorus for his mercenary escapades, only they offer more hostility and sarcasm. Every new solo adventure comes fully equipped with a supporting cast, albeit a discorporate one. The captions will argue, with each other or with Deadpool's external dialogue, and generally incite hilarity. They also serve a greater purpose. The cacophonous captions also provide an amount of rationalization to Deadpool's penchant for breaking the fourth wall. The audience is privy to a conversation that none of the comicbook's cast save the star can hear, so that compromised "wall" is more of a partition than a load-bearing one. It is a subtle justification, but a significant one as it serves to maintain the narrative integrity, even in a whacked-out way.

Way took his new 'Poolbox and used it to launch an all-new, high visibility ongoing Deadpool series. Artist Paco Medina was brought on board, continuing the cartoonish and curvy style laid out by both Maduriera and McGuinness before him. The book tied in with the heavily marketed "Secret Invasion," event, depositing Deadpool right in the heart of the broader ongoing Marvel narrative. The decision was likely equal parts editorial and commercial. If the intention was to popularize what had been a marginal character, what better exposure is there than to have him at the crux of the most important story of the day? It's a matter of visibility. It also made sense commercially, as it is easier to dovetail into an already existing marketing campaign than launching a new one.

So Deadpool killed some Skrulls, and inadvertently helped Norman Osborn become king of the world. It would have made perfect sense to close out that initial story arc, and then push Wade on to his own adventures. But that wasn't what happened. Not exactly, anyway.

Instead, Wade was kept at or around the heartbeat of the Marvel U. The "Secret Invasion," arc was followed by a "Dark Reign," one, exploring Deadpool's place in the Marvel world' new status quo. He squared off against Norman's squad of goons, the Thunderbolts. He fought, he won, he felt ambivalent about it, and he went on a cruise. Then, when he returned home in issue 15, he tried to join the X-Men, and live in their "Utopoia." Even his most recent team-up with Spider-Man seems to be more of a vehicle for the new Hit-Monkey character than a straight story.

What's interesting about this series of events is not the events themselves (I mean, they are, but not in a 25 word summary...); what's interesting is that Marvel editorial decided that the most prudent thing to do with Deadpool's signature ongoing series was to make it a satellite book for the broader goings-on of the greater Marvel story. From the wide angle, it seems as though it's the outside "events," that are setting the pace of the plot, not the main character himself. Again, as with the launch, this might be as prudent a decision in terms of marketing as it is to editorial, but it is noticeable nonetheless. The stories don't feel forced; there is sound justification for each and every developing tie-in, but it still creates a vague sensation that Deadpool isn't driving his own bus. Maybe it's one of his voices.

DIVERSITY OF DEADHEADS

For a character to have one ongoing series puts him in rarefied air in the comics' community, but multiple ongoings are usually saved the premiere Batman/ Superman/ Spider-Man/ Wolverine class. Deadpool joined that heady company with "Deadpool: Merc with a Mouth," a book with about as gimmicky a gimmick as one can get. It stars Deadpool, much like one would expect, but with the costar of Deadpool's alternate reality, zombie disembodied head. It's the Merc... and the Mouth. Yeah. Writer Victor Gischler and artist Bong Dazo did an admirable job making ridiculous out of the... ridiculous, but there seemed to be little justification for this series beyond the crass gouging of a loyal following. It didn't exactly offer tremendous new perspective on the character, instead sort of bouncing around alternate universes. The clever hook has been adequately executed, but without a clear mission statement or function, this long seemed to be a miniseries posing as an ongoing.

For my money, the most inspired Deadpool story to grace the shelves of late was the work of Mike Benson, Adam Glass, and Carlo Barberi on the "Deadpool: Suicide Kings," miniseries. This mini set 'Pool against the likes of the Punisher, Daredevil, and Spider-Man. In pitting Wilson against Marvel's `street level' characters, Deadpool was defined in contrast to those better- known commodities. Even when working together with those characters in an collaborative, but adversarial manner, it distilled the functionality of Deadpool in that shared universe. In some ways, it was a graduation for the character, because it showed he was as soundly trenchant and fully realized as three Marvel Studios franchises, not as a qualitative judgment on heroism, but rather on the effectiveness of servicing a narrative.

For my money, the most inspired Deadpool story to grace the shelves of late was the work of Mike Benson, Adam Glass, and Carlo Barberi on the "Deadpool: Suicide Kings," miniseries. This mini set 'Pool against the likes of the Punisher, Daredevil, and Spider-Man. In pitting Wilson against Marvel's `street level' characters, Deadpool was defined in contrast to those better- known commodities. Even when working together with those characters in an collaborative, but adversarial manner, it distilled the functionality of Deadpool in that shared universe. In some ways, it was a graduation for the character, because it showed he was as soundly trenchant and fully realized as three Marvel Studios franchises, not as a qualitative judgment on heroism, but rather on the effectiveness of servicing a narrative.

The character had finally superseded its derivative roots, and now, it seemed, everybody wanted a dip in the 'Pool. In keeping with the general absurdity of Deadpool, a celebratory and numerically unfounded anniversary issue was released; "Deadpool #900." No, there had not been anywhere near that number of Deadpool comics published, but the oversized issue offered a unique opportunity for creators past and present to tell Deadpool-inspired vignettes. Most noteworthy of all was a collaboration between original artist Rob Liefeld and ongoing series architect Joe Kelly, whose tale hearkened to Deadpool's mysterious backstory.

Perhaps taking a note from the successes of "Suicide Kings," "Deadpool #900," was followed by the equally unlikely "Deadpool Team-Up #899." "Team-Up," took the clear role of showcase book, once again leading Deadpool to some of the more obscure corners of the Marvel narrative. Forgoing a regular monthly creative team for a rotating crew of writers and artists, the diversity of "Team-Up," makes it a regularly satisfying read. Each reverse-numbered issue (#899 was followed by #898, and so on) exposes Deadpool to some new element throughout Marvel's publishing line, allowing for appropriately whimsical adventures.

In many ways, "Deadpool Team-Up," is the product of nearly two decades' worth of ground laying. It celebrates the character as a steady mainstay of a title where creators import other, lesser refined guest stars to try and share Deadpool's bright spotlight. By carrying his own "Team-Up," book, with a parade of B and C-listers, Deadpool is unequivocally defined as an A-lister in contrast.

CORPS PRIDE

Where "Deadpool Team-Up," defines Wade Wilson in contrast to his Marvel peers, "Prelude" and the subsequent "Deadpool Corps," seem likely to define him in contrast to himself, or rather, himselves. "Merc with a Mouth," writer Victor Gischler has assembled an array of alternate Dead-pool-gangers, including the aforementioned Headpool, Lady Deadpool, Kidpool (once known as Kid- Deadpool), and Dogpool in the interest of... well, I suppose we'll see, (maybe saving the universe?). Personally, when I hear "Dogpool" I fully expect a savage, growling bout to the death with Dilbert's Dogbert, but in all likelihood that's not in the cards.

If this new ensemble series keeps in the tradition of 4th-wall destruction, "Deadpool Corps," should be a satirical commentary on heavily marketed "event" comics as well as a send-up of Deadpool's own overexposure. This seems to be the case in the early going, as the first issue was rife with references, from The Beyonder from "The Secret War," to a Lobo-riff character. "Prelude," showcased a diverse array of artists, getting contributions from Rob Liefeld, Whilce Portacio, Philip Bond, Paco Medina and Kyle Baker, all of whom were able to show the expansive range of the character and his offspring. "Deadpool Corps," is as silly as any Deadpool story told. If the sheer volume of Deadpool books currently being sold is a testament to Deadpool's realization as a heavy hitter among comics' characters, "Deadpool Corps" is a testament to the consequences of such mass popularity.

WADING THROUGH THE POOL

With Deadpool's exposure level where it is, it's shocking that he hasn't been arrested for indecency. But the character, through the hard work of a multitude of talented creators, has earned his spot at the peak. Charting the trajectory of a commercially owned character in advance is an impossible task, because no one hand can guide it forever. This means that while the originators can claim a modicum of ownership for long-term successes, a once in a generation rise to prominence like Deadpool's is ultimately a success of the collective. Even fans, who exercise their opinions via pure purchasing power, share in the achievement. It takes a great deal to graduate from simply being derivative of Spider-Man and Wolverine to being a near equal peer to those titans, but that is exactly what happened.

Now, when it comes to visibility, he's the Merc with the Most. And he has a posse.

More From ComicsAlliance