The 5 Worst Comics of 2010: #1 — Superman: Grounded

Initially intended to be a twelve-issue story following Superman as he walked (adamantly not flying) across America and reconnected with the country and its people, "Grounded" became more a publishing irregularity than anything. It's the Superman story that J. Michael Straczynski abandoned to write a different Superman story, one that's more lucrative and targeted to a wider audience. Straczynski ended up managing four – #701, #702, #703, and #705 – and then called it a day.

I have no idea what Straczynski ultimately intended to say with "Grounded," and since he isn't finishing the story, I'll never know. But Superman #701 reads like a mini-thesis of its own, and it has a very clear message: Anyone who criticizes this comic is stupid and shallow and should shut the hell up.

The comic is crazy defensive from the get-go, obsessed with boxing out its inevitable critics by devoting four full pages and parts of three others to condescending to belittling or humiliating reader stand-ins who dare to question the wisdom of the story Straczynski has chosen to write. Reporters ask Superman questions and get disdainful, witheringly minimal non-answers in return. One reporter gets aggressive with his questioning, and so Superman physically humiliates him.

Lois Lane makes an appearance to ask some of the same questions the reporters ask, but since she has sex with Superman he dismisses her with a slightly warmer flavor of condescension. She's the good fan, the one willing to trust in Straczynski/Superman that this whole walk-across-America really is a good idea, and not just an empty high-concept pitch line. The rest of the reporters are the bad fans, the small-minded ones who wander away a few pages later, complaining that "You can't make a story about a guy walking down a street."

At the end of Superman #701, a random man-on-the-street asks the perfectly reasonable question of why a hero like Superman is wasting time on a preposterously long walk, time that could be spent on any number of other things. I'm reprinting Superman's reply in full, below, because a summary or quote just won't do. This is the penultimate page of the comic, leading into the final splash. The construction of the comic therefore makes this THE point of the story. Here it is:

To be clear: Henry Thoreau spent one night in jail for not paying his taxes. His aunt paid his bill the next morning, and he was released. The friend that visited him was Ralph Waldo Emerson, who presumably did pay his taxes, and Thoreau's bars of principles extended to accepting a place to live on Emerson's land near Walden Pond, and then in the Emerson family house, where he ate Emerson's mother's food while he wrote Walden, a book about his self-sufficient simple life in the woods on Emerson's land near Walden Pond. Thoreau would also dine out on his night in jail for years to come, writing Civil Disobedience, which is a book with a lot of good ideas in it, but the writing of which doesn't mean that Thoreau actually ever sacrificed much at all for what he believed in. All of which is fine -- my point is not to attack Thoreau, but to attack the idiocy of using him as a simplistic bludgeon against people to whom you wish to feel superior.

What Straczynski wants is for Thoreau to function as an easy metaphor for the misunderstood hero, the guy who does something crazy out of principle and gets ragged on by the scared drones around him who see anything that shakes up the status quo as a threat. I understand why Straczynski wants that -- it's an appealing, flattering metaphor to apply to your main character, particularly when that main character is clearly acting as a channel for your own posturing.

What Straczynski wants is for Thoreau to function as an easy metaphor for the misunderstood hero, the guy who does something crazy out of principle and gets ragged on by the scared drones around him who see anything that shakes up the status quo as a threat. I understand why Straczynski wants that -- it's an appealing, flattering metaphor to apply to your main character, particularly when that main character is clearly acting as a channel for your own posturing.

The problem with making Thoreau a generic patron of holier-than-thouness, though, is that it ignores that his principles weren't generic. He wasn't against abstract "injustice." He had very specific political reasons -- opposition to slavery and to the Mexican-American War -- for not paying his taxes, and his actions and public statements were stridently against the prevailing attitudes of the general populace. He spoke out in defense of John Brown, for crying out loud, a man who encouraged armed insurrection against the U.S., who killed slave-owners in American territories, and who most of America considered a terrorist and a murderer. Thoreau may have only spent one night in jail, but it was the result of some pretty heavy, risky opinions.

What are Superman's great controversial moral stands in Straczynski's run? Well, he's not fond of drug dealers, he's against illegal immigration unless America gets something out of it, he's for sweetheart government deals for corporations to jumpstart the economy, and he thinks child abuse is just awfully tacky. WAY TO GO OUT ON A LIMB, BIG GUY. You're such a maverick. Superman isn't the principled outsider in these comics. He's the roving monitor of the status quo.

In Superman #701, our hero runs some black drug dealers out of a foreclosed neighborhood in which they've set up shop. (These are, it should be mentioned, the first and nearly only black people he meets while walking through Philadelphia, a city with a higher proportion of African-Americans than New York City.) Superman's brilliant strategy for getting rid of the drug dealers is to set fire to the drug stashes in each of their houses with his heat vision, and then... leave. Now, I guess you can read the comic and assume that he has the whole thing under control because, you know, he's Superman. But setting a half-dozen large fires throughout a neighborhood and then just walking away seems stupid.

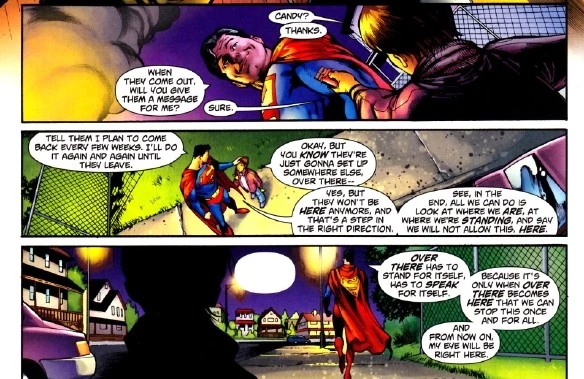

As he leaves, Superman comes across a magical white child who appears and offers him candy. Superman smiles, asks this random little kid to deliver a message to the drug dealers for him (?!?), and then gives a total nonsense speech. I have to show you this one in its entirety, too:

WHAT IS THAT LUNATIC TALKING ABOUT? He's arbitrarily chosen this neighborhood to keep an eye on, but the next neighborhood, well, it's just up a creek. That neighborhood has to "stand for itself." What? How hard would it really be for Superman to, say, keep an eye on both neighborhoods? My guess, since he's going to be checking in on this one only every few weeks, presumably by flying in from Metropolis for about 30 seconds: not that hard.

This is the problem with trying to tackle "real world" problems in a "serious" way with a character like Superman. He's basically God. He can walk into a neighborhood full of drug dealers and just magically destroy all their drugs and drive them off. In order to explain why he doesn't just do this all the time, or any number of other things that he could do with minimal effort that would drastically change the lives of every single person in the country, if not the world, writers like Straczynski resort to utter inanity. "Over there has to stand for itself, has to speak for itself, because it's only when over there becomes here that we can stop this once and for all." Read that sentence again. It means nothing.

"Grounded" is full of this kind of ponderous, pretentious gobbledygook, meant to show the reader how important and thoughtful it all is. Over and over, Straczynski inserts shrill arguments for how seriously the reader should take this pointless exercise in Superman solving "real" problems through glib assertions of nonsense axioms and generous application of brute force and intimidation. It's made all the more ludicrous, then, by Straczynski leaving mid-thought, before delivering any of the intellectual meat promised by the self-important build-up.

Instead of being some grand statement on heroism and America, "Grounded" is just one introductory issue bloated with preposterous ego, two mediocre and forgettable Superman stories in #702 and #703, and then #705, a rushed piece of mechanical hackwork featuring a child abuse story made up of half-remembered garbage cliches from network television specials 20 years ago.

Aaaaaand scene. Exit Straczynski, stage left, to the sound of 1,000 flatulent windbags vigorously deflating.

-Jason Michelitch

More From ComicsAlliance

![Dynamite Announces ‘Twilight Zone,’ ‘Bob’s Burgers,’ ‘Heroes,’ ‘Voltron/Robotech’ And Alice Cooper Series [SDCC 2013]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2013/07/dynamitesdccbobsburgersvoltronrobotech.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![War Rocket Ajax #118: The Crew Breaks Down Dan DiDio’s Favorites, Part Two [Podcast]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2012/06/ajax118.jpg?w=980&q=75)