![Congressman John Lewis And Andrew Aydin Talk Inspiring The ‘Children Of The Movement’ With ‘March’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2013/09/Lewis-hed1.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Congressman John Lewis And Andrew Aydin Talk Inspiring The ‘Children Of The Movement’ With ‘March’ [Interview]

My parents were born, poor and black, in the south in 1943. My father was two years younger than Emmet Till, and my mother was living in Alabama when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus. When I was a kid, my father would tell me about the Civil Rights movement, and the people who helped shape it. He'd tell me stories about Martin Luther King Jr. and Roy Wilkins, about Rosa Parks and Claudette Colvin, about a bridge in Selma and a boycott in Montgomery. And he'd tell me stories about Congressman John Lewis.

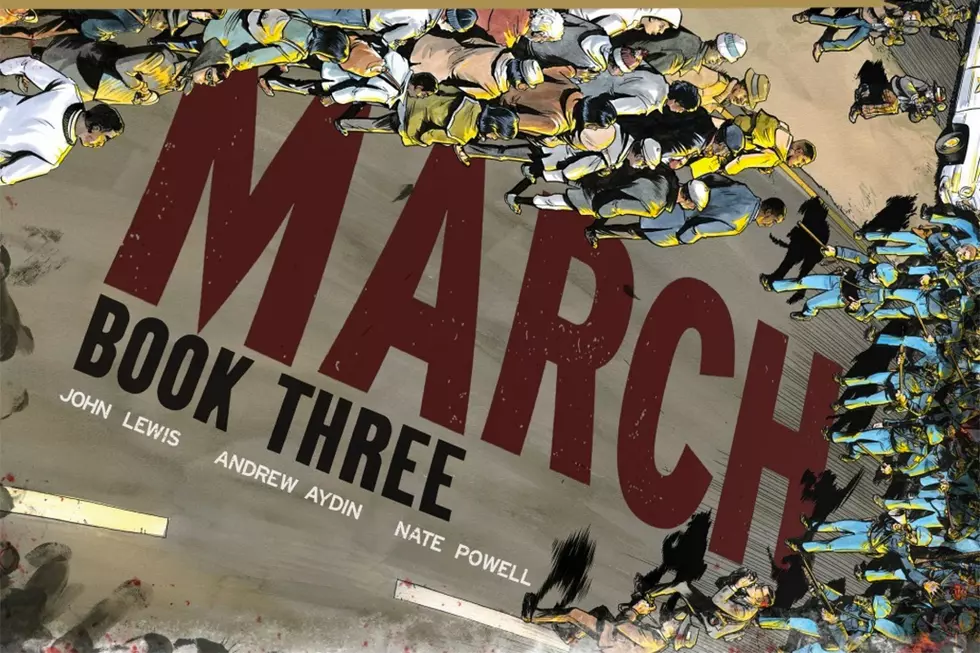

In stores now is March, the first installment of three autobiographical graphic novels written by Congressman Lewis -- a U.S. Representative from Georgia and a Civil Rights icon -- co-written by congressional staffer Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell. March tells the story of Congressman Lewis' life, from humble beginnings in Troy, Alabama during the Jim Crow era south, to being one of the 10 speakers at the March On Washington, to eventually being elected to the U.S. Congress. Congressman Lewis is one of the most significant figures in modern United States history. As such, his life story is significant, and he's decided to share it with the "children of the movement" with his new comic, published by Top Shelf.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Congressman Lewis and Aydin, to discuss the decision to tell this story through a comic, the choices the congressman has made in his life, and how they both hope this book inspires the next generation to do more.

ComicsAlliance: I’d like to start off by talking about Martin Luther King Jr. And The Montgomery Story, the 1956 comic distributed throughout the south to teach the non-violence movement. The comic has made its way to several other spots in the world, from South Africa during the era of Apartheid to Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring. In March you talk about being introduced to it. What did you take from that experience that informed your decision to write your own comic more than 50 years later?

Congressman Lewis: Well, growing up in rural Alabama, 50 miles south of Montgomery, I’d heard of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and the bus boycott when I was 15 years old, in 1955. And I went away to school, to Nashville, and after being away in Nashville for about two and a half years, I came in contact with Jim Lawson. Lawson was working for the Fellowship Of Reconciliation, or the F.O.R. He was the one who introduced me to the comic. I read it, and I saw it as a piece of moving history at the time. It just made it very plain, it made it very clear, the power of the philosophy and the discipline of non-violence. And Jim Lawson became my teacher, my trainer. And every Tuesday night for that entire school year, a group of 20 or more school children from Fisk University, Tennessee State, Vanderbilt, and American Baptist College would meet, and we would study the way of peace, the way of love, the way of non-violence. And The Montgomery Story, this comic book that sold for 10 cents, became like our Bible. It was our guide. And I think it helped compliment what Jim Lawson was teaching. It made it simple, it made it plain and it made it very clear. What happened in Montgomery, for more than 380 days, that a people came together, with the purpose of ending segregation and racial discrimination on the bus system in Montgomery. They did it in a peaceful, orderly, non-violent way. There were people who bombed homes and churches, harassed people, but the participants didn’t engage in any acts of violence.

ComicsAlliance: Andrew, you were introduced to the comic by Congressman Lewis, and then you sought it out. First of all, how difficult was it to find a copy, and second of all, when you read it, was your immediate reaction “I have to convince the Congressman to write his own comic?”

Andrew Aydin: Well, when he first mentioned it to me, I went and read the section in his memoir Walking With The Wind, where he talks about how the Greensboro Four read it. And then I did what most of us would do: I Googled it. There were some digital versions of it, so you could get pieces of it and see it firsthand. It actually took me several years to track down an original copy, and like most things I found it on Ebay [laughs]. But once he told me about it, and I connected those dots that a comic book had a meaningful impact on the early days of the Civil Rights movement, and in particular on young people, it just seemed self-evident. If it had happened before, why couldn’t it happen again? I think part of that impulse was born out of a frustration with the way things are in our politics and our culture. The election of Barack Obama seemed like it was opening a huge door, and I think perhaps we put all of our dreams and aspirations on him, and failed to recognize that we too have to rise up, and we too have to make our voices heard. He’s one man and can’t do it alone, and we did not make Congress, we did not make our state legislators do what we needed them to do to make the society we all imagined in that campaign. And when I look back on it, the Civil Rights movement was so successful at using non-violence in so many different ways: Birmingham, Montgomery, Selma in particular, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington, all held different aspects, and when you look back at the comic book it was one tactic. It was the way they did it in Montgomery. But what if we took the broader story and showed all of the different tactics. Because what worked in Birmingham and what worked in Montgomery didn’t necessarily work in Albany, and there were different reasons. The Sheriffs started adapting. They were moving prisoners out of city jails and putting them in county jails, and things like that, so you couldn’t fill them up as fast. And we need to adapt. The tactics, the principles, they still work, but we need to adapt our use of them. And so showing how others had done that and how it had progressed seemed like such a natural way to sort of pursue those ends.

ComicsAlliance: Andrew talked about your memoir, and I wanted to bring that up because March isn’t the first time you’ve written about your experiences. Had you always planned on writing about your life again, in a comic or otherwise? And how was putting your story into a visual form different from that experience?

Congressman Lewis: Well, from time to time I had dreamed about maybe doing a book about my congressional career, telling all of the ins and outs. But I had not dreamed of doing a comic book until Andrew really just said it to me, and he didn’t give up [laughs]. So I’m glad that he didn’t give up and didn’t give in. It’s a lot of fun to get out and talk about this book, and to see the reaction of people, especially teachers, librarians and children. Because it’s dramatic. It’s alive, it’s movement, it’s action.

ComicsAlliance: You just mentioned how much fun it’s been to promote this book. Comics are obviously a new world for you, and now you’re going to Comic-Con and other places to promoteMarch. What’s that experience been like for you?

Congressman Lewis: To have a parent, a grandparent, a teacher, say “all of the children should be reading this book,” to have someone say “this book should be in every school and every library,” that is very meaningful. And I hope people will read it, not only here in America but around the world, and be inspired to act, be inspired to do something.

ComicsAlliance: Andrew, what’s it like for you bringing someone of Congressman Lewis’ stature into this world that you are so familiar with?

Andrew Aydin: Well I think there are two sets of emotions. One is absolute sheer terror, because he’s also my boss [laughs].

Congressman Lewis: Well, I’m not a boss in that sense of the word.

Andew Aydin: No, you’re right.

ComicsAlliance: Let’s go with “supervisor!”

Andrew Aydin: [Laughs] But that’s what’s so wonderful about it, you know? Okay, let’s put it in a different way. I didn’t want to let him down. I didn’t want to put him in a place that made him unhappy or uncomfortable, and no other member of Congress had ever attempted anything like this. So when you’re doing something like this for the first time, you just don’t know how it’s going to go. You have a hunch, you trust your feelings, you trust your instincts, but in the end, what’s going to happen has yet to be written. So going to Comic-Con, and doing some of these events, they were a question mark. So for the reaction to have been so strong, and be so overwhelmingly personal and positive, it’s been something so special. It’s been unique. It’s something I’ll remember my whole life, and I know it’s something I’ll be telling my kids. There’s no way to describe it accurately because I don’t have anyone to talk to who’s been through this. And when you think about other members of Congress maybe doing this, and we’ve had people who have asked, whether they’re members of Congress or other people just wanting to tell their story, I don’t think anybody will ever be able to do this this way, because I don’t think anyone else has a story that should be told like John Lewis’ story. So I’m just glad I got to be here for this, I’m glad to be a part of it, and I’m glad that John Lewis had the faith in me to let me do this.

ComicsAlliance: It’s funny, because as you said, you really are the first. Obviously there dozens of autobiographical comics out there, so to be the first Congressman to do this, in a sense you’re trailblazing again, which seems appropriate: It’s another part of your story. Is that something you considered at all?

Congressman Lewis: Well no, not really. I think my whole life has been one of sort of daring, and sort of sailing against the wind instead of just going with the wind. You have to go with your gut sometimes, and how you feel. And with the encouragement of Andrew, over five years, I went with my feeling and my gut. And I think the spirit – you can call it what you want to, but I call it the spirit of history – is sort of guiding us on this journey. And I think the best is yet to come.

ComicsAlliance: There are so many moments in the book that stand out to me, and I’d like to talk about a few of them. The first is when you meet Jim Lawson, and you’re introduced to the F.O.R., The Montgomery Story comic, and the non-violence movement. You talk in the book about immediately going to some of your friends and saying “You have to come to this workshop with me.” And the part of the book that grabs me the most is when you discuss you and your colleagues sitting together and, in preparation for dealing with what you’ll have to in using the non-violence movement, you practice mistreating each other, taking each other’s dignity away. It’s a really powerful scene, and I think many of the people reading this will be introduced to that aspect of history for the first time. Looking at it now, do you feel that’s the kind of scene that has more of an emotional impact for a reader when actually seen visually?

Congressman Lewis: Well, it’s the way it happened, and you had to make it real, make it plain. It’s tough, when you go through role playing of social drama, and pretend that you’re going to pull someone off the lunch counter, spit on them, blow smoke in their face, pour hot water or hot chocolate or coffee on them, or just harass them and call them all types of names. These are your friends, your classmates, your schoolmates. It’s tough, but that’s the role you played and it’s sort of dehumanizing. But to do this to someone who may have been your roommate, and sometimes using the N-word to make the point, and to have someone like a Nate Powell, to come and make that as real and as simple as possible; it is much stronger and much better than just simple words.

Andrew Aydin: That was one of the scenes we went back and really talked through, because you want to show that not just as an example of what did happen, but as an example of what you should do to prepare yourself for what could happen.

ComicsAlliance: I want to get back to Nate Powell and his impact on the book, but there’s another moment I’d really like to discuss. About halfway through the book you have this kind of revelation where you think “I’m not doing enough.” You’ve talked about wanting to reach and inspire youth with this book. Is that a specific moment you hope resonates and motivates younger readers to do more?

Congressman Lewis: It’s my hope that, somehow or someway, young people, and even the not so young, will just be touched by something. Listening to Dr. King on the radio inspired me. Coming under the influence of Jim Lawson inspired me to think that I too could do something. You hear Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or meet him in person, or you hear Jim Lawson, you have a kind of executive session with yourself, and you say to yourself “John Lewis, you too can do something, you can make a contribution.” I didn’t like segregation, I didn’t like racial discrimination. And any tool or instrument they provided me with, I felt like I was imbued with something. So I hope that March will imbue people with something – the young, the very young, and those not so young, will be ready to go out there, and push and pull.

ComicsAlliance: The portrayal of the people around you in your early years is very strong, but specifically your parents. It was something that stood out to me because my parents were born in the south in the early ‘40s as well. And my mother specifically had a mindset that was very similar to your parents'. There were certain things that she just didn’t want to talk about, and your mother’s words, actions and body language reminded me of my own in a way. And now Nate Powell has taken these stories and captured them visually, recreating important moments in your early life and portraying the same mannerisms and facial features of these important figures at the time. What was it like seeing these pages come in with these action figures, as you put it earlier? What kind of emotions does that stir?

Congressman Lewis: It’s very moving. It reminds me of the actual reaction of my mother and my father. And I went through a period there where the people in the movement became more of a family than my own mother and father. It was difficult, because I felt like the people within the national movement became my brothers and sisters, and the older people, like a Jim Lawson or a C.T. Vivian or a Kelly Miller Smith, these ministers and others, these adults, became like my shepherds, my protectors, my teachers, because they were teaching me. And for a while I felt very cut off from my family, I felt like they didn’t understand. But I couldn’t disown them, they were my mother and my father. And much later on, they got the message. They had to go through a process, and they understood.

ComicsAlliance: I think Nate captures that incredibly well. After you meet with Dr. King for the first time to discuss attending Troy State, where no black students were allowed, as you’re on your way home in the car with your father, you talk about not speaking for the entire ride. And the next morning they ask you about the meeting, and they tell you they don’t want to be involved in all of that, for fear of your safety, theirs, and your community's. It’s about a six or seven panel page, and it works so well in part because Nate never shows their faces. You just see them from the back or in shadow, and I think that really captures the tension of the moment well. How did you feel about the handling of that scene, visually?

Congressman Lewis: I just think it’s perfect, really. I think what Nate did is perfect. I went back home when school was out, and I worked with them, I went to the field and talked to them about what was going on, what I was involved in, the sit ins, the freedom rides. I talked to my younger brothers and sisters about it. I think my father sort of broke the right way much earlier than my mother, and later on, by the time of Selma and the right to vote, she was all the way over. But it took time, it had to grow on them.

ComicsAlliance: Nate Powell is from the south as well, and he spoke at Comic-Con about that, and how he felt even more connected to the story because of that, and how it affected all the research he did. How much of that aspect of his upbringing did you see influence his work?

Andrew Aydin: As we worked with Nate, there was a common language. I think sometimes we talk about people speaking English or another language. But when your from the south, you speak – there’s kind of an understanding. And Nate got it. Nate knew it. There were things that we didn’t have to say, he just knew. And that made this collaboration so much better. It was really one of those things that you couldn’t identify going into, but once you got into it, and you sort of felt it happening, it really was one of those things that made it so much easier to make it all real, and add that extra depth. He understood what we were talking about, and in a lot of ways, he added things far beyond what we even could have considered, because he knew where and when and what we were talking about.

ComicsAlliance: You open the book with a flashback scene of the Selma to Montgomery marches. That’s a few pages, and then it flashes to you waking up on the morning of President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009. Those are obviously two of the most significant moments in this country’s history. But before going to that, we see you in your office with a woman and two young children, and you’re telling your story to them. They’re very young and obviously not very familiar with who you are, but she wants them to be. What drove the choice to tell the story through them, at least early on in the book?

Congressman Lewis: Well I think it was very important to look ahead, and include the very young. It was the children in Birmingham, it was the children in Albany, Georgia, it was the children in Selma. They did it. They played a role. So if the young people get it, if the young people understand what happened, how it happened and why it happened, they can influence the adults. In Birmingham and in Selma, you had kids saying they weren’t old enough to register to vote, but they wanted to do something. We did the same thing as students. We’d say “we sat in for you, now stand out for us. Register to vote.” Sometimes it takes the little kids to lead them. So it was important for these kids, these young children to understand what had happened. So we sort of hit it there. And I see part of my role, not just as a congressperson, but as someone who participated in the movement, and just as a simple human being, to do what I can to help educate another person to become committed to the way of peace, love and nonviolence.

Andrew Aydin: There’s a lot of meaning behind that, you know? I’ll try to go through the different layers. First, to put it in context, we came up with the idea in summer of 2008, and then he and I go through inauguration day together. All day he’s telling me stories, and I’m sitting there thinking “Why am I the only person who’s experiencing all of this?” [Laughs]. Everybody should see what it was like for John Lewis on that day. As he recounts those stories, there’s a moment in the script where he says “I appreciate you guys going through all this trouble, but there was two feet of snow on the ground the day we first sat in,” and he really said that! Because we were fussing over him. That’s how he ended up with the scarf you see him get.

Congressman Lewis: If you remember that day, it was so cold…

ComicsAlliance: Oh man, I was there. That was the coldest I’ve ever been.

Congressman Lewis: Oh, it was the coldest day of my life.

Andrew Aydin: And to have it be a single mother he was talking to, and her two children, they represent so much more than just themselves. Because I see kids and their parents come into the office all the time, and the congressman gives them more time than anybody. A lobbyist comes in and they can be out of the door in five minutes, but a child comes in with their parents and the congressman will give them a half hour, or an hour, because he knows they are what’s important. I think the decision to have it be a single mother was somewhat influenced by the fact that I was raised by a single mother. She used to take me on all these trips, you know. She’d save a little money, we’d pack up the car and do what we can, and she would take me on trips to teach me these things. And there are so many parents out there who are struggling to do that, and that’s a responsibility, and something that needs to happen, so that these kids grow and are educated, and inspired. Their names, Jacob and Esau, were used because the congressman’s office manager is named Jacob and he has a twin brother named Esau, and Jacob was incredibly helpful in this whole process, and it was sort of an homage to him. And there’s just a lot of layers to that part of the storyline, and it just seemed to fit, as we looked at it. We tried to combine a lot of pieces in there, with those three characters, and then lead that into the true non-fiction of what happened that day. And then the broader point of using Inauguration Day as an example, it wasn’t just because I wanted to share that experience I’d had with the congressman. There should be a marker placed on that day, because generations from now people will forget what that meant. They’ll be raised not remembering what it was like before we had our first black president. So hopefully this will in some way not just help people look forward, but help those in the future be able to look backward, and remember where we were then and how long that took, how much that took, and what the opportunities we have today mean and they open up for all of us.

ComicsAlliance: I think that’s one of the things that makes this book so important. As a kid, there were times when I would go through some sort of issue that was very clearly racially charged, and I’d become upset. But later on I’d think “this is nothing compared to what my parents went through.” At the same time, the struggle continues.

Congressman Lewis: Yes.

ComicsAlliance: You look back and you think Emmet Till was a long time ago, but then you realize Trayvon Martin was yesterday. So, again, so much of this is about you trying to reach out to younger people, and I think comics are an excellent educational tool, as you learned when you first came across The Montgomery Story. During this process, did you come to learn or appreciate more about how comics can be used to educate or inspire?

Congressman Lewis: Each time I pick up the book, or read something, or see a drawing, it convinces me more and more that this was the way to go. Comics, in a sense, the style, the images, it’s almost like music. They say music is a universal language, but when the eyes behold something, a figure, somebody moving; it’s real, and it cannot be denied. When you see or hear a word or a phrase here and there, it can be interpreted one way or the other, but when you see the actual drawing, it says more than anything else.

ComicsAlliance: Andrew, this is obviously your world, but did either of you, when you decided to embark on this journey – and after five years, I feel comfortable calling this a journey…

Congressman Lewis: Five years is a long time. That’s longer than a presidential term. [Laughs]

ComicsAlliance: It really is a long time. But when you started, did you seek out other biographical comics for any kind of inspiration, or to just see what you could and couldn’t do?

Andrew Aydin: Absolutely. We read Persepolis and Maus. Top Shelf had really jumped out to me, early on in the process, because they’re sort of the masters of this, in a consistent way. So a lot of the Jeffrey Brown stuff, Blankets, all of these were incredibly influential, but I would say Maus was probably the most influential. You can compare the framing devices, or the historical comparison of dealing with two brutal parts of our past. I think the moment in time when Maus came out was different from the moment in time when March came out, and I think maybe Maus just couldn’t handle non-fiction in quite the same way. The public just wasn’t ready for it. But Spiegelman and so many other people opened these doors that allowed us to be able to handle it in this way, and make this an acceptable thing to do.

ComicsAlliance: Congressman, we spoke for a little bit at Comic Con, and as we were doing so a woman you didn’t know just comes up to you and hugs you, just to say thanks, and it occurred to me that’s likely something that happens a lot. As you're traveling to promote this book, and you’re meeting different people, do you find that the connections you make with people as you hand them this comic are maybe different from the ones you make when you’re discussing things of a political nature, promoting another book, or all the dozens of other reasons you go out publicly?

Congressman Lewis: Oh I think so. You have individuals who come up to me and say “Oh, I’m so glad, I’m so proud, and I’m so pleased that you’re using this medium to reach people.” I heard it with librarians and parents, who said things like “Black boys need to read March. I need to get this for my nephew,” or “I need to get this for my grandson,” or something like that. “They need to read this, they’d love this.” That’s very gratifying, to hear people say things like that.

ComicsAlliance: If you’re handing this book to a kid who doesn’t know who you are, who doesn’t know your story, or maybe doesn’t really know the story of the Civil Rights Movement at all, what do you say to her or him?

Congressman Lewis: I would say, “Young lady or young man, read the book, but let me say something to you. I first heard of Rosa Parks when I was 15. I heard of Martin Luther King Jr. I met Rosa Parks when I was 17, I met Martin Luther King Jr. when I was 18, and that involved me in the Civil Rights movement. I grew up at a time when there were signs that said ‘white men’ and ‘colored men,’ or ‘white women’ and ‘colored women,’ and this book, this graphic novel, is the story of a struggle of many people, to change America, to make America better. I hope you will use this book to guide you through your life, for many years to come.” I would say something like that.

More From ComicsAlliance

![Brilliant Art, Tremendous Stories and Daring Creators: The 2016 Eisner Award Winners [SDCC 2016]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/07/eisner2016.jpg?w=980&q=75)