Ask Chris #96: Why Spider-Man Is The Best Character Ever (Yes, Even Better Than Batman)

Here at ComicsAlliance, we value our readership and are always open to what the masses of Internet readers have to say. That's why every week, Senior Writer Chris Sims puts his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

Q: When rating heroes you put Spider-Man above Batman but you write way more about Batman. Doesn't Spider-Man have as much depth? -- @ilionblaze

A: Don't get me wrong: Batman is my favorite character. As the last 95 installments of this column will attest, I probably spend more time thinking about Batman and how he works and what he means than anything else. Just going off of personal preference, I love Batman more than... well, more than most other things in the world, period.

Spider-Man just happens to objectively be the single greatest comic book character ever created.They actually make a pretty good contrast to each other, and it all starts with the idea that Batman is very much a child's fantasy. That's not a bad thing, either.

Every now and then someone will ask me just why it is that I like Batman so much, and the best way I can put it is that there's this pure, beautiful idea at the center of his character. Bruce Wayne has this perfect life until crime takes it away from him, so he decides right there that he's going to end Crime by himself. The fact that he's a child when this happens is a crucial part of the story, because if he was older, he'd realize the inherent flaw in that plan. He'd understand that the world isn't a fair place, and that sometimes bad things happen to good people for no reason, and that there's not much anyone can do about it. Only a child would think it was possible for one man to end crime, but because he's a child, that's exactly what he decides to do.

And the best thing is, he does it! A lot of people show Gotham as this crime-ridden urban nightmare, but as far as I'm concerned, there's no one getting mugged in Gotham City. There's no carjacking or guys robbing banks with shotguns. Why? Because Batman showed up and ended that. It's the reason that scene in Year One where he tells the gangsters that they're done is such a great moment, because he's right. There's no more room for them in Gotham City, because what you and I know as Crime here in the real world can't stand up against Batman.

If Crime's going to survive against Batman -- and it does, because if it doesn't, we don't have any more Batman stories -- it has to become something else, which is exactly what happens. People don't get mugged in Gotham City, they get mind-controlled by the Mad Hatter or dosed with Joker Venom or thrown into an elaborate deathtrap. Nobody robs a gas station, because they're too busy going after the priceless Egyptian Twin Cat statues at the museum. Crime in Gotham City operates on a whole other level than anything we'd recognize.

And it's like that because one child had the determination to forge himself into a weapon against evil. It's a beautiful, beautiful idea, and I will never not love that. But it's also a childish one, largely because he conveniently had everything he'd need to accomplish it, like being naturally athletic and handsome and having a photographic memory and a billion dollars and a mansion full of secret passageways and a butler.

Alfred might actually be the single best example of how much of a child's fantasy Batman really is. He's a parental figure who specializes in patching up his scrapes and bruises and making his favorite dinner, but Batman's actually his boss, which means that he can stay up as late as he wants and he doesn't have to wash behind his ears if he doesn't want to, so there. The only thing that even comes close to that is Captain Marvel Shazam Captain Marvel, a little kid who can turn himself into the kind of all-powerful being that every kid imagines grown-ups are, and then does all the stuff that kids want to do. He flies around, thumps a sneering bully on the head, and then makes friends with a talking tiger.

And again, that's not a flaw in those concepts. You can still use them as the core of very, very sophisticated and entertaining stories, for an audience of any age. That adaptability is one of Batman's greatest strengths as a character, but at their heart, Batman and Captain Marvel and Superman are what kids imagine adults to be, and the kind of adults kids want to be.

Spider-Man is different.

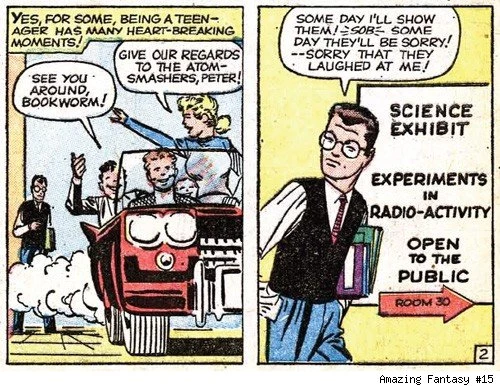

If Batman is a child's fantasy, then Spider-Man is very much rooted in being a teenager. When we're first introduced to Peter Parker in Amazing Fantasy #15, he's an outsider who feels isolated from everyone around him. He's miserable and resentful, but not because of some sort of defining tragedy, but because that's how you feel when you're a teenager. When he gets the one thing he wants -- the power that makes him stronger, faster and more popular than anyone else -- he promptly screws up and loses one of the only people that truly cared about him.

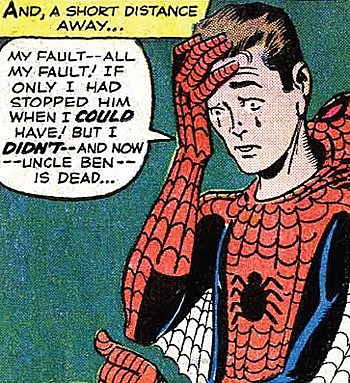

It doesn't really read like a super-hero origin, or at least, not one that you would've expected in 1962. There's no triumph, no Batman posing on the rooftop, no Superman performing herculean feats, not even a vow to use his powers to benefit mankind like you got with the Fantastic Four. Instead, the last panel of Spider-Man's first appearance is a teenager walking alone down a dark street, crying because his uncle died and it's all his fault.

It's actually structured less like a super-hero story and more like a horror comic, right down to the ironic twist ending and the fact that it has a moral. The only thing that really separates it from the kind of story you would've found ten years earlier in Tales From the Crypt is that Peter Parker comes back for more stories.

But he never really loses that edge of tragedy, and a big piece of that comes from the fact that Spider-Man's story doesn't romanticize the death of his parents in the ways that other heroes' stories do. Superman, for example, is an orphan, but the death of Jor-El and Lara doesn't really matter in the grand scheme of things; he even gets a second set. The death of Batman's parents is a tragedy, and it has to be horrible in order to be the catalyst for what sends him on the path to spending his entire life fighting crime, but it's also something that frees him. It's what gives him his fortune, and gets him out of school so that he can travel the world learning to be awesome. It frees him from family responsibilities, at least until he's ready to start building his own family as an adult.

Batman's family dies, but he bounces back. There was nothing he could've done to stop them from being killed -- again, because he was a kid -- so he makes himself into someone that could, and does it for others instead.

Spider-Man never gets over it. He never goes back to life as it was before Uncle Ben died. There was something he could've done to stop it, but he chose not to. Now, he does anything and everything he can to keep it from happening to anyone else. It's an atonement, but no matter what he does, it'll never be enough. He's not determined, he's driven.

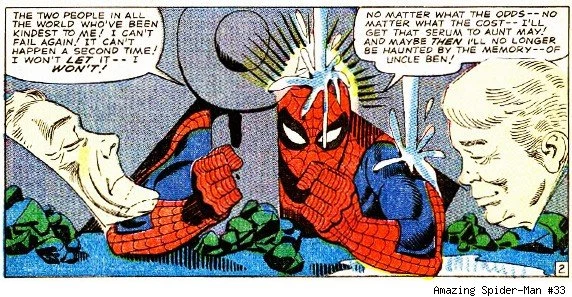

No matter what happens, no matter what it costs him, Peter Parker's going to help people to the best of his abilities, because he knows the price of not doing it. I'm not one of the extremely vocal fans of Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz's Spider-Girl series, but there's one aspect of it that they nailed: Peter Parker gets his leg blown off and can't be Spider-Man anymore, so he becomes a police scientist instead. He never stops helping people and protecting them, because he can't. There's no quit in him. Action is his reward.

It's also another aspect of Spider-Man as a teenage fantasy, too. Peter Parker can never get over that death, because when you're a teenager, nothing ever feels like you'll get over it. Everything is important, everything's the end of the world. And those ideas come together particularly well in the character of Aunt May.

You'd think Spider-Man would be lucky to still have one of his parental figures, and on one level, he is. But on another level, he's burdened by it. He's not only the reason that Aunt May was left alone when Uncle Ben died, he's also suffering from the fear that he'll lose her, too. I once wrote that the genius of Batman's parents dying was that it was a fear that almost everyone can relate to on a primal level, but Spider-Man goes one step beyond because for him, it could happen all over again.

And just like before, it could be his fault. That gimmick in the early days where Aunt May would die of fright if she ever found out Peter was Spider-Man might seem a little heavy-handed, but it's brilliant in that it sets up an impossible choice. If he keeps being Spider-Man, he could lose Aunt May just by the act of existing, but if he doesn't keep being Spider-Man, people get hurt that he could've saved.

So he has to be Spider-Man, because he knows for a fact that he can help people, and that fact makes the decision for him. It's another piece of that sacrifice, that atonement, but it's also an incredible illustration of the pressure that he's under, and how he just has to carry on, dealing with the things that he can control.

And how does he do it? By creating a better version of himself.

Batman's essentially Batman from the moment his parents die, he just needs to go learn kung fu and how to be a detective. But at the start of Peter Parker's story, he's not a hero -- he's not even close. He's shy and he's an outcast, and while those things aren't really his fault, they lead him to become pretty vindictive:

He's arrogant, too. When he builds his web-shooters, his boasting is downright super-villainous:

He's vain. He's shallow. He only wants to benefit himself, so he uses these phenomenal abilities he's gotten to go on TV and do tricks for an audience.

When Uncle Ben dies, he pays for all that and sets off on a mission to do better -- and part of that is that he basically starts pretending to be this quick-witted, fast-talking hero who was the complete opposite of his own personality. It's worth noting that one of the very first plot points in the series was that Flash Thompson, the bully who hated Peter Parker, was literally the president of Spider-Man's fan club. Even today, there's a recurring idea among Peter's friends that you can't rely on him for anything, but Spider-Man's always there to save someone who needs it.

Peter Parker has too much guilt, too much responsibility, too much to worry about with Aunt May's health, no money and a scholarship that he's hanging onto by a thread. Peter couldn't handle the pressure that he was under, so he created someone who could. He creates the kind of person who would've stopped that robber before he killed Uncle Ben. The kind of person who can crack jokes under pressure, because he's so confident that he can conquer his problems that they're just something to make fun of. He creates Spider-Man to be the person he wants to be.

Even the name points to that idea. Peter's young when he gets his powers, but he gives himself an adult's name. He's a boy pretending to be a man, but over the years, we watch as he becomes that better person for real. Because that's what you do when you're a teenager -- you start figuring out who it is that you want to be, and you start to become that person.

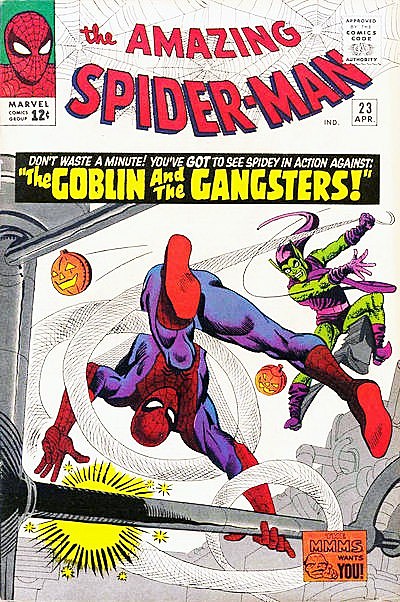

But at the same time, you don't really relate to adults. There's this sort of mutual mistrust between the generations, and Spider-Man reflects that beautifully. Adults aren't aspirational figures for Spider-Man, they're adversaries. They're the teachers who can turn on you and make your life miserable with a bad grade.

They're the scientists who created atomic weapons and led you to spend the next 50 years getting taught how to duck and cover in the event of a nuclear war.

They're your friends' parents, who seem nice but end up hating your guts for reasons you'll never really understand.

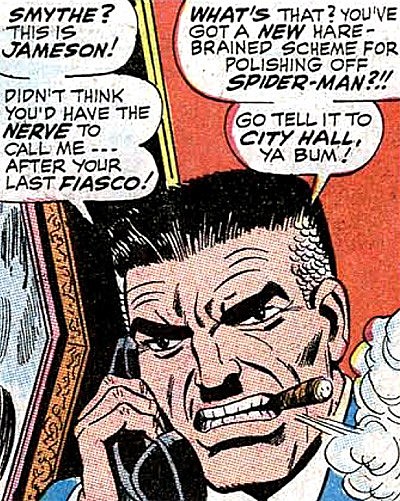

They're the adults that seem to just hate you for no other reason than you're young, even when you try to do the right thing.

Those first 200 issues of Amazing Spider-Man -- a run that's downright shocking in how good it is -- are essentially teenager problems on a super-heroic scale, both literally and translated into the metaphor of the super-hero adventure story. It was done so well that it was a blueprint for virtually everything that came after, in the same way that Fantastic Four #50 was a blueprint for the Big Event. If you've read Invincible, or Nova, or Blue Beetle or Darkhawk, or Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or any of a hundred others, then you've seen that blueprint dusted off and adapted. Those things exist because of Spider-Man.

That said, there's nothing that's inherently better about a "teenage fantasy" as opposed to a "childish" fantasy. They're both great in their own ways, and they can both be bad in their own ways, too. What it really comes down to, though, is the message. The kind of fantasy that you get with Spider-Man allows you to deal with a message that's a little more complex, and over the past 50 years, that's exactly what the people who work on those books have done.

I'm a firm believer in the idea that super-heroes teach you things, and it's usually a pretty simple lesson. Superman teaches you to be nice and to be a good person, because that's the way you make things better for everyone. Batman teaches you that if you're determined enough, and if you try your hardest, one man can change the world. Those are great guidelines, not just for storytelling, but for life.

But Spider-Man's lesson is a little less sugar-coated, and a little more human.

Spider-Man teaches you that you're going to screw up. It's going to happen, and it's going to be bad. You're going to make bad decisions and it's going to feel like they're going to crush you. It's going to hurt.

But Spider-Man also teaches you that the only way to get through it is that you never, ever quit. It's not easy, but even if it seems impossible, you can beat anything that stands in your way. You can become the person you want to be.

That's why he's the best.

That's all we have for this week, but if you've got a question you'd like to see Chris tackle in a future column, just send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #AskChris, or send an email to comicsalliance@gmail.com with [Ask Chris] in the subject line!

More From ComicsAlliance