Ask Chris #92: The Great and Terrible ‘Batman: Year Two’

Here at ComicsAlliance, we value our readership and are always open to what the masses of Internet readers have to say. That's why every week, Senior Writer Chris Sims puts his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

Q: Why am I so wrong for hating Batman: Year Two? -- @BatIssues

A: No joke, guys: As bad as its reputation might be, Batman: Year Two has a special place in my heart. If I'm honest -- and the Ask Chris column is nothing if not a sacred bastion of truth in an uncaring world -- Year Two's easily in my top ten favorite Batman stories ever, and might even have a shot at cracking the top five. I love that comic.

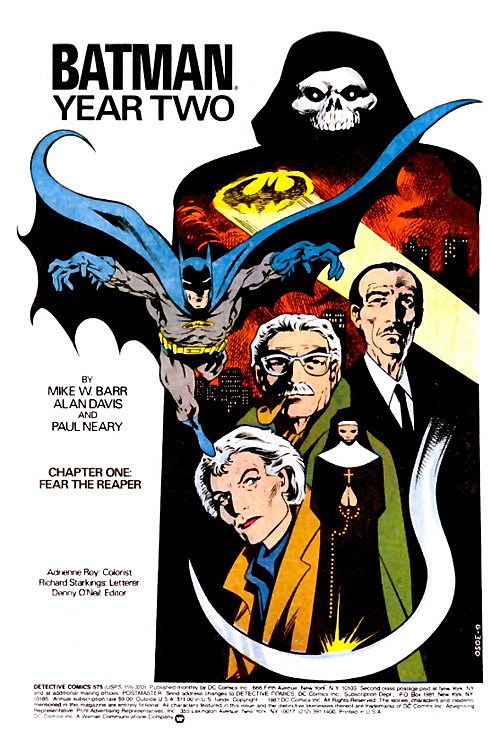

I mean, don't get me wrong. I love it, but it's also absolutely terrible. It's not like the people behind it weren't talented, though. Just on the art side, you had Alan Davis and Paul Neary doing the first issue in the usual beautiful style they bring to their books that makes me wish they'd done way more Batman work than they did. Of course, while the fact that they replaced on a four-part story after one issue probably wasn't a good sign for readers back in 1987, Davis's replacement on pencils, a hot new artist named Todd McFarlane did pretty well for himself. In fact, as much as he'd make his name the following year when he got the gig on Amazing Spider-Man, Year Two still stands as my favorite McFarlane work. To be fair, though, I've never read an issue of Spawn.

It's not like the people behind it weren't talented, though. Just on the art side, you had Alan Davis and Paul Neary doing the first issue in the usual beautiful style they bring to their books that makes me wish they'd done way more Batman work than they did. Of course, while the fact that they replaced on a four-part story after one issue probably wasn't a good sign for readers back in 1987, Davis's replacement on pencils, a hot new artist named Todd McFarlane did pretty well for himself. In fact, as much as he'd make his name the following year when he got the gig on Amazing Spider-Man, Year Two still stands as my favorite McFarlane work. To be fair, though, I've never read an issue of Spawn.

And then there was Mike W. Barr, who's right up there with Bill Finger as one of the most underrated Batman writers in the history of the character.

His run on Detective in the late '80s is just one classic after another, with beautifully crafted issues like #571's "Fear For Sale" and the big anniversary bash in #572 that saw Batman teaming up with Slam Bradley, the Elongated Man and Sherlock Holmes to solve a world-spanning mystery. He even wrote the single best attempt at the deceptively tough task of creating an "evil Batman" in "The Player on the Other Side" from Batman Special #1. If you haven't read it, it's a kid whose criminal parents are gunned down by cops on the same day that Thomas and Martha Wayne are killed, who swears to fight against the law and wears a big W on his face with ends that stick up and look like Batman's ears. It sounds goofy, and a lot of it is, but Barr and artist Michael Golden pull it off.

Of course, he also wrote Batman and the Outsiders and set DC down the path of trying to convince people that Geo-Force was not just awful for the next 20 years, but those are sins to be addressed in another column.

And yet, you never really hear people talking about the year Mike W. Barr spent writing Batman stories, and there's a reason for that. See, while Barr was writing classic, accessible adventure stories with artists like Alan Davis and Jim Baikie in Detective Comics, Frank Miller and Dave Mazzucchelli were over in Batman essentially redefining the character with Year One. It doesn't really matter if you're doing great Batman stories, when someone else is doing what was regarded as probably being the best Batman story ever printed, you're going to get overshadowed.

But that also leads to one of the more interesting things about Barr's run. He wrote Detective from December of 1986 to December of 1987, coming hot on the heels of DC's first big shot at flipping over the table and starting over with Crisis on Infinite Earths. This was the year where everything had the potential to be exciting and new, with a new origin stories for Superman and Batman, an all-new Justice League with a new direction that combined modern sitcom sensibilities with super-heroic action, and Wonder Woman was getting ready to make her big return. It was an undeniably exciting time, but while a lot of people were focused on discarding the past, Barr was taking the stuff they'd just gotten rid of and bringing it back.

His entire run on Batman was built on modernizing classic elements of Batman's history, both in content and in form. While everyone else was trying to make their stories look modern, Barr and Davis revived the classic Golden and Silver-Age style title pages for their stories:

And he didn't stop at the title page either. His stories saw the revival of characters like Paul Sloane (the second Two-Face) and the Crime Doctor, both of whom had been created in 1943. The anniversary team-up I mentioned is structured like a Silver Age story -- Sherlock Holmes shows up and explains that top shelf honey and "rarified Tibetan air" have allowed him to live to the age of 140 -- and even Batman and the Outsiders saw the revival of Metamorpho and Black Lightning, two characters that had fallen into obscurity. But it's a testament to his skill that these stories don't read like throwbacks. They read like modern stories that use those old elements to do something new.

But at the same time, there are pieces of Barr's Batman work that are just... off. I'm not sure if it was Barr's attempt at drawing on those very first stories back in 1939, but his Batman has what could charitably be referred to as a pretty callous disregard for life.

One of the most blatant examples comes from the bat-sh*t crazy "Messiah of the Crimson Sun" from 1982's Batman Annual #8, a tribute to the equally bat-sh*t crazy '50s sci-fi era of Batman stories. The plot is that Ra's al-Ghul has a space station with a solar-powered death ray that he's used to get people to worship him as a cult leader, and when Batman and Robin head up to space to stop him, Batman ends up casually using a tractor beam to pull Ra's's escape pod into the beam, vaporizing him and then watching as his ashes drift off into the vacuum.

Despite Batman's smarmy dismissal of Robin in that last panel, he has no reason to think that he didn't just kill Ra's al-Ghul as thoroughly as humanly possible. His ashes float into space, guys.

But to be fair, if you stretch your Bat-morality as far as you can, you can justify that. After all, Ra's al-Ghul's entire deal is that he's an immortal who comes back from the dead, so Batman has no reason to think he's actually killed Ra's al-Ghul either -- and as it turned out, he hadn't. Comics, everybody.

The problem is that this isn't an isolated incident in Barr's work. Even that Silver Agey detective story that I like so much has Batman using a criminal as a human shield.

Like I said, Barr's an all-time favorite, but if that's not a red flag, I don't know what is.

And at long last, that brings us to Year Two, where those three elements -- the eye towards modernizing the past in the wake of Crisis, the looser morality, and the overwhelming success of Year One -- come crashing together for a story that's as fundamentally broken as it is bizarre, and one that I can't help but love in spite of itself.

Like most of Barr's scripts, it starts out with a phenomenally good and deceptively simple idea. In this case, it's an idea that springs right out of the fact that 45 years of Gotham City History had just been wiped out, leaving a clean slate to play with. So the simple idea is this: What if there was a vigilante in Gotham City before Batman?

Say hello to the Reaper:

Despite cribbing a catchphrase from Blue Oyster Cult and saying it around eight thousand times over the course of the next four issues, I love the idea behind the Reaper. He's essentially a "modernized" version of Batman, tougher and stronger, with a costume that's even more demonic and terrifying. Most important, though, was the fact that he was a killer.

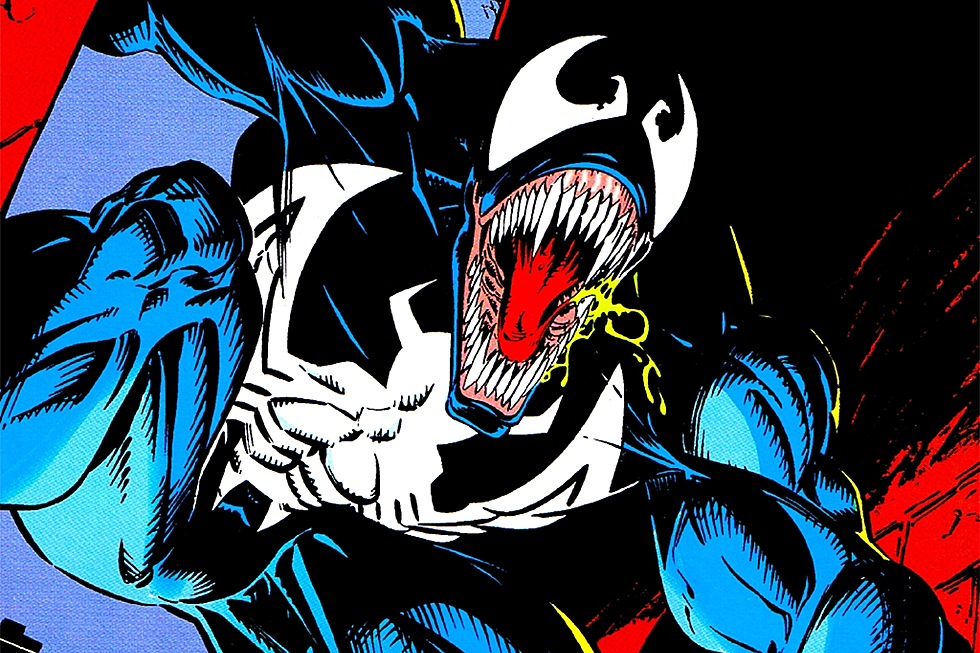

In that respect, it's hard to look at the Reaper as anything other than Barr's response to a character that had just exploded into popularity over at Marvel the previous year with a limited series that was successful enough to warrant an extra issue and an ongoing title that hit shelves the month after Year Two started. Davis's design for the character even used the same iconic skull imagery.

In other words, Year Two basically starts out as Batman against the Punisher.

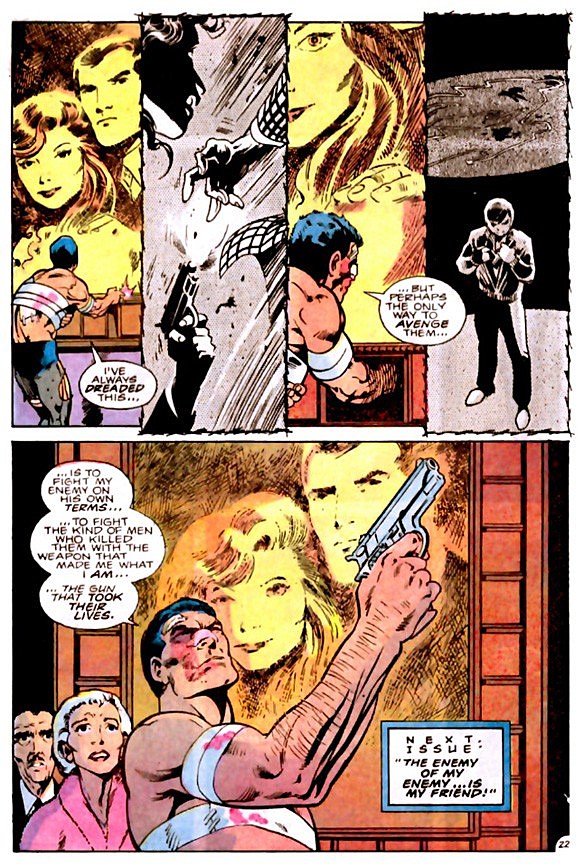

Even the Reaper's origin, revealed later in the story, is designed to mirror both Frank Castle's and Bruce Wayne's in equal measure:

The difference is that his daughter lives, but we'll get back to that in a minute.

What matters is that this is an idea with so much potential. Not just to act as a childish "Batman could so beat the Punisher!" refutation of the conversation that was going on in comic shops across the country, but to explore what Batman means to his world. The fact that there was someone who was stronger, tougher, and willing to go further who still couldn't save Gotham City from becoming so bad that its most prominent citizens were gunned down in an alley says so much about why Batman has to operate the way that he does. It makes him unique, even among people who followed the same sort of path.

But while Barr, Davis and McFarlane flirt with that idea, it never really pays off. Instead, the Reaper's return to action leads him into a conflict with Batman, where a guy quite literally old enough to be his father hands the Dark Knight his ass in a fistfight. The Reaper walks away without a scratch thanks to his +4 Studded Leather Armor, but Batman is beat up, cut down and shot at by the Reaper and his gun-swords -- by the way, he has gun-swords -- and then crawls through a sewer to have a crisis of confidence.

This is where things start to get a little shaky, because while I'll readily accept the idea that Batman wasn't used to defeat, being stabbed and shot at sort of seems like something he should be used to by his second year as a crimefighter in a world where he routinely faces acid-murder at the hands of a homicidal clown. But for the sake of drama, sure.

And then it goes right off the rails.

Just so we're all clear on this: That is a page where Batman takes the gun that killed his parents, which he apparently stole from the crime scene, out of its secret hiding place and says that using it to shoot someone is the only way to avenge them. I have a story where Batman dresses up as a gorilla because he went in a sensory deprivation chamber and hallucinated that Robin died on another planet, and this is still the craziest Goddamn thing I have ever seen in a Batman comic.

But at the same time, I kind of love it. The sheer unmitigated audacity of Barr and Davis here, not only giving Batman a gun, but the actual gun that shot his parents. It's a bold choice. Hell, it's probably the boldest choice that it's even possible to make in a Batman comic -- nothing else, not even Batman just straight up shooting someone, has that much symbolism all blowing up all at once.

Again, don't get me wrong: This should never have happened. Even in the context of a younger, less experienced Batman, it violates major rules set up within the psychology of the character, even if it does explain how the GCPD could never find the guy who did the shooting. But in that time, when the entire universe was bringing down sacred cows like a slaughterhouse -- Superman's not totally invulnerable! The Flash is dead! There's no multiverse! -- was there really a reason why it shouldn't have happened?

Well, yes. Yes there was. But you can sympathize with the desire to push those boundaries in ways that people had never seen.

The problem --or one of the problems, at least -- is that every part of this is so sensational that it tears the story away from the conflict between Batman and the Reaper and boots it straight down a path that's increasingly ludicrous. The Reaper plot is still there driving the action, but the focus shifts to the book becoming "what if Batman did a bunch of stuff that you never expected him to do because none of it makes any sense." And if the scene above is where the story goes off the rails, the end of Part 2 is where Barr comes back with a bulldozer and tears up the whole damn track:

Not only is the Reaper such a threat that Batman calls a truce and teams up with Crime (as represented by a short bald man in a bad suit), but then he TEAMS UP WITH THE MAN WHO KILLED HIS PARENTS. Who apparently has not bought a new hat in 25 years.

In no way whatsoever does this make sense, and it only gets worse when he and Chill hit the streets, acting more like the straight-laced cop and the loose cannon who doesn't play by the rules from any given late '80s buddy comedy than, say, an unrepentant murderer and the man that he traumatized so profoundly that he started spending every night of his life dressing as a giant bat and punching out escaped mental patients.

There's even a scene where Batman watches Joe Chill kill a man with a gunshot and lets him off with a Stern Warning:

And just in case this story wasn't ridiculous enough, Batman also gets engaged:

It turns out that his fiancee, Rae, is the Reaper's daughter, because of course she is. How could she be anything else?

Eventually, Barr revisits the classic Silver Age version of Batman confronting Joe Chill -- the moment that the entire series was building to from the moment the gun showed up. It's actually a really great scene, with Batman taking him to the boarded-up movie theater in Crime Alley. Rather than sending him freaking out and running into traffic for a tidy, not-my-fault bit of manslaughter like he did in the original version, though, Batman holds the gun to his head, ready to pull the trigger. But he hesitates, and that's when the Reaper shows up and shoots Chill in the head for him.

The reasoning here is sketchy at best, but the gist of it is that the Reaper thinks Batman is weak because he's not really willing to kill. Then they fight on the construction site of Wayne Tower -- which, hilariously enough, is being built across the street from Crime Alley -- and the Reaper decides that Batman is a killer after all, and then jumps to his own death. Then Batman puts the gun into the foundation of Wayne Tower and calls it a night. Then Rachel joins a convent. The End. Sort of.

I have no idea how the Reaper arrived at his conclusion and why he allowed himself to fall, but at this point in the story, it hardly even matters anymore. Things like motivation and logic have been tossed out the window two issues ago in favor of a roller coaster ride of sheer kookiness.

But while I don't like what happens in the story one bit, I still can't help but respect that about how it's told. Barr, Davis and McFarlane go all in at every opportunity. They're given a universe that, for the first time in forty years, was suddenly almost entirely fluid. Nothing was locked in, and they took advantage of that, telling a story where you honestly never knew what was going to happen next because it was built to shatter your expectations.

And in 1987, those expectations were already so fragile that they had to be an irresistible target. After all, DC had just spent a year telling people stuff like "Supergirl doesn't exist," so who was to say that the new Batman wouldn't be a new-style gun-toting anti-hero? At the time, it was just as likely that young Bruce pocketing Joe Chill's gun would become an etched-in-stone part of Batman's origin as Miller and Mazzucchelli's famous pearls.

And in 1987, those expectations were already so fragile that they had to be an irresistible target. After all, DC had just spent a year telling people stuff like "Supergirl doesn't exist," so who was to say that the new Batman wouldn't be a new-style gun-toting anti-hero? At the time, it was just as likely that young Bruce pocketing Joe Chill's gun would become an etched-in-stone part of Batman's origin as Miller and Mazzucchelli's famous pearls.

It didn't, of course. Barr left 'Tec at the end of 1987 and went on to create the incredibly fun Maze Agency with Adam Hughes. By 1994, Year Two had excised from the Official Batman Continuity™ for obvious reasons, although it's worth noting that it took Barr's other major Batman masterpiece, the genuinely great Son of the Demon, with it.

But there are a couple of epilogues to this story, one of which is a literal epilogue -- or at least a sequel. So in 1991, Barr and Davis reunited for a story where Joe Chill's son became the new Reaper in order to avenge his father's death at the hands of Batman, going so far as to dig up the Wayne Tower foundation stone so that he could use the same gun, because he secretly witnessed Chill Sr.'s death and saw where Batman put it. Fittingly enough, it's called Full Circle.

Despite its shortcomings, it's easy to see why there was enough positive response to warrant the sequel. Davis's art is beautiful, McFarlane's is dynamic, and Barr's story is certainly... thrilling. But more than that, it's full of great ideas. So great, in fact, that a lot of them were stripped out and repurposed for Batman: Mask of the Phantasm.

It's definitely not a straight adaptation -- you can tell because Mask of the Phantasm makes sense -- but Year Two was a clear influence on the film. The look and idea of the Phantasm, and even Andrea Beaumont's ill-fated romance with Bruce Wayne are lifted directly from the Reaper (although with a much better twist) and stripped of the non-stop goofiness of I must team up with the man and gun that shot my parents!, they work really well.

That's what it really comes down to for me. In the end, Year Two is fatally flawed in about sixteen different ways, but it's also a comic that has a genuine sense of excitement and shock to it that's this perfect synthesis of the weirdness of the late '80s and the lunacy of the '50s and '60s. The stuff that works works, and the stuff that doesn't is at least interesting. For good or ill, it's a book that operates entirely on saying "why not?" I can't not love that about it.

And hell, it's better than Year Three.

That's all we have for this week, but if you've got a question you'd like to see Chris tackle in a future column, just send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #AskChris, or send an email to chris@comicsalliance.com with [Ask Chris] in the subject line!

More From ComicsAlliance

![Civil War Correspondence: Ceasefire [Recapping ‘Civil War II’ #8]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/12/CWII-Featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![The First Ever All-New Avengers Are Back In ‘Avengers’ #1.1 [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/10/Avengers_1.1_Featured.jpg?w=980&q=75)