Batman Writer Alan Brennert, ‘Gotham’, And The Truth About DC Comics Media Royalties

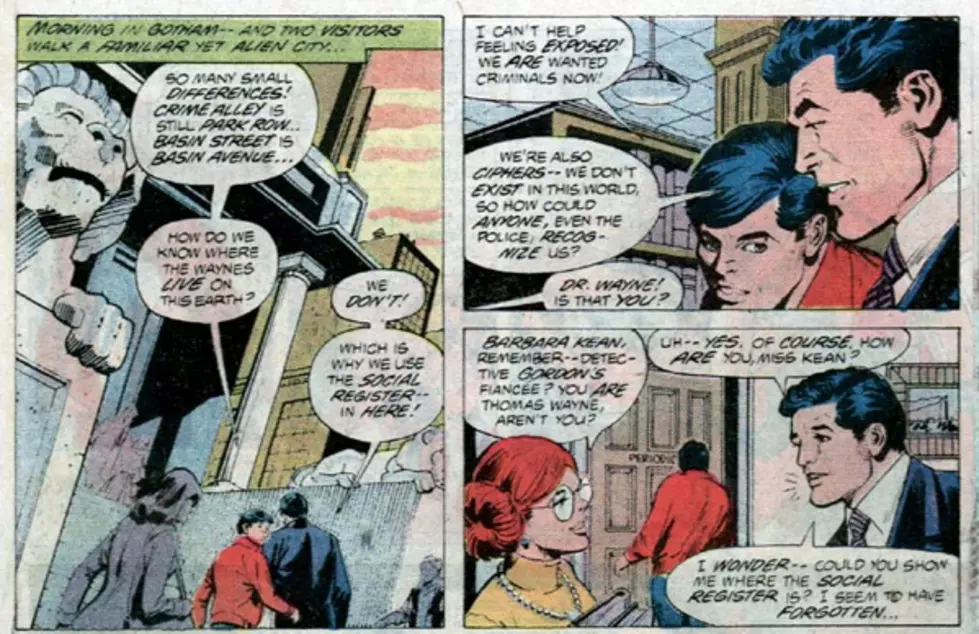

A favorite among many longtime and hardcore Batman fans, writer Alan Brennert released a statement on Facebook this week regarding his lack of compensation for the use of the character Barbara Kean Gordon in the upcoming Fox TV show Gotham, a live-action series based on the Batman characters. Brennert wrote a story in 1981 in which the character was introduced as the fiancée of then-Lt. James Gordon. While it was an out-of-continuity story, the character was later brought into canon as Commissioner Gordon’s wife (most notably in Batman: Year One, and in the films Batman Begins and The Dark Knight). In the Gotham television series' pilot episode -- as seen and verified by ComicsAlliance staff -- Barbara Kean is introduced as James Gordon's bride-to-be, played by Erin Richards.

For this reason, Brennert requested equity in the character and compensation for her use in Gotham – a request that has been denied, which has in turn inspired consternation among Brennert's fans, industry observers and other creators.

There's a lot to unpack in this important topic, but what we should first understand are the industry terms in play. Basically, at DC Comics “equity” -- known colloquially as royalties, even though royalties are a different thing altogether -- is a sum of money the creator gets whenever their character is used in TV, in merchandise, in film, etc. For some characters that may be a paltry sum (Brennert said he'd learned that his payout for Gotham would be $45 per episode) but for others it can be quite significant. These payments are for use of characters, as distinct from plots or storylines.

DC is known in the industry for being uncommonly judicious when compensating creators for their characters' appearances in other media. For example, Bane co-creator Graham Nolan has gone on the record about his equity payments from that character's presence in toys, animation and film since he and Chuck Dixon introduced him in the early '90s, and continue to enjoy payments related to The Dark Knight Rises. Similarly, writer Len Wein "has lived off bonuses for Lucius Fox in Batman animated fare and feature films," according to former DC Comics editor Bob Greenberger.

But in order to qualify for equity at all, certain conditions have to be met. This is a very important part of the compensation system at DC.

Brennert says the qualifications were described to him thus:

An executive at DC Entertainment—let’s call him “Johnny DC”—dismissed my request for “equity” (a percentage of income received when a character you create is used in other media) in the character. The justification? Because I had given her the same name, profession, and appearance as her daughter (at the time, just a sly wink to the reader), she was “derivative” of her daughter Barbara (Batgirl) Gordon and equity “is not generally granted” in derivative characters like wives, husbands, daughters, sons, etc., of existing characters: “this is the criteria by which all equity requests are measured.”

In his post about this matter, Brennert said that DC has given other creators such as Mark Waid equity in characters that are derived from existing DC characters. He said Waid receives equity for the character Impulse (Bart Allen), derived from Robert Kanigher, John Broome and Carmine Infantino's character Barry Allen, and as such, Brennert should be compensated similarly for Barbara Kean Gordon. (Waid's own statements confirm that he received equity for creating Bart, but in comments he says that he stopped receiving compensation, "[o]nce Bart abandoned the Impulse name for “Kid Flash".)

As a former DC editor, I'm well aware of the equity process. In the course of my job at the company, I was involved with sending the equity paperwork to creators, letting them know the guidelines, and occasionally submitting related paperwork to the proper department within DC to ensure the creators were taken care of. There were some characters from comics I worked on where creators requested equity and were turned down based on the above criteria, and Brennert is one of many such creators. There are lots of creators who have been granted equity when their characters do meet those qualifications.

Based on my experience, my reading of the situation is this: Brennert’s creation of Barbara Kean Gordon is not only "close" to her sometimes-daughter in the DCU, Barbara Gordon; it fits all of DC’s stated criteria for being officially derivative. She looks the same, has the same name – she’s even at a library after hours, implying that she, like Barbara Not-Kean Gordon, is a librarian.

These similarities are quite different from the character of Impulse, who has a different name, different appearance, different back-story, and a different superhero name than his grandfather, the Flash, aka Barry Allen. Impulse also had his own long-running and popular series.

The equity situation at DC is a case where you actually get points for originality, but the line is blurred (no speed pun intended) with the inclusion of a character like Impulse, and perhaps it is not always fair, but I'd argue it’s better that characters like Impulse earn their creators equity than drawing a hard line at every single character who could be considered even vaguely derivative. Brennert might think it’s a sly nod that both versions of Barbara Gordon look alike, but from a DC perspective, that is likely a big issue for granting equity.

There's another layer of confusion to the topic of comics creators and media exploitation, as explained by Mark Waid in a post from 2013:

The confusion about extra-media compensation arises in that Levitz, while he was DC’s publisher, made it a policy to cut respectable bonus checks to writers and artists, regardless of legal obligation, if elements from any of their stories (even work-for-hire ones) made it into outside media adaptations movies or TV shows. Did you like the scene in Batman Begins where young Bruce Wayne climbs a Himalayan mountain holding a blue flower? Christopher Priest got paid for having come up with that. Or the scene where Bruce Wayne picks out a potential Batmobile from among his own holdings? That was lifted from a Chuck Dixon-written comic, and Paul sent Dixon a check to acknowledge that. Same with dozens of similar moments in cartoons, DVDs, and so forth and so on. It wasn’t legally necessary, it was totally at Paul’s discretion and only Paul knows what math he used to determine what he felt would be fair, but it was a goodwill gesture from an exec sympathetic to the creative community.

And most critically, it wasn’t a written policy or guarantee. It was a courtesy.

Once Paul left, that courtesy was deemed no longer necessary by the executives and the policy was rolled back, as was DC’s absolute prerogative. Currently, DC pays bonuses only on material that’s a straight and highly faithful adaptation of existing work; for instance, Frank Miller (rightfully) got a check for the recent DARK KNIGHT RETURNS animated movies, but if the next animated film takes its plot from (say) BATGIRL: YEAR ONE but calls it “BATMAN: BATGIRL BEGINS” and adds anything to the story, Chuck Dixon and Marcos Martin will receive nothing. DC has removed itself from the complicated business of having to evaluate how much certain adapted elements are “worth” and instead simplified the system to “pay” or “don’t pay,” with “don’t pay” the default.

The situation Waid is discussing where creators got bonuses for story beats being used in other media is different from character equity. Character equity, when done properly, grants a creator financial compensation whenever their character is used, regardless of if the character is used in a story based on a plot they wrote. Pay for specific plot lines if it happens is based on the actual work-for-hire agreement and any bonuses beyond that are, as Waid says, at DC's discretion. Character equity requires additional paperwork, but once done and approved means any iteration of that specific character a creator made will lead to compensation for the creator.

Granting equity on characters based heavily on another creator’s work does seem potentially problematic. It might feel like it’s all just money coming out of the big DC/Warner Bros. pie, so who cares? But it’s also money earned on the backs of others’ creations, which is the very thing many people -- creators and readers -- are unhappy seeing in the work-for-hire agreements at companies like Marvel and DC. The money may not come out of other creators’ pockets, but it does send a complicated message. DC’s choice to stay out of such a potential mess is completely unsurprising, even if it has resulted in this controversy.

Creators’ rights is a hugely important issue, and there's no question writers and artists have been exploited throughout American comics history. Brennert admits the meager amount of money in play is not the issue for him; it's the principle, as he sees it. It’s unlikely DC will amend its equity rules for this situation, leaving Brennert as yet another cautionary tale for creators about protecting their rights.

More From ComicsAlliance