Unpacking the Transphobia in ‘Airboy’ #2

Airboy is a four-issue miniseries written by James Robinson and illustrated by Greg Hinkle, and published by Image Comics. Its premise is that Robinson and Hinkle, portrayed as fictionalized versions of themselves, are tapped to revamp an obscure Golden Age character. Robinson suffers writer's block, which hanging out with Hinkle doesn't help; the two of them wind up injecting, inhaling and eating the equivalent of a small pharmacy and go on a bender. When they awaken, they find that the creation they were tasked to revamp, Airboy, has sprung to four-color life, and he sees much wrong with the world – possibly rightly, possibly wrongly.

So far, so good. It's metafiction, but speaking as someone whose shelves groan under the weight of Grant Morrison and Terry Pratchett, there's nothing wrong with a good metafiction that blurs the line between creation and creator. But there's a dark side to blurring that line, and that dark side is that it makes it difficult to tell where the fictional character ends and the real person's opinions begin – and that's lent an odious air when the opinions ventured in the narrative are wrongheaded and harmful.

Spoiler Warning: the events of Airboy #1 and #2 are discussed herein. Content warning: transphobic scenes are chiefly discussed, and I use the word "genitals" a lot.

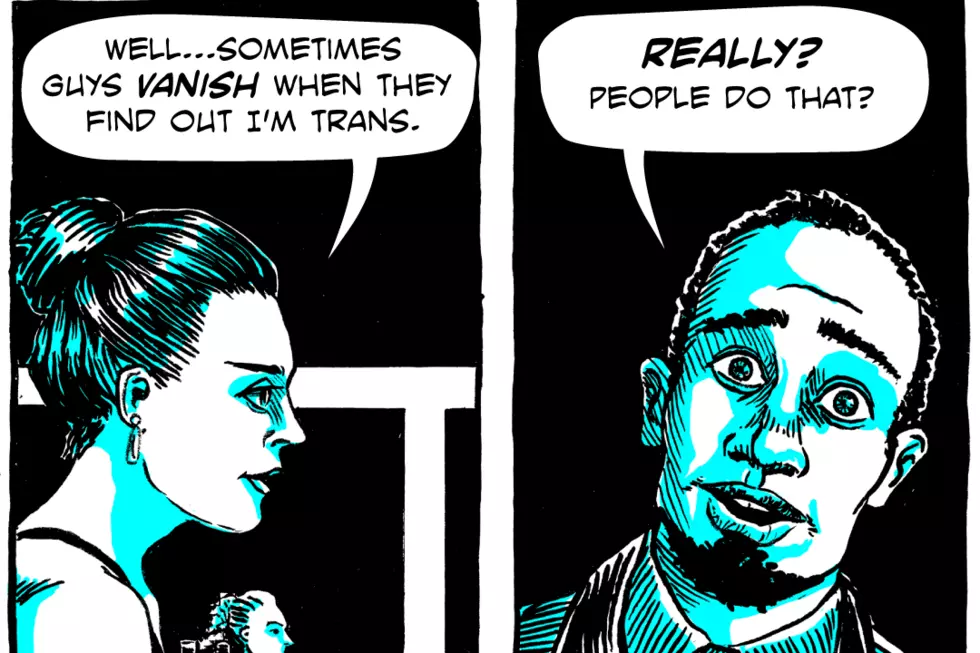

So, there are big problems here. To unpack them one by one, we start with the notion of "the trap." While Fictional James knows ahead of time that the woman he's with is transgender, Airboy doesn't. So while it's not a trap scenario in Fictional James' case, it is in Airboy's. Therefore, the notion of Airboy being "tricked" revolves around whether or not Airboy is real, and there's pretty strong evidence that he is real. He's a shared, persistent hallucination that addresses, and is addressed, by the pot dealer; he gets baked just as roundly as Fictional James and Fictional Greg do. But even if he's not real, a narrative can happen to an entirely fictional character and still be harmful and wrongheaded.

The notion of the trap is that a transgender person will somehow trick cisgender people into having sex with them before revealing they're pre-op/non-op transgender (as in, no genital reassignment surgery.) It is transphobic, because it inevitably feeds into the notion of transgender person as deceiver.

This idea that this entire group of people is being dishonest about what kind of sexual equipment they have casts a shadow over the entire transgender community and paints us all as liars. Liars about our genitals, liars about our identities, even liars to ourselves, with the idea that this transgender thing is all in our heads and therefore somehow invalid.

Lying, in our society, is considered to be a bad thing, even if there are times it's the least bad thing. If the notion is afoot that an entire group of people are liars, no good kind of moral stereotype can follow. All this, when the simple act of admitting to yourself that you're transgender, much less admitting the same to anyone else, is an act of honesty that can be bone-shakingly terrifying.

The "trap" is such a stereotype associated with transgender people that it's turned into a nickname people call us. It needs to go away. And instead of banishing it to the distant past, Airboy #2 has it as a fulcrum upon which Airboy's disdain for modernity turns.

Furthermore, during the confrontation between Airboy and Fictional James Robinson, Fictional James explains his side of the situation. To his credit, he mostly gets the pronouns of the transgender woman in question right, but muddles the issue when he answers both in the affirmative and the negative when Airboy asks if she was a man. He also uses the word "tranny" a lot.

On the subject of whether or not a transgender woman is a woman even if she's pre-op or non-op (the same going for transgender men and the various types of nonbinary and genderfluid identities), the answer is yes. Gender is a social construct. There are far more configurations of chromosomes than the XX and XY that high school biology simplifies the issue down to. Intersex people --- people born with genitals of an indeterminate state --- are 1 in 2,000. If you live in anything larger than a small town, there's statistically an intersex person living there. Sex has never been a clearly defined indicator of gender, and without it, all that's left is the social construct, which is what we say it is.

Many transgender people do either get, or hope to have, reassignment surgery, but many do not. Putting aside the matter of cost --- and the cost of medical care is no small thing --- pre-existing medical conditions can prevent someone from undergoing surgery, and it's not a perfect approximation of the desired genitals, and there can be surgical complications. So it's a personal choice for the transgender individual. A pre-op/non-op transgender person is the gender they declare themselves to be, simply because they declare themselves to be it.

And again, Fictional James Robinson mostly gets this right. He calls her 'she.' He says that in her mind, and his, she's a she. But then he stumbles over the "technically" line. It's frustrating.

The other objectionable element of the scene, the use of the word "tranny," is right up there with the aforementioned "trap" as the kind of word that you shouldn't use to describe a transgender person. (For the curious, terms such as transgender woman, trans woman, transgender man, trans man, trans folks, trans people, and so forth are just fine.)

Now, Fictional James Robinson is no angel and the story is pretty honest about the fact that both his character and Fictional Greg Hinkle are a mess and a pair of misanthropes, and the bordering-on-unsympathetic character is a worthy choice in fiction. The fact that there are several pages worth of Fictional James Robinson and Fictional Greg Hinkle with their Fictional Ding-Dangs flapping like freshly caught fish is a sign that James Robinson and Greg Hinkle aren't intending that flattering a portrayal.

The problem here is that when characters like these have shortcomings, they tend to work better when we, as a society, have a clearer notion of what is a shortcoming and what isn't. People overall know that you're not supposed to drink too much, that you're supposed to be loyal to someone you've sworn an oath of fidelity to, and that suicidal and self-destructive urges are not to be exalted. So when we see alcoholic, self-destructive, adulterous traits in a person, we know we're not supposed to emulate them. (There will inevitably be some outlier that doesn't get the message, but there's outliers everywhere. That's statistics for you.)

With these traits, the matters are mostly settled. With transgender issues, the matters aren't settled. The battles rage hot, even now. You can walk by a TV and hear comedians telling jokes about Caitlyn Jenner (and not using that name for her, either). The idea that transgender people are telling you the truth when they tell you what names and pronouns they go by cannot be taken for granted.

As of this writing, if a transgender person wants to get on an airplane in Canada, they have to either present as the gender they were designated as having on their birth certificate, or hand over a doctor's note describing their medical history in invasive detail. So-called "bathroom bills," restricting what bathrooms a transgender person is allowed to use, dot the political landscape of North America. (That linked one is from a bill calling itself a "transgender rights" bill. Who said irony is dead?)

This is the landscape that James Robinson and Greg Hinkle have walked into. We can't have the same level of certainty about their stances on transgender issues as we do about their stances on how good an idea mixing half a dozen drugs is. This is a cultural battle, and they've found themselves, for the moment, on the wrong side.

This is compounded by the fact that I have to draw a distinction in this article between Fictional James Robinson, Fictional Greg Hinkle, and the real versions thereof. I absolutely believe that a character can have a different perspective than the creator, since characters with differing perspectives is a basic molecule of storytelling. But the line gets blurrier with a fictionalized version of the creator. Even if, say, a stand-up comic is "playing a character" on stage, that character looks exactly like them, has their name, and is saying things that the stand-up wrote. The situation is different than if the same stand-up was playing a character with a different name, in a movie written and directed by someone else. They get judged differently, and fairly or not, their statements are attributed more directly to them.

There's merit in metafiction and semi-biographical stories blurring that line, but again: the dark side of blurring that line is that you're not sure what's on the fictional side and what's on the real side.

It's frustrating, because I can't imagine that making this statement was first and foremost in the minds of James Robinson and Greg Hinkle. Airboy touches on many more themes than just the current state of play of transgender issues in Western society.

There's the notion of being trapped by the stereotype you found yourself falling into, as Fictional James Robinson realizes that he's turned into "that Golden Age guy" without meaning it and can't find a way out of it. There's the idea of the creative as hired gun to be plugged into the reboot cycle of sprucing up old characters and selling them to the comics market with a couple of modern tweaks. There's the all-too-common fear of one's life entering a tailspin you can't pull out of. There's the idea that intellectual property only becomes worthy of reexamination when it costs next to nothing to do so. There is the gorgeous artwork of Greg Hinkle, colored in monochromes and simple, often sickly palettes that contrast with the colorful Airboy, employing stretched, tired and rubbery faces and bodies, and using mostly borderless word balloons and thin, shaky lettering. All of which conjures the scratched irises and dry throat of a morning after, with nothing but hard questions ahead.

All of these are great, and it's infuriating than rather than soar into the skies to explore these themes, James Robinson and Greg Hinkle flew straight into a tree instead.

There's been some debate about whether or not Image should pull the book. Image Comics has a long-standing reputation for creative freedom, and the debate between adhering to the company line and honoring the creator is always a worthy one in comics.

But Image Comics doesn't choose to run every single comic that's pitched its way – even simple scarcity of resources puts the lie to that. Whether intentionally or not, a comic put out by Image bears its explicit approval, even if within that approval the company gives a creative team free reign. Image should bear some of the heat for this, especially since it wasn't too long ago that the publisher had its logo done up in the colors of the pride flag.

I'm undecided about whether Image should publish the rest of the series. If James Robinson and Greg Hinkle were to tweak subsequent printings of the book, both digitally and in print, with new dialogue and art, that would be welcome.

There have been positive outcomes in this arena – writers Cameron Stewart and Brenden Fletcher famously tweaked the dialogue in the infamous Batgirl story when it was re-released in trade paperback. Creative control over your artistic statements, and the chance to definitively disown them, is important. The digital age makes this much easier to do.

But I can't help but think about that famous sign that Warner Brothers put in front of DVD collections of its Looney Tunes cartoons --- specifically, the complete set that included cartoons with racial stereotypes. The sign made it clear that the stereotypes within were disowned, and also made it clear that it was WB's stance that it would be a disservice to an honest accounting of history to pretend that these cartoons were never made.

They have a point. Revisionist history is harmful. Those who forget history, etc.

Then again, I'm white, and I'm blessed to have never had said stereotypes hit home. And there's a reason those cartoons aren't shown with the other, more timeless Looney Tunes shorts --- the racial stereotypes detract from their craft and storytelling and are just as retrograde as Warner Brothers says they are. There is a wide-ranging debate to be had here, and I'm not comfortable attempting to provide a definitive answer.

James Robinson has formally apologized, and it's worth reading. He takes ownership of his mistake and he says he's sorry for it, so this seems a sincere apology. He talks about how, down the line, he hopes to work on a project featuring a more positive portrayal of transgender people. I would welcome such a project despite how this one turned out, because the goal of social progress is measured by the growth of people. I want to see what James Robinson's learned from all of this. My shelves and longboxes groan under the weight of books with his name on them, too. I'm a fan, even if, right now, I'm a hurt fan.

In the meantime, I'm sad that yet again, another comic with transphobic portrayals has made it out in the world, and I wish that so much of writing about transgender issues in comics didn't boil down to a game of whack-a-mole against wrongheaded narratives.

Charlotte Finn is a Canadian transgender lady, Superman fanatic, and mermaid enthusiast. She tweets at @CharlotteOfOz on Twitter.

More From ComicsAlliance

![The Odds Are Stacked And The Stakes Are High In ‘Nick Fury’ #1 [Preview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Nick_Fury_1_Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![‘Black Cloud’ Goes Super Cute In Greg Hinkle’s Fried Pie Con Variant [Exclusive]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/03/Black-Cloud-Featured.png?w=980&q=75)

![Punk Is About Family: Magdalene Visaggio and Eryk Donovan Build A Better Future With ‘Quantum Teens are Go’ [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2017/01/qtag-feat.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Witchcraft, Redemption and Family Ties: James Robinson Talks Scarlet Witch [Interview]](http://townsquare.media/site/622/files/2016/10/scarletwitch-feat.jpg?w=980&q=75)