Mutant Women of Earth: How Chris Claremont Reinvented the Female Superhero

This April Brian Wood and Olivier Coipel launch a new X-Men title with a roster of Jubilee, Kitty Pryde, Psylocke, Rachel Grey, Rogue and Storm. That the team is all-female is unusual for a series that isn't defined along gender-lines. What makes the roster extraordinary is that it's an all-star line-up. These are first draft X-Men, and the book could easily have added more top picks -- Dazzler, Emma Frost, Jean Grey, Magik, Mystique -- and still been all-female.

It's hard to think of any other superhero team with such a strong bench of women, and it's especially hard to think of another team where so many female characters rose to prominence within the team itself. What these characters have in common is no mystery; they were all written by Chris Claremont, the man whose name is synonymous with "strong female characters."

"Strong female characters" is a phrase with rather a mixed reputation in comics today. Viewed retrospectively through the filter of comics' "bad girl" phase of the 1990s, which introduced a slate of violent characters whose power was only exceeded by their state of undress, it feels too much like a justification for bad behavior. Publishers could be as sleazy and exploitative as they liked so long as the character was "tough," as opposed to submissive. The concept has been ably mocked by cartoonists Carly Monardo, Kate Beaton and Meredith Gran, and reclaimed by Brennan Lee Mulligan and Molly Osterag in the webcomic Strong Female Protagonist.

Yet when used to describe Claremont's characters the phrase "strong female character" acknowledged a sincere shift in the portrayal of women away from limited, stereotypically feminine roles towards allowing women to fulfill any role in a story, up to and including carrying it.

When Claremont came on as X-Men writer with issue #94 in 1975 he inherited a series with rather old-fashioned roots. Jean Grey may be the X-Men's First Lady, but as originally conceived she was nothing special. She was a mild, vulnerable, lovestruck girl who used telekinesis to move people or objects out of the way rather than to fight her foes. While the boys faced death traps in the Danger Room, Jean's sessions involved moving books with her mind.

The X-Men launched during the golden age of the superteam. Between 1958 and 1964, DC Comics and Marvel launched the Legion of Super-Heroes, the Justice League, the Fantastic Four, the Avengers, the Doom Patrol, the X-Men and the Teen Titans. One thing these teams had in common was that they each debuted with only one woman on the roster. Even that was a step-up from teams like the original Justice Society of America and the Seven Soldiers of Victory, which didn't have any.

Jean grew in confidence and ability over X-Men's original 66-issue run -- in the final issue she held back the Hulk -- and she was even joined by a second woman, Lorna Dane (later dubbed Polaris), shortly before the end. Yet if the series had ended there, there would have been nothing remarkable about the X-Men's contribution to the depiction of women in comics.

The X-Men returned from almost five years in reprints with Giant-Sized X-Men #1 by writer Len Wein and artist Dave Cockrum. This one-shot radically reinvented the team with an international cast that included the first major black female superhero.

Storm was designed to stand out from previous super-women, and not only by dint of her race. She also had long white hair and strange oval irises, and arguably the most formidable power set in the new team. From the start, her weather-control powers allowed her to summon raging winds and lightning strikes. She was a heavyweight who had been worshiped as a goddess, and there was never any question of her using her powers only to defend or evade. She wasn't introduced as a damsel, and she wasn't introduced as a love interest.

Chris Claremont did not create or design Storm, but he put the character at the core of the X-Men throughout his epic 17-year-run, starting with his first issue (and Storm's second appearance), X-Men #94. Indeed, the only other character to have such a consistent presence during his tenure was Wolverine. These two were the only characters that readers would always follow even during their sabbaticals from the team.

Claremont also put Storm in charge of the team. She first claimed the role in 1980, but she memorably won the title from Cyclops in combat in 1986, and without her powers. In what may have been a watershed moment for the maturing genre, the contemporary black woman in the punky mohawk and leathers snatched the crown from the old school '60s boy scout in his stuffy body-sock uniform. Indeed, Storm's iconic '80s punk look was a physical manifestation of the character's complexity.

And while Claremont made Storm the X-Men's leading lady, he did not neglect her predecessor. Jean Grey was also a major project for Claremont. Though Jean initially left the team, by Claremont's eighth issue he had given her a major power boost and laid the groundwork for one of the biggest stories in superhero comics history. In X-Men #101, Marvel Girl became Phoenix. In X-Men #129-138, Phoenix became Dark Phoenix.

"The Dark Phoenix Saga" was an ambitious story about power and sacrifice, and it had a woman -- the X-Men's original vulnerable girl -- at the center of it. Though the story did not end well for Jean, her sacrifice gave the story its substance. Claremont took the archetypal team girl and made her the star of one of the most important works in superhero fiction.

The team introduced in Giant-Sized X-Men #1 was actually less balanced than the original one-in-five team -- just one woman in a team of eight -- and though Claremont tweaked the numbers by writing out Sunfire, Thunderbird, and eventually Banshee, and by giving Jean an on-and-off spot on the team, the death of Jean Grey would have once again given the X-Men one woman on a team of five. Fortunately, Claremont had a plan. In the very first issue of "The Dark Phoenix Saga," Claremont introduced a new character who would serve as Jean's de facto replacement.

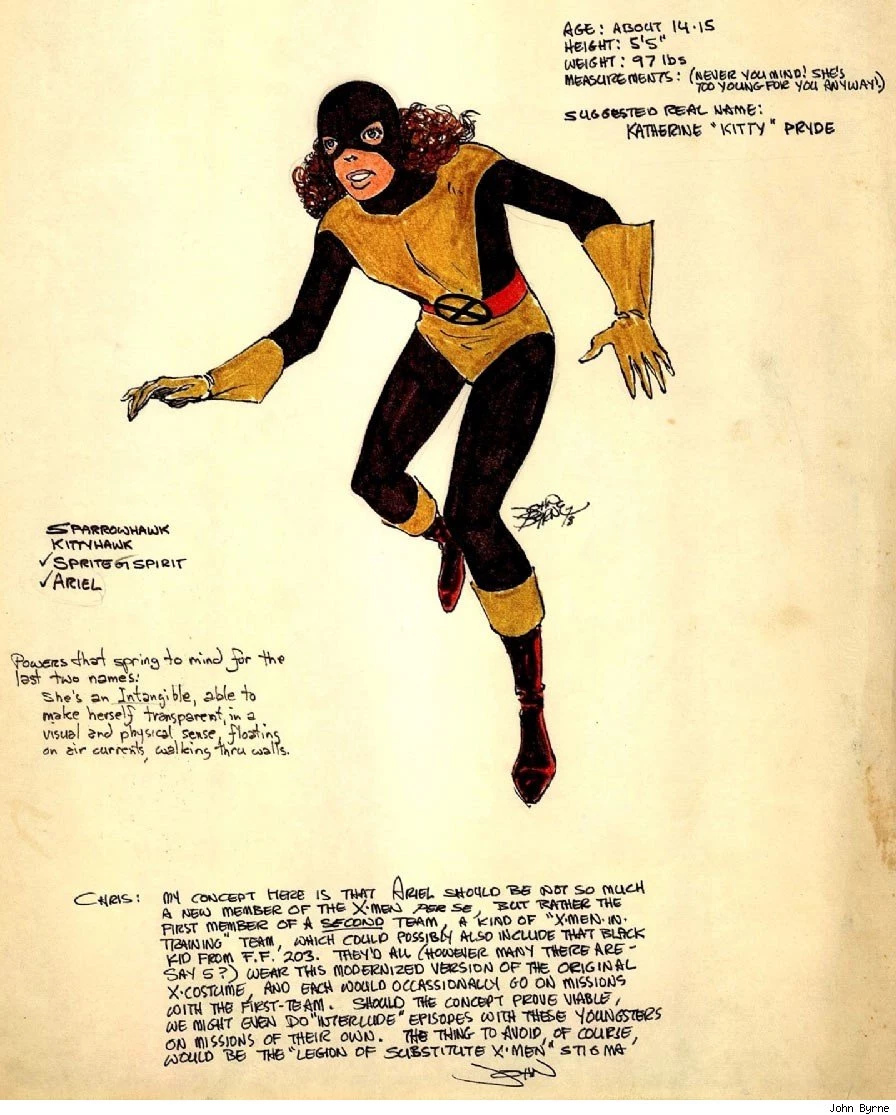

Kitty Pryde was the first new hero Chris Claremont and artist John Byrne created for the X-Men. She made her début in X-Men #129 in January 1980, in the same issue that introduced Emma Frost, just one issue before the début of Dazzler. Kitty's arrival was radical. Although Kitty could be seen as a throwback to Jean's original role as the teen ingénue with defensive powers, she served a different purpose. She was an observer, a kid in a world of adults, and that made her the audience identification character and the center of the series. Readers were reintroduced to the X-Men through her eyes, and even her romance with Colossus was more about her experience than his.

By making his first new X-Man a girl, Claremont established a team of four men and two women. He also set a precedent that he would follow for much of his run. Kitty was the first of five women Claremont added to the team over the course of seven years. (The only male character added during the same period was Magneto, who served as Xavier's replacement as headmaster.)

Rogue, created by Claremont and Michael Golden in 1981, joined the team in 1983, giving the team four men and three women. Rachel Summers (later Grey), created by Claremont, Byrne and John Romita, Jr. and introduced in "Days of Future Past" in 1981, became the fourth woman on the team when she joined in 1985, albeit for a tenure of barely more than a year.

Psylocke, created by Claremont and Herb Trimpe way back in 1976, joined the team in 1986, effectively replacing the injured Kitty. And Dazzler, originally conceived as a multimedia project in partnership with a record label, joined the X-Men in 1987, bringing the team back up to four women. Longshot joined the team near-simultaneously, creating the gender-balanced roster of four men and four women that endured through most of Claremont's "Australia era."

None of these women were the hero's girlfriends. None of them were the designated damsels. None of them were weak or meek, and none of them were derivative versions of male characters (a trope that the X-Men has mostly avoided with the exceptions of X-23, Lady Mastermind and Polaris). Each woman had a different story to tell, and none of them could have stood in place of any of the others. Rogue was a wayward teen dealing with isolation and anger. Rachel was an abuse victim lashing out at the world. Dazzler was a former star perennially trying to recover her identity out of the spotlight. Psylocke sought to reconcile her inner toughness with her outer frailty.

Psylocke's storyline made some sense of her eventual emergence as a '90s bad girl, though the result was still transparently exploitative. There was often a sexual element to Claremont's portrayal of women, and Psylocke's Jim Lee-designed ninja swimsuit was one manifestation of it. Rachel's studded red leather bodysuit and the Hellfire Club's corsets, crops and thongs were even more obvious evocations of Claremont's thematic interest in sado-masochism and subjugation.

Yet there was complexity to Claremont's approach to sexuality; his women were not all of one sexual type, and they did not represent one experience. Virginity meant something quite different for Kitty and for Rogue. Psylocke was determined to claim ownership of her body. Storm was as liberated as any of the libertine villains that the X-Men went up against. Emma Frost even argued, in a Classic X-Men #128 vignette by Claremont and John Bolton, that her style of dress was a form of personal empowerment.

Claremont's interest in female characters was obviously the work of a man with a sexual interest in women. That doesn't diminish his contributions as a writer of female characters. If his primary interest was prurience he would only need one woman on the page (or maybe two).

Claremont not only substantially swelled the ranks of Marvel's female heroes, he also filled his supporting cast with characters like Moira MacTaggart, Lilandra Neramani, Stevie Hunter, Jessica Drew, Carol Danvers, Callisto and Maddy Pryor, and he continued his commitment to female characters in his other mutant team books. In 1982, Claremont and Bob McLeod established the New Mutants, a new class of teen mutants with an initial cast of two men -- Sunspot and Cannonball -- and three women -- Karma, Wolsfbane and Mirage. He added one boy, Cypher, one ostensibly male alien robot, Warlock, and two more girls, Magik and Magma. Under Claremont, the New Mutants was dominated by its women.

In 1987 Claremont created Excalibur with Alan Davis; another team of two men -- Captain Britain and Nightcrawler -- and three women -- Kitty, Rachel and Meggan. The friendship between Rachel and Kitty was the core of the book.

Claremont left the X-Men books in 1991, but not before adding one more woman to the team. Ten years after Kitty Pryde was his first recruit, another teen girl with a very different attitude became the last of his original run. Jubilation Lee was not a quiet observer with passive powers. As brash and obnoxious as the decade that followed, she hitched her wagon to Wolverine and threw herself into trouble. Claremont wrote Jubilee for less than two-dozen issues, but he made sure readers knew who she was, and she was again very different in character to all the women who came before her.

After Claremont, things changed. New Mutants became the ultra-macho X-Force, and the next four new female characters added to the X-Men were Revanche, Cecilia Reyes, Marrow and Stacy-X. None of them made an indelible mark. Other new members were graduates or transfers from other corners of the X-Men's world, many of them Claremont creations; Moonstar, Sage, Emma Frost, Mystique, Magik, Hepzibah, Karma. Claremont's own return to the X-Men in 2001 introduced new characters like Lifeguard, Lady Mastermind and Omega Sentinel, but the seeds of these characters were planted in less fertile ground.

And yet the X-Men still have a reputation for strong female characters more than two decades after the end of Claremont's initial run, and for a generation of creators brought up loving Claremont's stories the idea of creating a classroom of characters where men outnumber women four-to-one should seem inconceivable. The waves of new students at the Westchester School in the last 13 years have borne that out, and characters like Pixie, Armor, Dust, X-23, Hope, Idie and Warbird have emerged as the potential next generation of X-Men stars.

They have some work to do to become as fundamental to the X-Men as Claremont's "strong female characters." Storm and Kitty Pryde are not the X-Men's equivalent of Scarlet Witch and Wasp. They're the X-Men's equivalent of Captain America and Iron Man. (Cyclops is the X-Men's Wasp, and also the X-Men's WASP.) Claremont's work on these characters, and on Jean Grey and Emma Frost, on Dazzler, Rogue, and Psylocke, on Rachel Summers, Dani Moonstar, Magik and Jubilee, are the very foundation of the modern X-Men. Because Claremont made these characters complex and compelling, and because he did not limit the sort of stories they could be used to tell, the women of the X-Men are the X-Men.

Before Claremont, female superheroes were typified by Jean Grey. After Claremont, female superheroes could be the Phoenix. Female superheroes could be anything.

More From ComicsAlliance