The Double-Batmen of ‘Batman, Inc.': What Does It Mean for the Dark Knight?

This week, The Source confirmed something that many of us have suspected for a while now: When Bruce Wayne makes his return this November, he and Dick Grayson will both be operating as Batman, with Dick seeing action in the pages of "Detective Comics," "Batman" and "Batman and Robin," while Bruce (or "Batman Classic," as I like to call him) will be setting up shop in the new titles, Grant Morrison and Yanick Paquette's "Batman, Inc." and David Finch's supernatural-themed "Batman: the Dark Knight."

That's right, folks: After seventy years, we have finally achieved Double Batman. But what does it mean?

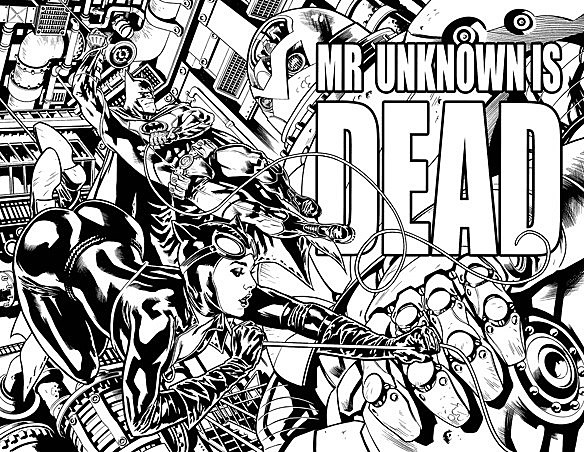

Well, aside from the fact that Yanick Paquette's artwork is absolutely gorgeous -- as evidenced by the preview page above, which looks like an amazing mash-up of Kevin Nowlan and Adam Hughes -- the fact that Bruce Wayne is franchising his Batman brand could have some pretty huge ramifications for the character.

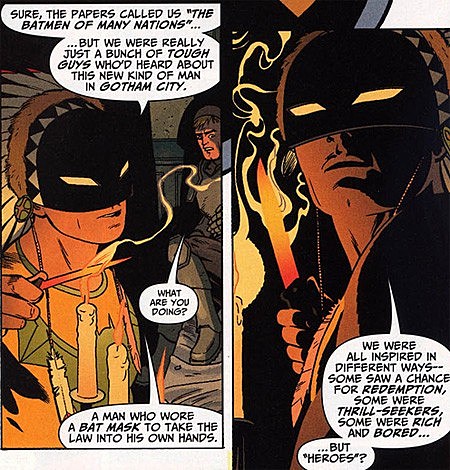

Throughout Morrison's run, there's been a sharp focus on Bruce Wayne, dealing with his past ("Batman and Son"), the elements that set him apart from others who would do the same thing ("The Black Glove") and the preparations that he's made as an individual to counteract even the most dangerous threats. But there's also been a parallel narrative that's been building on the legacy that Bruce Wayne has created: "Batman and Son" introduces Damian Wayne, who we see in "Batman" #666 carrying on his father's work in the future; "The Black Glove" reintroduced the Club of Heroes, who were inspired by Batman to become heroes themselves; and "Batman R.I.P." is entirely predicated on the fact that if you take Bruce Wayne out of the equation -- if you ruin his mind, dose him with drugs and kick him out on the street -- the Batman will endure.

It's important to note that this isn't just a matter of two people being dressed as Batman. That, we've seen before, and Morrison's even dealt with it himself in the story about the three policemen who are trained to be "replacement Batmen," and who all three meet tragic ends, buckling under the pressure that forged Bruce Wayne into something else, and I think that's the key factor of what's going on in this story.

Every other story abut a Replacement Batman, whether it's something as big as Azrael or as small as Tommy Carma, a disturbed ex-cop who snapped after the death of his wife and daughter and took on Batman's identity for two issues in 1987, have all ended more or less the same way:

Bruce Wayne displays his superior Batmanness and reclaims what is essentially his, the identity of the One True Batman.

When you get right down to it, these guys were never actually Batman, they were just guys in Batman costumes. And I think what sets Dick Grayson apart is something that Morrison's been getting at throughout his run: That it's Batman himself who makes the difference. The replacement Batmen are subjected to horrible tragedy in their past, either by chance or through the machinations of Dr. Hurt, who (like the Joker) believes that to be the essential ingredient for making Batman:

But with them, it doesn't work. Tragedy is the essential ingredient for making Batman out of Bruce Wayne, but what sets Dick Grayson, Batwoman and the Club of Heroes apart from their more sinister counterparts is that they get the ingredient necessary to make Batman out of someone else: the direct inspiration of Batman Himself.

Dick Grayson has a tragedy in his past very similar to Bruce Wayne's: His parents are murdered by criminals in front of him. He even has an advantage over Bruce, since when they die, he's already trained to be an acrobat and athlete. But as Morrison shows in "Last Rites," without Batman already in place, Dick Grayson wouldn't have become a hero; he would've become a victim:

And it's not limited to Morrison stories, either: Under Greg Rucka and JH Williams, Batwoman is shown to be a character who was denied her chance at putting her drive and desire for justice to work in a conventional way (in her case, by joining the Army), but was inspired to become a super-hero instead, adhering to Batman's code (as she says in "Detective" #857, "I'm always on the Batman rule, sir") as closely as she did the Military Code of Justice. It's the literalization of the idea that Batman exists to keep people from becoming victims, and in the process, he turns them into heroes.

It's a similar theme to one that Alan Brennert and Dick Giordano explore in "To Kill a Legend" (from "Detective Comics" #500), which is unquestionably one of the best Batman stories of all time. In it, the Phantom Stranger takes Batman to a parallel world on the night where that world's Thomas and Martha Wayne are going to be murdered -- inspiring that world's Bruce Wayne to become Batman -- and gives him the choice to save them and prevent his personal tragedy, but at the risk of losing all the good that comes from the existence of Batman.

Batman saves the Waynes, of course, because the one unshakable idea at his core is that Batman doesn't let anyone get hurt by crime if he can do anything in his power to prevent it. No matter what the consequences are for tomorrow, his is a fight that exists today. The twist, though, is that after being saved by "the bat-winged creature that swooped down from the sky, saving the lives of himself and his family," the Bruce Wayne of that world dedicates his life to becoming Batman himself:

The very existence of Batman perpetuates itself. The fact that Bruce Wayne puts on that costume and fights against crime changes everything. It's the other side of the argument that Batman creates his own villains -- he also creates his own allies. He inspires others in the same way that he himself was inspired, but does so by removing tragedy and replacing it with an ideal. Batman turns tragedy into justice, not just by punching out criminals, but by giving people something to believe in and aspire to.

This is an that sits at the very core of modern Batman stories, especially in both Morrison's work and in Christopher Nolan's film, "The Dark Knight," that "Batman" is something more than a man, that it's an ideal that Bruce Wayne has devoted (and in a lot of ways, sacrificed) himself to. And if that's true, if "Batman" is a symbol that's bigger than one man could ever be on his own, then there's nothing to stop other people from taking that aspect onto themselves, which is exactly what happens when Batman is sent back in time:

When Boy says "I followed you," he's not just talking about how he physically tailed Bruce Wayne to his current location, he's talking about following him -- changing himself to suit these ideals, adopting Batman's ways and symbols as his own. And in doing so, he creates the Miagani, the Bat-People, who are the focal point of "The Return of Bruce Wayne" as the first example of Batman "franchising," 15,000 years before his parents die in Crime Alley.

This is the start of a legacy that, as Morrison shows in "Batman" #700, continues through Dick Grayson and Damian Wayne to Terry McGinnis and on into the future -- it takes away Bruce Wayne's identity as the "one true Batman," and instead casts him as the originator whose actions changed everything.

Even more than Bruce, though, it marks a pretty massive change for Dick Grayson.

Throughout the run of "Batman and Robin," the crux of Dick Grayson's arc as a character has been that he doesn't want to be Batman, and that he's merely playing a role until Bruce returns. "I'm not Batman" has, in fact, been the core of his character ever since he originally ditched his Robin identity back in the '80s -- in favor, ironically, of a super-hero name handed down by Superman.

The whole idea is that this is something he never wanted to own up to -- his "worst, worst nightmare" according to "Batman and Robin" #1 -- but that it was inevitable. But just as inevitable in the world of super-hero comics was Bruce Wayne's return, and Dick's role in that has been indicative of nothing so much as the trust and dependence that exists between the two:

Even while wearing the Batman costume himself, Dick still sees himself in terms of his relationship with Bruce. He doesn't want to take this Batman identity because it means that Bruce is gone, and he's wants nothing more than to change that fact. He'll be Batman as long as he needs to be, but his ultimate goal is to remove that need entirely:

With Bruce's return, though, he's no longer wearing a dead man's clothes, and rather than return to -- let's be honest here -- the minor leagues as Nightwing, it looks like he's going to be operating not as a sidekick, but as someone equal in every respect, right down to the name. He's going to be Batman, just as Bruce is Batman -- the Batman created by tragedy and the Batman created by Batman.

It's a mathematical certainty that this isn't going to stay this way forever, but regardless, it's very, very interesting to see DC take a different approach to the Batman legacy, if only for a short time. With a traditional legacy like the Atom, which recently saw Ray Palmer return and thus Ryan Choi get brutally murdered in order to make room, there's a limit of one character at a time. Even when Wally West and Jay Garrick were both operating under the name "The Flash," there was no doubt left in the reader's minds as to who was really the fastest man alive -- mostly because Mark Waid wrote Wally applying that epithet to himself in pretty much every issue. With the "franchising" of the Batman identity, however, it's become something more like what they do with Green Lantern: Multiple characters operating under the same identity, even if we all have to agree that Hal Jordan is the most bestest one ever.

More than anything else, it subverts the expectations that come along with a character returning to claim his identity, especially when you consider that it's Dick Grayson, not Bruce Wayne, who's going to be operating in the long-running "core" titles, including the one just called "Batman." It gives him a legitimacy that, at least for now, signifies a pretty drastic change in how both characters work.

More From ComicsAlliance