Ask Chris #114: ‘The Dark Knight Returns’

Over a lifetime of reading comics, Senior Writer Chris Sims has developed an inexhaustible arsenal of facts and opinions. That's why each and every week, we turn to you, to put his comics culture knowledge to the test as he responds to your reader questions!

Q: So you've talked a lot about Batman, but I haven't heard much from you about Miller's Dark Knight Returns. Is DKR awful or great? Parody or serious? Is its vision of Superman atrocious or a reflection of Batman's paranoia? -- @Poormojo

A: I have to say, you are probably the only person in my entire life who has claimed to not hear enough from me about The Dark Knight Returns. Usually, people have trouble getting me to shut up about it. But, since this seems like a pretty good week to talk about "final" Batman stories, let's get to it! Unsurprisingly, DKR is one of my all-time favorites, although I'll admit that it seems like the older I get, the less I like it. There are a lot of factors leading to that, not the least of which is the fact that I've read it over and over and over again since I picked up the 10th Anniversary paperback when I was 14, and that kind of familiarity tends to dull the edge, especially when you're chasing the thrills that came along with something you first experienced as a kid. But there are others, too, like Miller's return for an underwhelming sequel -- which certain Davids here at ComicsAlliance will defend to the death -- but the worst offender has always been imitation.

Unsurprisingly, DKR is one of my all-time favorites, although I'll admit that it seems like the older I get, the less I like it. There are a lot of factors leading to that, not the least of which is the fact that I've read it over and over and over again since I picked up the 10th Anniversary paperback when I was 14, and that kind of familiarity tends to dull the edge, especially when you're chasing the thrills that came along with something you first experienced as a kid. But there are others, too, like Miller's return for an underwhelming sequel -- which certain Davids here at ComicsAlliance will defend to the death -- but the worst offender has always been imitation.

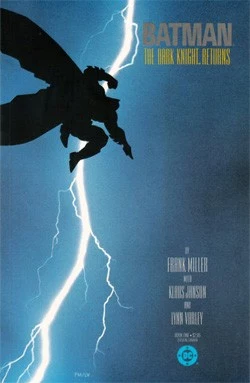

I still hold DKR itself as a masterpiece, but the themes and imagery that Frank Miller, along with Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley, used to such great effect in their four issues have essentially become a building block for virtually everything that came after. It changed the character forever, in the way that the best comics tend to do, influencing everything from the way Batman interacted with other characters to the way he looked. And in the process, as much as I hate to say it, there are a lot of ways that it kind of ruined Batman.

See, here's the thing about DKR: A lot of people see it as a companion piece to Miller's other groundbreaking work with the character (alongside the incredible David Mazzucchelli), Year One. They view them as the Alpha and Omega of Batman stories, a beginning and an ending that every other Batman story can (and must) fall between. David Brothers even wrote a very compelling piece about this idea, and even managed to fit All Star Batman & Robin in there somehow, and at first glance, it all really makes sense. But, at least in the way I look at things, that's only half right.

Year One and The Dark Knight Returns are bookends, but not to each other. They're in the other order: DKR is the ending of everything that came before it, and Year One is the start of something new, the version of Batman that we have today.

It's almost exactly the same setup that you get from Alan Moore and Curt Swan's Whatever Happened To The Man of Tomorrow clearing away the Silver Age so that John Byrne can start fresh with Man of Steel, except that Miller orchestrated it all himself. The publication dates even match up, with DKR being released first, kicking off during Crisis in early 1986, with Year One debuting in Batman the following year. That's part of the key to really understanding DKR.

And that's why I made the comment about DKR "ruining Batman." When you look at them in that order, you can see the folly in trying to match them up as one single, overarching framework for Batman. Even though there's some thematic carryover, like Sarah Essen showing up in DKR and then being "introduced" as a love interest for Gordon in Year One, it just doesn't work. Despite that, there was a wave of stories that followed focused on progressing Batman ever closer to the hulking brute that we see in DKR, hammering him to fit into a series of diminishing returns meant to echo that groundbreaking series and, I'm sure, its sales. The most notable offender is Jim Starlin and Bernie Wrightson's the Cult, which goes to truly hilarious extremes that involve modifying the Batmobile into a monster truck that's a little closer to DKR's Bat-Tank and then justifying it by creating the riots that Miller mentions in an off-hand line, but it's far from the only one. It's a meme in those books that continues even today, and it can even be done well, like the implication at the end of Scott Snyder's run on Detective Comics that the actions of James Gordon Jr. (an often-overlooked piece of Year One) will result in the rise of the Mutant Gang from DKR. It's something that's been ingrained over and over into the franchise over the past 25 years.

But it doesn't really work, because what makes DKR great isn't that it's a logical progression. It's the opposite, and that's the other part of understanding the story. It's meant to be a contrast. And specifically, it's meant to be a contrast to this:

Maybe not the television show specifically, but certainly that era of Batman. Miller says as much in his introduction to the 10th Anniversary edition, and it's really the Rosetta Stone that lets everything fall into place. DKR isn't just about Cranky Old Batman coming out of retirement and being Batman again, it's about Batman coming out of retirement and being very, very different than what we know.

Just look at the first things he does when he comes back: He throws batarangs that stab into his enemies arms instead of conking them upside the head, and kicks a dude in the spine so hard that he'll only "probably" walk again:

It's brutal stuff, and it's exciting -- and the reason that it's exciting is that it's different, especially if the image of Batman that you have in your head is the bright, cheery, non-spine-injuring Batman of the '66 show. That shock, that contrast, is what sets the tone for the story, that we're seeing a Batman and a Gotham City that have changed.

There's a reason that when Bruce Wayne finally puts on his costume and comes out of retirement, it's this costume, the bright, blue-and-grey suit with the bulky utility belt that'd be right at home around Adam West's waist...

...and why Batman eventually works his way backwards into the darker, sans-oval black-and-grey costume that evokes the more ruthless, Shadow-esque early stories of the Golden Age.

I've talked before about how the idea behind Batman is very much a child's fantasy, and one of the things that makes DKR such a good read (beyond just being a great comic produced by creators at the top of their game) is how Miller explores the idea of what happens to that childhood fantasy once you've grown up and the answers aren't quite so simple. At the start of DKR, Bruce Wayne isn't just retired from crimefighting, he's actually a failure. For all the sacrifices that he made during his years as Batman, he didn't really end up making anything better -- and in fact, things in Gotham City are actually worse than they used to be, with roving gangs of sociopathic murderers dropping bombs into mothers' purses replacing the outlandish heists and thematic robberies that he, and we as readers, viewers and fans, are used to.

There's a hopelessness at the core of DKR, but it's a hopelessness that's very compelling, and that's defeated in a very optimistic way. There's something we can all identify with in the idea that the things you did as a child -- like, say, swearing to make war against all crime and evil-doers -- are silly and ultimately pointless, but that there's still a core of truth an nobility to them. As the story goes on, it's revealed that the solution to Batman's problem wasn't to give up on those childish fantasies and stop being Batman because he grew up, but to keep going and spread those dreams to others. Boiled down to a purely symbolic level, it's essentially a book about how it's okay to still really like Batman when you're about to turn 30, like Frank Miller was when he wrote it and like I am as I write this.

Looking at it that way, you can even forgive the pretty atrocious characterization of Superman. That's something else I've written about before, how frustrating it is to see Superman reduced to a mindless government stooge, but symbolically, it works. Superman represents authority, the kind that's approved by grown-ups as a role model, and the kind that you have to rebel against if you're going to make your own way. Their entire battle at the end of the book is beautiful in how much symbolism Miller works in there -- it was only a few years ago, around my four hundredth read-through, that I realized what it meant that Batman was literally hitting Superman with the entirety of Gotham City when he plugged into the lamppost.

That, incidentally, is another thing that DKR ruined about Batman: Everyone wants to recapture the feeling of that scene, but nobody's even come close to building something so meaningful, something that felt so fresh, because we'd already seen it here first. Instead, it's just one pale imitation (lookin' at you here, Hush) heaped onto a pile until it all feels cheapened. Believe me, I never, ever need to see those guys fight again, unless it's Superman casually backhanding Batman through a mountain.

Anyway, even characterizing it as an "ending" to Batman doesn't quite do the story justice. It ends with Batman rebuilding his legacy, continuing on, going back to that never-ending battle. It's extremely optimistic -- far more so than the end of Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow, an interesting inversion of how those two characters tend to be categorized. That's what makes it such a great "ending," that it's not one, because these stories never really end.

Instead, they just begin again, which is where Year One comes in. We see what happens to Silver Age Batman, closing out his career with a reminder that he'll always be out there fighting against evil, and then we get the setup of something new. The entire point is to leave it open-ended, and compared to DKR, the Batman of Year One is surprisingly mellow. There's an incredible contrast between DKR's first outing as Batman, marked by thuggish brutality, and the first strike we see in Year One, where Batman ends up having to drop his tough-guy persona to keep from accidentally killing the criminals he ambushes on the fire escape. There's a softness there, a return, however mixed it may be with the overt violence of Batman, to the childish idea at the core. He wants to fight crime without actually killing anyone.

Needless to say at this point, I've thought about The Dark Knight Returns a lot. For me, that's how it all fits together. Of course, I also consider to be DK2 to be fan-fiction, so take that as you will.

More From ComicsAlliance